Over the last 60 years or so, the United States and Canada have admitted tens of millions of immigrants. In 1960, fewer than 10 million people in the US were foreign-born – a mere 5% of the population. Today, there are over 46 million immigrants in the country, comprising roughly 14% of the population.

By contrast, in 1961, Canada was home to 2.8 million immigrants, or 15.6% of the country – considerably more than the US per capita. In 2022, Canada welcomed a record number of people with over 430,000 arriving, and the latest census in 2021 found over 8.3 million – or nearly 1-in-4 people – are immigrants or permanent residents.

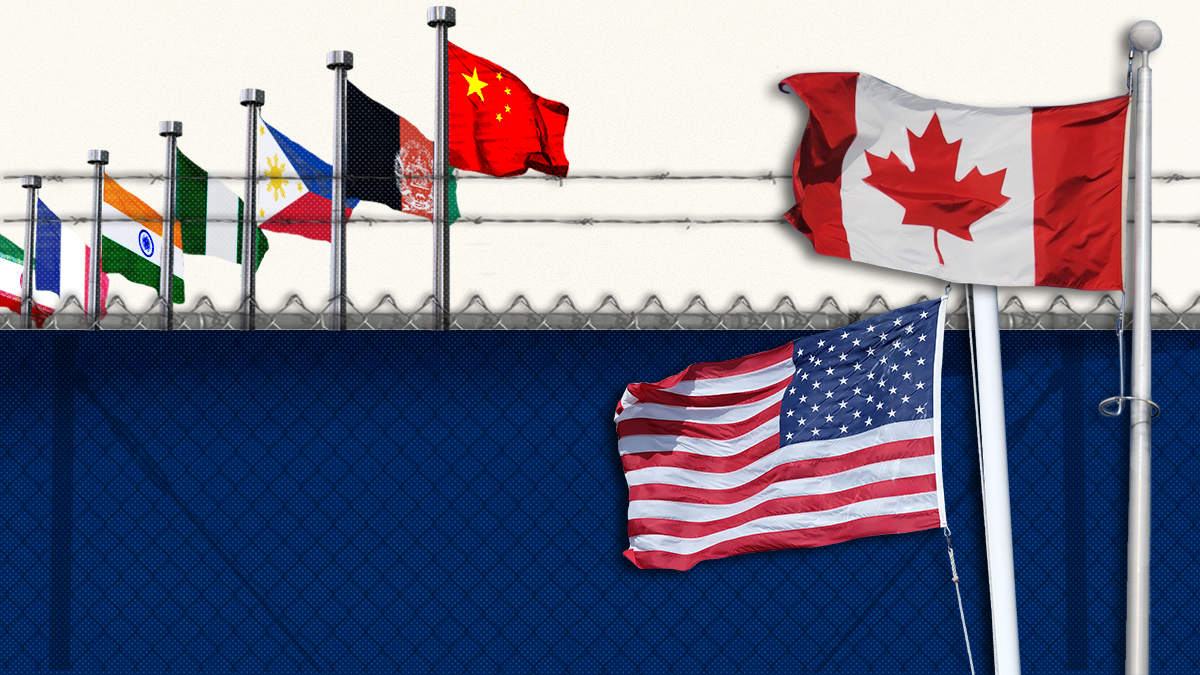

The popular imagination in Canada might assume the country is more welcoming, evolved, and progressive on immigration than the US, but the two countries have more in common on this issue than you might expect.

As crises in housing, education, healthcare, and affordability in general persist – and worsen – Canadians and their leaders are increasingly likely to consider immigration a source of tension.

Liberal immigration woes

In 2022, Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government announced new, higher, immigration targets that included a plan to incrementally increase the number of permanent residents Canada accepts from 405,000 in 2021 to 500,00 in 2025. At the same time, the number of temporary residents was rising. There were roughly 2.2 million non-permanent residents – including upward of 900,000 international students – in Canada in 2023. That’s nearly 50% more non-permanent residents than in 2022.

