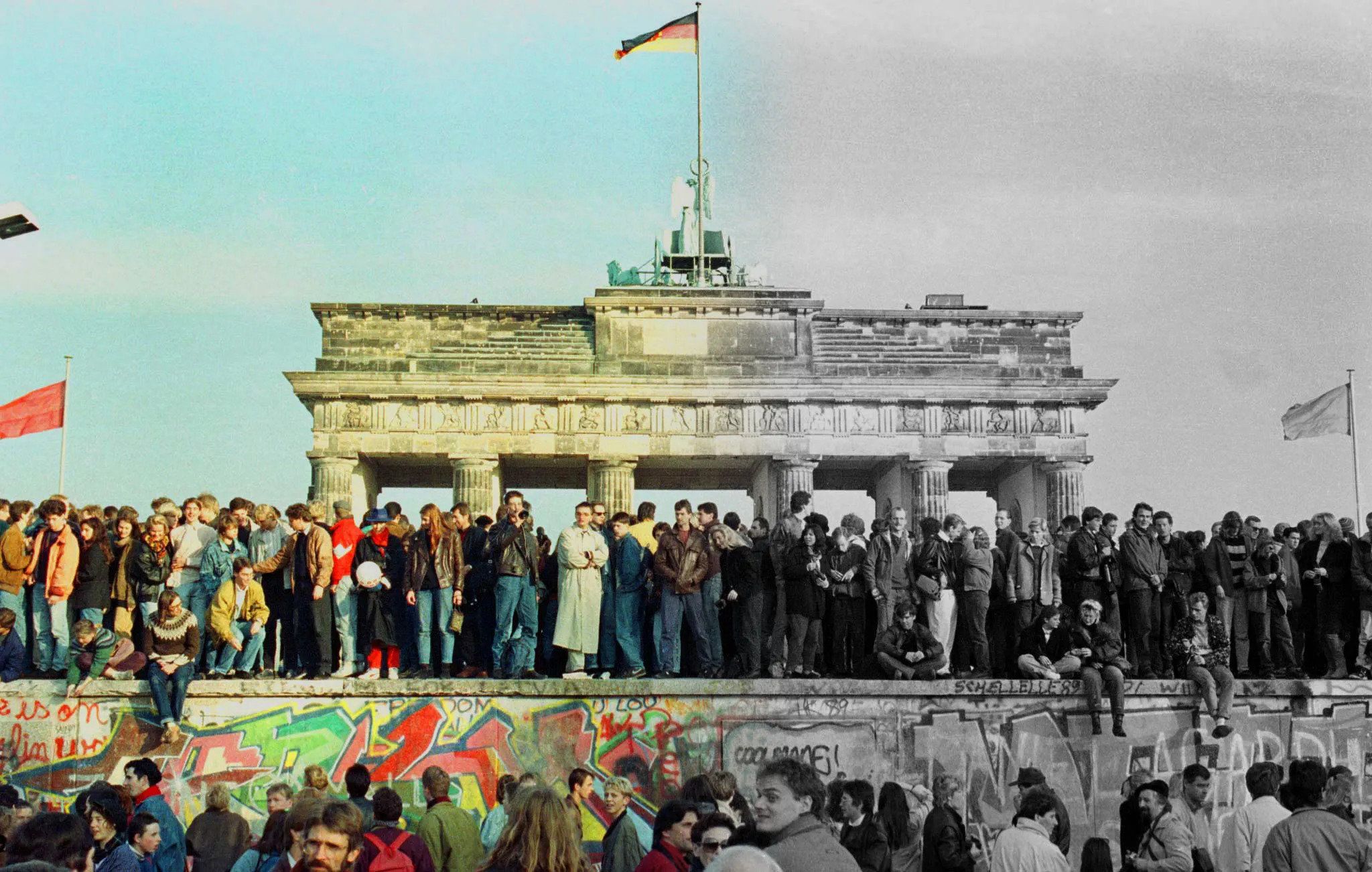

Though celebrations will surely be more subdued this year, many Germans will still gather (virtually) on October 3 to celebrate thirty years since reunification.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall — and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union — Germany reunited in a process whereby the much wealthier West absorbed the East, with the aim of expanding individual freedoms and economic equality to all Germans.

But thirty years later, this project has — to a large extent — been difficult to pull off. The economic and quality of life gap is shrinking, but lingering inequality continues to impact both German society and politics.

Wealth gap. Though much progress has been made in expanding economic prosperity in the post-unification era, former West Germany generally remains wealthier than the former East. Research shows that Eastern states continue to lag behind on unemployment and productivity.

Indeed, a 2019 government report on the "status of German unity" (2018 report in English can be read here) confirms that wage earners in the East generally earn less, while their risk of falling into poverty is about 25 percent higher. (It's worth noting that excluding Berlin, 12.5 million people live in the former East, while more than 66 million Germans live in the former West.)

Lack of opportunity breeds resentment. Inequality and lack of opportunity have created a sentiment of disillusionment among many East Germans who feel less optimistic about their financial prospects and ability to thrive. A recent Pew poll found that 42 percent of East Germans say that their children will be better off financially than they themselves were, compared to 50 percent of West Germans who said the same.

Indeed, in recent years, many East Germans have expressed resentment at having not reaped the rewards of reunification, which, in turn, has given renewed emphasis to identity politics within that part of the country.

Far-right support surges in the East. The unequal state of play has led many East Germans to pin their hopes on far-right political parties — like the populist Alternative for Germany (AfD), the largest opposition party in the Bundestag, — that seek to exploit public disgruntlement over the economic challenges many have endured in recent years to expand their political cause.

And it's working. For years, the far right has been gaining steam in the former East. For example, in state elections held last year in Thuringia, the AfD won 23 percent of the vote, up 13 points from 2014. The far right's illiberal and anti-immigrant views also resonated with economically disadvantaged voters in places like Saxony and Lusatia, helping the AfD secure several victories across the former East.

Education: an equalizing force? While East Germans tend to be less optimistic than West Germans about the education system, analysis shows that schools in most eastern states outperform students at West German institutions in areas like math, biology, and chemistry.

Chancellor Angela Merkel, Germany's long-serving leader and a former scientist is herself a symbol of what has been achieved by reunification: Growing up in the former East — where her family had to dodge the Stasi (secret police) — Merkel rose through the ranks to become one of Germany's — and Europe's —most consequential leaders.

Looking ahead. Chancellor Merkel and her centrist coalition received a boost in the polls in recent months, buoyed by widespread approval of her government's handling of the coronavirus pandemic. But if a "second wave" comes in the winter, and unemployment rises, the AfD may get a new opening to exploit that discontent to exacerbate existing East-West divides.