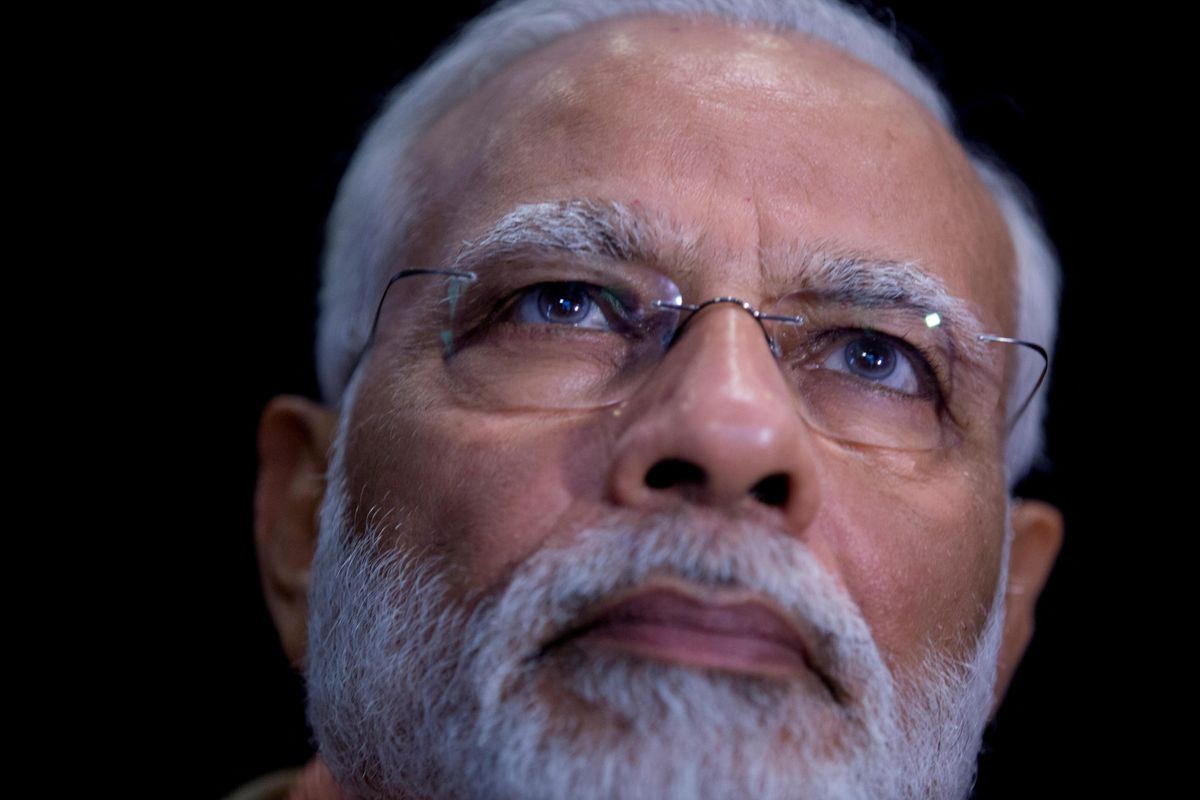

Narendra Modi’s political juggernaut seems unstoppable.

Through a series of maneuvers — some of them questionable, if not illegal — Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP party last week took the reins of Maharashtra, India’s richest state. It was yet another victory for Modi in the run-up to elections in 2024, when he is expected to secure a third term.

But Modi’s take-no-prisoners style of governance, coupled with a weak opposition, a compliant judiciary, a supine press, and a society struggling with weakened civil liberties, is increasingly threatening the pillars of the world’s largest democracy.

What happened: The BJP regained its foothold in Maharashtra, home to Mumbai, by allying with about 40 “rebel” lawmakers who broke away from the state government of another right-wing party, the Shiv Sena. Though long deemed as a natural ally to the BJP, Shiv Sena’s leader, Uddhav Thackeray, had led a “secular” coalition that included opposition parties unaligned with Modi’s brand of Hindu supremacy.

