Last Thursday, after Joe Biden promised during his State of the Union to build a pier to deliver aid to Gaza, Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet shook the president’s hand, congratulated him on the speech, and urged him to push Israel to do more on “humanitarian stuff.”

Biden, caught on a hot mic, nodded in agreement and said he was pressing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. “I told him, Bibi, don’t repeat this, but we are going to have a come-to-Jesus meeting.”

The next day, in the multicultural Toronto suburb of Mississauga, Justin Trudeau's International Development Minister Ahmed Hussenannounced that Canada would resume funding the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees. Israel has alleged that 12 employees were involved in the Oct. 7 attack on Israel, leading most Western countries to withdraw aid.

Unhappy progressives

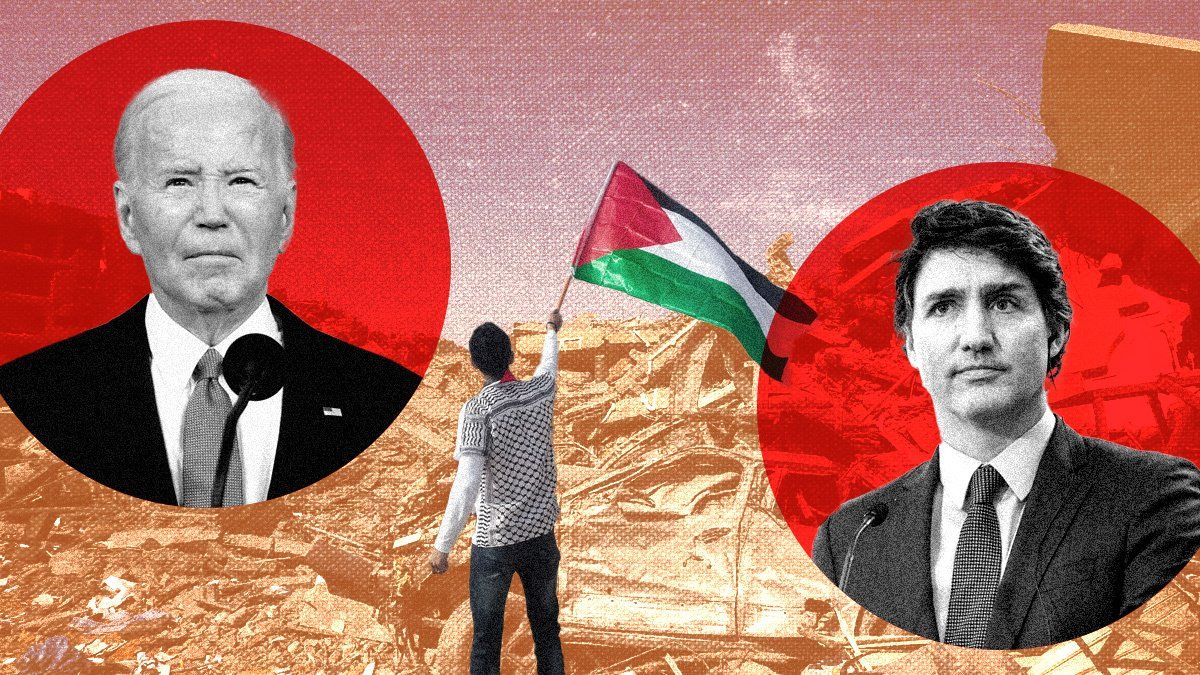

Both Biden and Trudeau are responding to pressure to shift their positions on the war in Gaza, which has rattled their electoral coalitions, posing serious challenges for them as they head toward elections in November in the United States and 2025 in Canada.

The White House is aware of the problem. Biden’s aides have had to take steps to avoid pro-Palestinian protests, booking him into smaller venues and holding back event details until the last minute to keep protesters from being able to disrupt him. That is making it hard for him to get his message about student loan relief out on university campuses.

The horrible death toll in Gaza, where thousands of civilians have been killed since October, has led to despair and anger among progressives, not just among people with roots in the Middle East, but among young people and people of color.

There has been a significant generational shift in public opinion. A December New York Times poll found 46% of 18-to-19-year-olds are more sympathetic to Palestinians, compared to 27% who are sympathetic to Israel.

“I tell people all the time, 50 years ago when we had a demonstration from the White House it would be 50 people, all of whom had an Arabic accent, and today it’s tens of thousands of people, and it's a group as diverse as America that's showing up,” says James J. Zogby, founder of the Arab American Institute.

Michigan in the balance

In February’s Democratic presidential primary in Michigan, 13% of voters chose “uncommitted,” sparking similar protest movements in other states, a way for progressives to signal their unhappiness with Biden’s support for Israel in the Gaza war. But unlike the other states, Michigan, home to about 500,000 Arab Americans, is vital if Biden hopes to stay in the White House.

“Michigan had a huge impact because it is difficult to come up with a map where Democrats win the White House without Michigan in the mix, and the percentage of Arab voters in Michigan is high enough to make the difference,” says Zogby.

While the fear isn’t that these voters would flip sides for Donald Trump, the threat is real, says Clayton Allen, US director for the Eurasia Group. “Michigan is a great example where if you see the decline in Arab-American support hold through the election, that would be enough votes — if they would not show up to vote … — that would be enough to erase what had been his margin of victory in 2020.”

Nobody on Trudeau’s side

The situation in Canada is similar. Progressives are so frustrated with the Trudeau government’s position on the war that urban areas once considered safe for the Liberals may now be out of reach for the party.

Trudeau’s fence-sitting on the Gaza war has not endeared him to pro-Israel voters either.

“The Liberal Party has lost, largely, both communities, because they’ve tried to have it both ways,” says pollster Quito Maggi, of Mainstreet Research.

“For electoral purposes, it’s not really great to have nobody on your side,” says one Liberal organizer.

The Liberals have been behind in the polls for so long that some would like to replace Trudeau before the election, but a leadership race while the war continues could be dominated by arguments over Gaza, potentially damaging the party.

The war is not causing similar problems for conservatives in either country, because their coalitions don’t include progressives who are angered by the bombing. They can sit back and watch as their progressive opponents struggle to keep their coalitions together.

Both Biden and Trudeau appear to be in no-win positions. They are angering their progressive bases but would anger other constituencies if they move too far the other way.

“Outside of that young progressive block, most US voters, in total, support US military backing of Israel,” says Allen. “So Biden does bear a risk if he skews too hard to the left. Everyone else can attack him for abandoning Israel. I think that's been one of the limiting factors. It's why we see Biden try to walk this tightrope.”

Both leaders would benefit from bringing the temperature down, which will only happen after the bombs stop falling on Gaza. Few outside Canada have much reason to be greatly concerned about Trudeau’s position, but the United States provides $3.8 billion in military aid to Israel every year, which gives Biden leverage over Netanyahu.

He may need to use it soon to give himself time to win back the progressives whose votes he needs to keep Trump out of the White House.