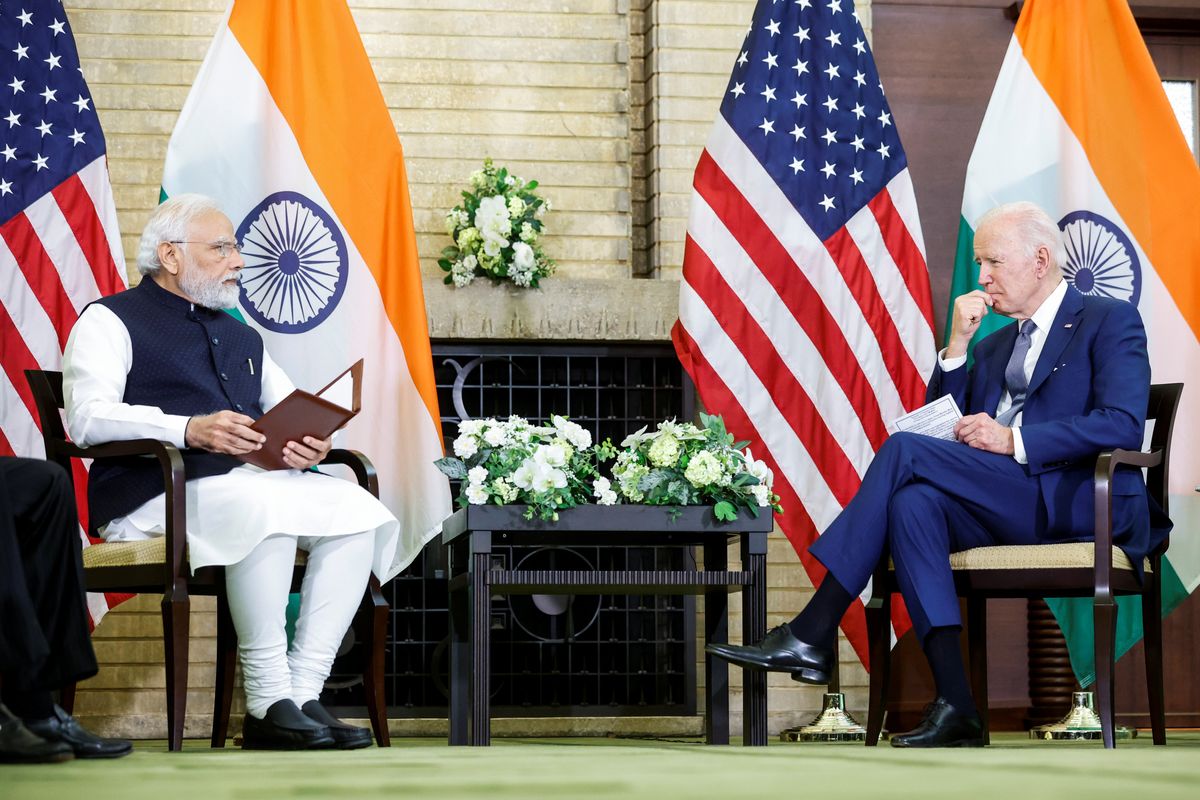

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be just the third world leader to receive state-level honors from US President Joe Biden when they meet in Washington, DC, on June 22. Modi and Biden want to send a strong signal to the rest of the world (especially China) about the strength of the bilateral relationship: The US is engaged in a struggle to push back against China’s expanding global influence, while India is locked in an intensifying economic and geopolitical rivalry with its neighbor that has prompted fatal border clashes.

We spoke with Eurasia Group’s US Director Clayton Allen and South Asia Practice Head Pramit Chaudhuri about what to expect from this week’s US-India summit.

What is on the agenda?

Allen: The US will offer major military tech and hardware transfers and is looking for India to approve plans for new semiconductor manufacturing to offer an alternative to Chinese-based supply chains. Beyond these concrete agreements, expect discussion, but perhaps not much in the way of tangible progress, on a host of trade and economic cooperation issues, such as possible Indian participation in the trade pillar of the US-backed Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.

Chaudhuri: The primary deliverable is expected to be an authorization for India to manufacture General Electric’s GE 414 jet engine. To enable the deal, the US has had to find a way to cut through a thicket of Cold War-era regulations restricting access to US defense technologies to countries that have signed a formal defense treaty with the US, which isn’t India’s case.

