Countries that rely heavily on imported food and energy face the greatest risk of social and economic crises from the disruption caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet even those that are themselves big producers of these essential commodities are suffering fallout from the war. Rising prices for basic goods in many parts of Latin America, for example, are testing governments already struggling to manage elevated public frustration caused by pandemic hardships. We asked Eurasia Group expert Yael Sternberg to explain how this is playing out.

What has the initial impact been in the region?

Though countries such as Brazil and Colombia are large food producers, they are now having difficulties obtaining the Russian and Ukrainian fertilizers they have come to rely on. Similarly, though the region has large reserves of crude oil, it obtains much of its supply of diesel, gasoline, and other fuels from European refineries. As these companies shun Russian oil, they have less diesel and gasoline to sell to Latin America. Argentina is already suffering from an acute shortage of diesel, an essential fuel in the transportation and agricultural industries. The same problem is looming for Brazil.

What will the economic and political consequences be?

Latin America is still reeling from the economic hit of the pandemic, which exacerbated inequalities and fueled rapid inflation. The fallout from the Ukraine crisis is ratcheting up inflationary pressures again as higher prices for fertilizers and fuels drive up the cost of food and other goods. Wary of unrest, leaders are offering subsidies for many of these items despite already strained state finances. Many are also backtracking on plans to rein in pandemic-era stimulus programs. Chile and El Salvador have both announced new support plans in recent weeks that include subsidies and tax breaks. The Chilean administration was able to integrate its plan into the framework of its already approved 2022 budget. But El Salvador, which already plans on using a controversial funding strategy of issuing bonds denominated in Bitcoin, will face more difficulties financing the new spending.

Has there been unrest?

Yes. Argentina and Peru have both experienced significant bouts of unrest. Activists camped out recently on Buenos Aires’s main avenue to demand greater social spending, and Argentine truckers led a nationwide strike in response to rising diesel prices. Peru has erupted in even more violent demonstrations across the country over rising inflation, prompting President Pedro Castillo to impose a 24-hour curfew in the capital city of Lima only to revoke it hours later, further evidencing his erratic policymaking tendencies and lack of experience. The crisis comes at a bad time for Castillo, who is struggling to hold on to power after two impeachment attempts.

Is there a silver lining in the rising prices for the commodities the region produces?

Latin America is a big exporter of agricultural goods, oil and many metals, so higher international prices for these items will buoy local producers and generate more tax revenue for governments. Ecuador, for example, has benefited from higher oil revenue. Yet, as mentioned, local consumers will suffer from higher prices, creating pressures on cash-strapped governments to cushion the blow. So, while higher commodity prices have boosted some countries’ revenue, the downside in terms of political risk will be greater.

How are these developments likely to affect upcoming elections?

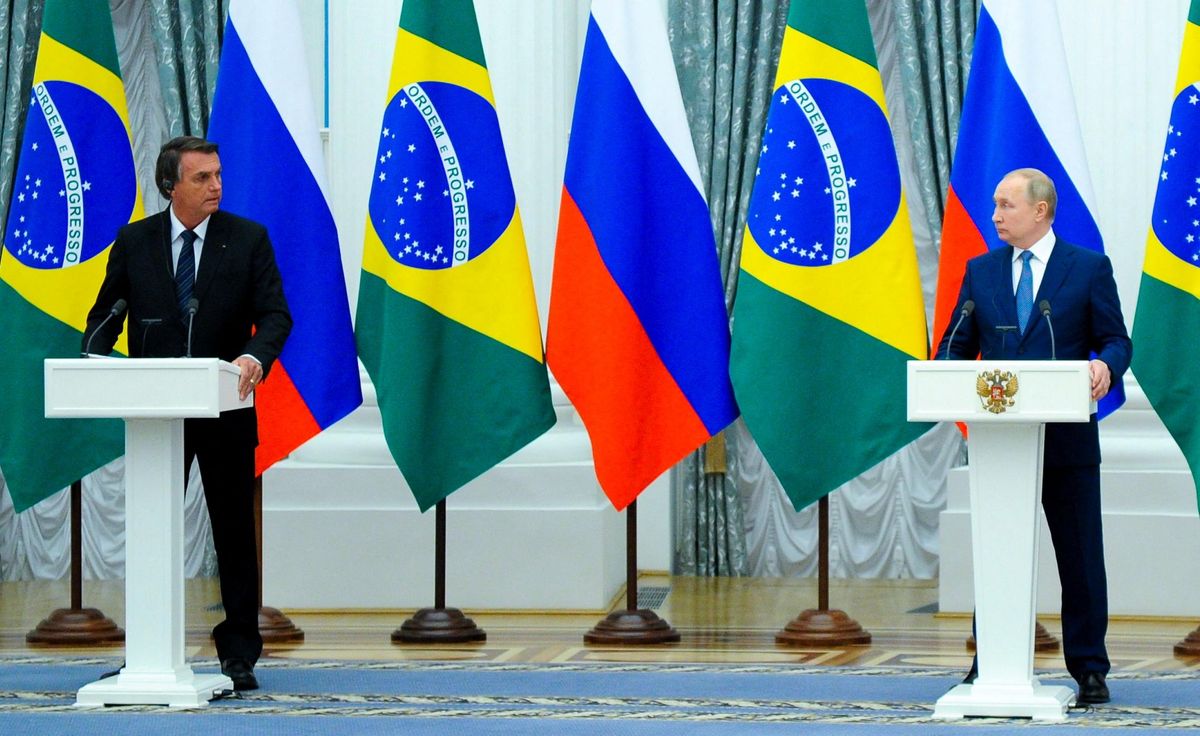

Like the pandemic, the effects of the Ukraine conflict and resulting inflation shock have exacerbated political headwinds for incumbents and added momentum to a leftward shift in the region’s politics. This means trouble for Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who faces an uphill battle for reelection in October against former leftwing president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and an added boost for Colombia’s Gustavo Petro ahead of May elections there. Polling suggests that Petro is on track to become Colombia’s first leftist president.

What are the geopolitical consequences in terms of relations with Russia, China, and the US?

Most countries in the region are aligning with the US, except for those that abstained from March’s UN resolution condemning Russia’s invasion. These included the leftist-run countries Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba, and Nicaragua in addition to an apparent outlier: the populist-run El Salvador. President Nayib Bukele now seems to be orienting himself towards Russia and has taken to social media to attack the US’s credibility on the crisis — potentially in a bid to bolster crypto as a financing prospect and adding to his already confrontational relationship with the Biden administration. Other countries that have maintained good relations with Russia in the past — including Brazil and Argentina — now face pressure to tread carefully if they want to avoid diplomatic and economic repercussions from the US and Europe. Additionally, if Western sanctions push Russia (even) closer to China, Beijing’s interest in solidifying economic ties to Latin America is likely to grow given China’s broad economic diplomacy efforts and attractive financing offers for many leftist leaders in the region.

- Moisés Naim: With inflation & low trust in democracy, Latin America faces perfect storm for nasty politics - GZERO Media ›

- Colombia's new president: Biden team aware the war on drugs has failed - GZERO Media ›

- Colombia's new president: Biden team aware the war on drugs has failed - GZERO Media ›

- Colombia's new president Gustavo Petro: Biden team aware the war on drugs has failed - GZERO Media ›