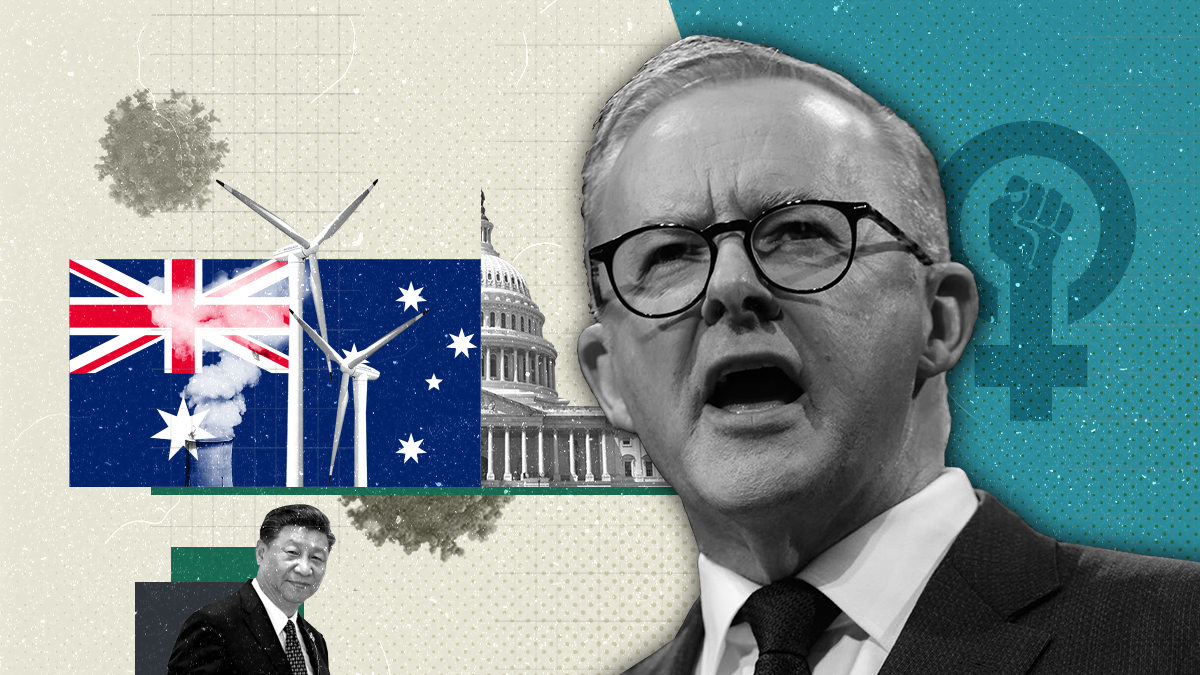

Anthony Albanese, Australia’s newly elected prime minister, hasn’t wasted any time since being sworn in on Monday. After taking the oath of office, he immediately boarded a flight to Tokyo to meet with Australia’s Quad partners – India, Japan and the US – to talk China.

Indeed, the unusually hasty political transition was not lost on President Joe Biden, who quipped that “if you fall asleep that's okay” – a nod to Albanese’s campaign trail hangover and/or jet lag. But Albanese fought the urge to nap because he has a jam-packed agenda, which includes bilateral meetings with Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Fumio Kishida as well as Biden.

Albanese, the son of a single mum who grew up in public housing in Sydney, takes the reins as the country’s economy is still reeling from the enduring pandemic. What does the election of his center-left Labor Party mean at home and abroad?

The view from home: A massive shakeup

Albo didn’t win; ScoMo lost: The 2022 federal election will go down in history as a watershed. The Labor Party’s victory ended a decade of conservative rule under the Liberal-National coalition headed by Scott Morrison. It’s only the fourth time since World War II that Labor has won an election while serving in opposition.

Still, the results were hardly a ringing endorsement of Albanese’s blah vibe and light-on-detail policy agenda: just one-third of the Australian electorate cast a ballot for the Labor Party, less than it scored in 2019 and a record low for an incoming government.

The teal wave. To be sure, Labor picked up seats and managed to make gains in some traditionally safe Liberal electorates. But the biggest political shift is reflected in the rejection of the dominant mainstream political parties in favor of half a dozen independent candidates – mostly professional women backed by a pro-climate group – in urban areas where the Liberal Party hemorrhaged support.

This phenomenon – dubbed the teal wave because they appeal to fiscal conservatives (blue) who care about climate change (green) – saw moderate women, some of whom have traditionally been aligned with the Liberals, campaign on a more ambitious climate agenda. They also criticized the incumbent party’s macho-brand of politics, whereby it has long failed to nominate women to safe seats or implement gender quotas.

This was a broad rebuke of the Australian political system. For years, both major parties had been accused of sexism and belittling women within their ranks, but the issue was certainly worse within the Liberal Party, a boy’s club that failed to elevate female leaders. A slew of terribly managed sexual assault allegations also contributed to perceptions that the government was woefully out of step with evolving societal expectations about promoting gender equality.

What’s more, the Senate will now be 57% female, while 37% of the House of Representatives will be represented by women, up from 48% and 29% respectively.

Climate. The number one issue for Aussie voters in this election was climate change (30%), followed by the cost-of-living crisis (13%), and the state of the economy (13%). Morrison, who made only tepid commitments to reduce carbon emissions despite the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change calling out Canberra for its “lack of consistent policy direction” on the issue, didn’t heed warnings that Aussies wanted him to show greater commitment to the climate and less love for coal.

While Labor’s vague climate agenda is only slightly more ambitious – they aim to mitigate carbon emissions by 43% by the end of the decade compared to the Liberals’ pledge of 26%, while also refusing to ditch coal exports – the party hasn’t adopted the Liberal Party’s notoriously combative stance to the climate conscious community.

“Australian men and women have sent a very clear message to our parliament that we are absolutely committed to addressing the perilous state of climate change,” says Carol Schwartz, founding chair of the Women’s Leadership Institute of Australia.

“We have also sent a clear message that we demand that women’s voices be heard alongside those of men and that we share power, decision-making, and leadership equally,” she says.

The view from abroad: (Mostly) the same.

Australian politics are mostly immune from the sort of globalist v. isolationist tug-of-war seen in the US and Europe. As such, we’re unlikely to see much daylight between Albanese and his predecessor on major foreign policies. For instance, Australia signed on this week to the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, a new push by the Biden administration to expand the US’ economic clout in the region.

Despite recent warnings from Chinese state media that he better play nice, Albanese has made clear that he will continue his predecessor’s tough-on-China stance, and work with Washington and other allies to counter Beijing’s bellicose activities in the region. Still, he has shown a willingness to chat with his Chinese counterpart in hopes of improving the relationship in exchange for Beijing ditching trade bans on Aussie goods. (Xi Jinping, however, doesn’t take kindly to ultimatums.)

The ongoing row with China is certainly top of the agenda at the Quad summit, particularly as China’s foreign minister also plans this week to visit the Solomon Islands. This comes just a month after Beijing signed a security pact with the Pacific state, which raised fears that China could be seeking to build a military base on Australia’s doorstep.

Indeed, Canberra and Washington are extremely concerned about China’s ongoing courting of other Pacific islands, like Kiribati. Though it has a meager population of just 120,000 – and a name few people have ever heard of – Kiribati’s strategic positioning midway between the Americas and Asia (and vast fishing resources) make it fertile ground for a great power showdown.

Jump! High high? Whatever the Biden administration wants from Australia – which has long followed Uncle Sam into battles far and wide – you can be sure that PM Albanese will acquiesce.