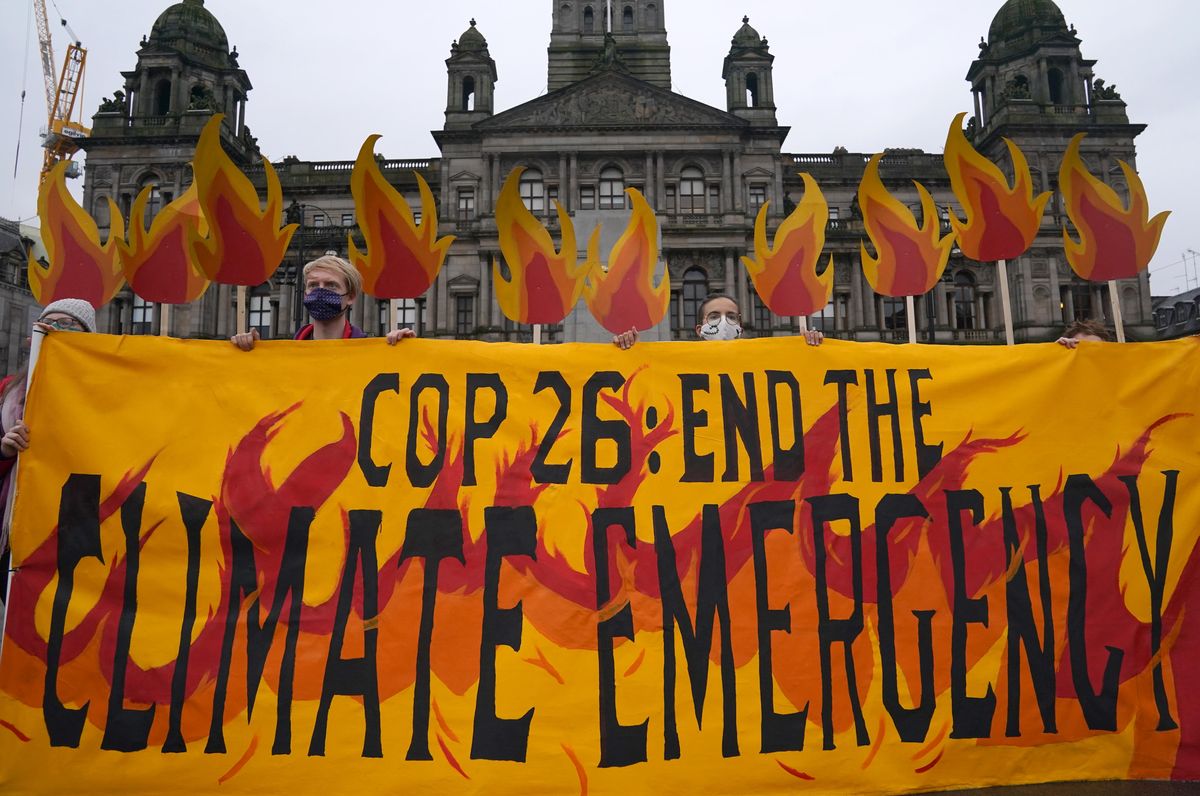

Over 100 world leaders are gathering in Glasgow, Scotland, for the UN's annual climate summit from 31 October-12 November. It is the 26th gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, a treaty signed in 1992 by about 150 countries to rein in the greenhouse gas emissions causing global warming. Amid mounting evidence of the risks posed by climate change, both advanced and developing countries will be under pressure to make more ambitious emissions-reductions pledges at the event known as COP26. We spoke with Shari Friedman, managing director for climate and sustainability at Eurasia Group, to get a better idea of what to expect.

Why is COP26 important?

While there is a COP meeting every year, this one is particularly important because it will revisit the commitments enshrined in the landmark Paris Agreement of 2015, which aims to limit global warming from preindustrial levels to "well below 2 degrees Celsius." Signatories were required to lay out their plans for meeting this goal in so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). But climate science has continued to evolve, and the consensus is now that temperature increases need to be limited to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius to avoid the worst and most irreversible effects of global warming. To meet that goal, scientists believe the world needs to halve its emissions by 2030 and reach "net zero" by 2050. Net zero refers to a situation in which greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere are offset by natural processes removing them. Consequently, the national delegations to COP26 will be under pressure to outline a clear and feasible trajectory for more ambitious emissions-reduction efforts.

Do you expect them to meet this challenge?

While there will be progress, contributions will likely not put global emissions on a path to meet net zero by 2050. It's true that there has been a flurry of activity in the run-up to COP26. Over 116 countries have already presented new NDCs. The EU for example, has submitted its Fit for 55 proposal, outlining a 55 percent reduction in emissions by 2030, and the US has presented a plan to limit emissions by 50-52 percent by 2030, though political obstacles have raised doubts about whether it can follow through. While other countries have increased credible near-term targets, many others have either not offered new measures in their NDCs or have made insufficient or long-term pledges without concrete near-term plans. Other top polluters such as China, Indonesia, Russia, and Saudi Arabia have made commitments to reach net zero later than 2050.

What other topics will be discussed?

Developing countries will be sure to demand industrialized countries cough up the $100 billion in annual funding they promised in 2009 (but never fully delivered) to help implement costly projects to move away from polluting forms of producing energy. The delay has added to developing country discontent about being asked to reduce their emissions to solve a problem that was largely created a long time ago by now-rich countries when they were industrializing. Another important topic is creating a rulebook that enables emissions trading among countries on a project level.

Will anything be achieved beyond the formal negotiations?

Yes, outside of the country negotiations, we are seeing sector initiatives. These include the Global Methane Pledge, a US-EU plan to reduce emissions of methane (a potent greenhouse gas) by at least 30 percent from 2020 levels; the Powering Past Coal Alliance of national and sub-national governments aiming to phase out coal-fired power stations; the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, which is seeking to protect 30 percent of the world's lands, freshwater, and oceans by 2030; and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, a grouping of financial institutions with assets of more than $100 trillion aiming to align emissions from their portfolios with net zero pathways by 2050.

How will soaring energy prices affect the talks?

This development will enable a dual political narrative. Climate advocates will say it shows the need for an accelerated energy transition and a quicker build-out of renewable capacity to ease supply constraints. At the same time, fossil fuel proponents will call for less stringent regulations and more clear investment signals to develop the fuels they say are more reliable and affordable. That the EU, a global leader in climate policies, is now struggling with soaring energy prices will cause some to doubt whether transformational change is possible.

What do you expect post-COP?

International negotiations, while important and a significant opportunity to act collectively on a global scale, are not the only way forward. In the past few years, the private sector has made significant progress, and we expect to see continued pressure from investors for companies to mitigate climate risks. Meanwhile, proliferating corporate net zero commitments will have knock-on effects across supply chains, and the increasingly evident impact of climate change will shift voters and consumers to become more sensitive to the issue. Regardless of the outcome in Glasgow, COP's overall objective is shifting in an important way: With the science increasingly clear and less subject to interpretation (we know what needs to happen and by when), the conversation around climate change is shifting to one that is less about negotiation and more about transparency, acceleration, and accountability.

Shari Friedman is managing director of the climate and sustainability desk at Eurasia Group.