Why is the jet engine important for Modi? What else does he want from Biden?

Chaudhuri: India has embarked on a push to build its own military aircraft and wean itself off reliance on Russian-made equipment. It is finalizing the design of its Advance Medium Combat Aircraft and needs foreign technologies, especially for the engine, but insists on doing the manufacturing at home. The GE 414 is thus a major test of the strategic relationship as well as a precedent-setter for future defense technology transfers.

Modi will also be seeking greater alignment of the two countries’ industrial policies. India is one of the countries that has complained about the subsidies given to domestic manufacturers in the US’s CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. More broadly, the high-profile meeting offers the opportunity for favorable press coverage as Modi starts to prepare for 2024 elections and to garner praise for his green policies.

What does Biden want from Modi?

Allen: For Biden, the whole point of the visit is to draw New Delhi closer to Washington's views on tech, trade, and defense, all with an eye to competing with China and isolating Russia. Sealing a deal for India to domestically produce new US-deigned jet engines is a crucial part of this effort. For Washington, the deal is a foothold to become a core defense supplier to New Delhi. To this end, the US will also likely seek to advance the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology launched earlier this year to deepen the US-India cooperation on defense manufacturing.

An agreement to expand semiconductor chip production in India is another potential win for Washington. US plans to "de-risk" supply chains from China have run up against the reality that most suppliers are still heavily reliant on Chinese production. Beyond just producing new chips, the US and India are also expected to agree on technology sharing to boost long-term growth in the Indian tech sector, a key building block to standing up India as a direct competitor to China.

How would you assess the current state of US-India relations?

Allen: Steadily improving. The US sees India as a natural choice for a close partnership, given its rapidly growing economy and robust manufacturing sector. However, efforts at alignment will need to overcome long-standing US concerns over protectionist Indian trade policies that hinder US investment.

Chaudhuri: Modi has been irked at Washington's occasional comments on Indian human rights issues. Nonetheless, Biden and Modi have chosen to focus on what they can do together. The two now regularly meet at multilateral events, most recently at the G-7 and the Quad summit meetings in Japan. There are other signs of deepening ties. The US became India's largest trading partner last year and is set to issue one million travel visas to India this year.

Why do the US and India disagree on Russia-Ukraine but (mostly) agree on China?

Allen: In Washington's telling, its security versus economics. The US views India as reluctant to break away from its longtime defense supplier (Russia) but very willing to take any opportunity to bolster its position relative to its regional economic rival (China). In the long term, the US expects that India's economic interest in competing with China is the more powerful motivator, especially given Russia's pullback from defense partnerships owing to its focus on Ukraine.

Chaudhuri: India has been trying to maintain a neutral relationship with Russia as it goes head-to-head with China but is starting to see this strategy as unviable as Moscow becomes more subservient to Beijing. Its relationship with China, meanwhile, is in terminal decline amid the resumption of fatal clashes along the Himalayan border between the two countries. India has deployed a quarter-million troops to the region and has begun purging Chinese products and investment from critical infrastructure and the digital sector. Though previously wary of an alliance-like relationship with the US for fear of China’s reaction, Modi seems prepared to push the envelope on this.

Amid the huge demand to attend Modi’s events at the recent G-7 summit in Japan, Biden reportedly told Modi he should ask for his autograph. What does that say about their relationship?

Allen: It’s an interesting corollary to Biden's much-publicized "fist bump" with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Both Modi and MBS are leaders of key geopolitical players who appeared to have a strong personal rapport with Biden's predecessor, Donald Trump, and are both the focus of (varyingly successful) US efforts at influence projection. Yet Biden sees the personal relationship with MBS as more problematic than that with Modi.

Chaudhuri: My understanding is that Modi and Biden got along very well right from the start. The Biden administration sees Modi as the most enthusiastic supporter of the green transition among emerging economy leaders and wants to support him on this. Though it is true that Modi and Trump are both right-wing politicians, there is very little ideological connection between the right wing of the US and of India. Modi has passed legislation in favor of transgender rights, freer abortion, and expanded welfare. The US-India relationship is more about an alignment of interests than ideology.

Edited by Jonathan House, Senior Editor, Eurasia Group.