Thackeray’s progressive moves triggered a schism within his ranks, which Modi then exploited.

“[The] BJP under Modi used the combination of ideology and realpolitik to bring down the existing coalition government” led by Thackeray, says Ashutosh Varshney, director of the Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University. Thackeray’s crime? He “was moderating Hindu nationalism” and running “India's most financially powerful city in a way that was hurting the BJP.”

The stakes:Smashing the coalition run by Thackeray — a conservative, albeit more moderate than Modi — took a few weeks. But the BJP is now back in control in the state where most of India’s business is conducted, making no apologies for fracturing a former ally’s ranks with Machiavellian precision.

Also, Maharashtra is a political trophy.

Its state capital, Mumbai, is the 20-million-strong financial and cultural hub that’s home to Bollywood. Maharashtra is also India’s second-most populous state and has drawn almost a third of all foreign direct investment to the country since 2018. It’s responsible for a fifth of India's sales tax revenue, and the single-largest contributor to GDP. Finally, Maharashtra accounts for nearly one-tenth of MPs in the lower house of parliament.

In short, Maharashtra has what every Indian politician wants: votes, money, and Bollywood dreams.

What this means for Indian politics: The BJP now is directly governing or partnered to rule 18 of India’s 28 states, including Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Bihar. With the opposition Congress party — which ruled India for much of its 75 years since independence — essentially dead in the water with a leadership crisis, it is regional parties that pose the main threat to the BJP. Shiv Sena was one such threat, which is why Modi took aim.

This targeting will continue because “the regional parties are the most important opposition today to the BJP,” says Varshney. Governance, he says, is less important than ideology for Modi. Despite ruling Maharashtra well during the pandemic and even experimenting with environmental policies, Shiv Sena was singled out because it was not “ideologically pure enough” for the even more Hindu nationalist BJP.

Shiv Sena’s fracturing will now serve as a template Modi can use against other regional players who pose a threat to his leadership, Varshney adds.

Rapid growth, but with rising inequality and intolerance: Boasting the world’s fastest economic growth rate, there is no doubt that India is doing well. Last month, it reached the $3.3 trillion mark, surpassing the UK as the world’s fifth-largest economy. But as Indian billionaires rise up, exports boom, and stock markets surge, so do joblessness and inequality.

The same parallel can be drawn to India’s polity. Modi’s BJP used scorched-earth tactics to get elected in 2014 and 2018. His hard-nosed campaigning, combined with cutting-edge PR, helped the BJP secure votes. However, while the party grows electorally, it does so not just at the expense of the opposition — but also by undermining India’s progressive democratic values.

Recent examples of targeting civil society, muzzling the press, even persecuting Bollywood stars suggest that if you investigate Modi or fail to fall in line with his communal politics, you’re out. These tactics also show that the Indian judiciary — with a proud history of checking executive authority — is increasingly compliant with Delhi, according to Varshney. This threatens the secular ethos of the Indian republic and its constitution, especially as Modi looks poised for a third term.

“It is a very, very difficult moment for the polity,” says Varhsney. The 1950 constitution, which guarantees rights for all, “will come undone if Modi wins in 2024,” he predicts. While there are no constitutional grounds upon which he can declare India a Hindu state, Modi is transforming India into a de-facto one, Varshney argues.

“India will not come undone with another Modi victory,” says Varshney. “India will just become a very different place.”

The coup in Maharashtra and the latest crackdown against his critics were conducted while Modi was in Europe last week, hobnobbing with the global elite at the G7 summit in Germany. India isn’t a G7 member, but Modi was there because India is increasingly important for the West’s grand plans, especially the role it could play in checking the rise of their common strategic rival, China. But amid all the jet setting and handshakes, G7 leaders — all democratic countries — must understand the stakes of betting on Modi.

He might play their game, as he does his own thing at home, but it will be at the larger expense of democracy’s most sacred ideals.