But now, amid a housing shortage, Canada’s Immigration Minister Marc Miller is considering ideas to ‘rein in’ the number of temporary residents in the country, including a potential cap on how many are admitted. Miller is taking particular aim at foreign students – who are critical to university funding in the country – saying the system is “out of control.” Housing Minister Sean Fraser is even open to the idea of basing immigration numbers on the housing supply – an idea supported by Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre.

Earlier this week, news broke that the federal government is considering restricting the number of international students in certain provinces that are facing acute housing shortages. A source cited Ontario, British Columbia, and Nova Scotia as potential targets. The minister’s office has not confirmed that such a plan exists.

A recent poll by Leger, in November 2023, found that about 75% of respondents say an increase in immigration is exacerbating the housing crisis in Canada. Roughly the same number say it’s putting pressure on the healthcare system, while two-thirds say it’s affecting the education system.

The poll also found softening support for welcoming newcomers, including nearly 48% who believe Canada should lower its immigration rate. That number includes 64% of Conservatives who wish to see fewer newcomers compared to 29% of Liberals, indicating a partisan divide.

The cross-partisan battle for newcomers

For decades, immigration in Canada has enjoyed a popular, cross-party consensus in support of newcomers that included broadly positive discourse around the issue, though typically that support has been tied to immigrants as a labor source and newcomers as economic drivers. In the United States, the public and politicians share the same view, with immigrants cast as economy builders, but the issue has been heavily politicized along partisan lines while irregular migration has shaped attitudes and increased anti-immigration sentiment.

Graeme Thompson, a senior analyst with Eurasia Group's global macro-geopolitics practice, says that in Canada both the Liberals and Conservatives want to win the support of diaspora communities and newcomers, which has affected the politics of immigration in the country.

“Both parties want to win votes in suburban Vancouver and Toronto. They’re fishing in the same pond when it comes to pursuing the votes of new Canadians,” he says. Consequently, neither party wants to alienate immigrants with an anti-immigration posture.

American attitudes similar to Canadian

In the US, however, not only has the partisan politicization of immigration across party lines led to greater controversy, says Thompson, but irregular migration along the southern border has also shaped opinions about immigration and produced toxic discourse and politics.

Despite the sharp partisan divide, Americans nonetheless support immigration and US numbers aren’t so different from Canadian numbers. In July 2023, Gallup found that 68% of the country believed immigration was a good thing, and a majority wanted to see the same number or more immigrants. Similar to Canadian numbers, 41% of people wanted to see fewer immigrants, up from an all-time low of 28% in 2020. That 41% is conditioned by partisan affiliation, with 73% of Republicans wanting to see the number of immigrants decline compared to 18% of Democrats – a more pronounced partisan split than in Canada.

A hot-button election issue?

With the US presidential election coming in November, a Canadian election due by October 2025, and persistent affordability and social service issues, immigration is set to become a critical issue on both sides of the border.

In the US, Thompson expects immigration to play out as it typically does, including a Republican focus on irregular migrants and strengthening the border.

“In a really powerful sense, as a hot-button issue, immigration is going to be front of mind for American voters,” he says. That’s especially true as irregular crossings are up along the Mexican border and governors are sending migrants to northern cities, including New York, where Mayor Eric Adams says the city can’t handle the numbers.

In Canada, Thompson says, the immigration framing will be more a derivative of “bread and butter issues.”

“I don’t think Canadians will turn anti-immigrant. But I think they will become more skeptical in the context of housing shortages, affordability issues, and strains on the healthcare and education systems.”

Immigration is set to be a central issue in both Canada and the US in the coming months and years and will shape political fortunes as we approach two big elections. And while both countries are receptive to immigrants, there’s a risk that pro-immigration attitudes in the US decline.

There’s also a risk that Canada’s longstanding, cross-partisan consensus on welcoming newcomers fractures as crises in housing, education, healthcare, and affordability persist. The need to find policy solutions that respond to pressures without scapegoating newcomers is important and will test the current crop of leadership, threatening political incumbents – and immigrants, too.