Since the end of the Cold War, every US president has tried to boost relations with India. After all, closer defense ties with the world’s largest democracy would advance US interests in Asia, and an opening of economic ties with the world’s most populous country would create enormous opportunities for US companies and consumers.

Bill Clinton’s bid to boost ties with Delhi all but ended when India tested a nuclear weapon in 1998, but George W. Bush dropped the resulting sanctions on Delhi, recognized India as a nuclear power, and signed a landmark civilian nuclear deal with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

Barack Obama lifted a US travel ban on Prime Minister Narendra Modi, imposed in response to a 2002 massacre of Muslims in the state where Modi then served as chief minister, and welcomed him to the White House in 2014. Obama later recognized India as a “major defense partner.”

Donald Trump imposed tariffs that hit India’s economy, but he also revived the so-called Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with India, Japan, and Australia in response to a more assertive China.

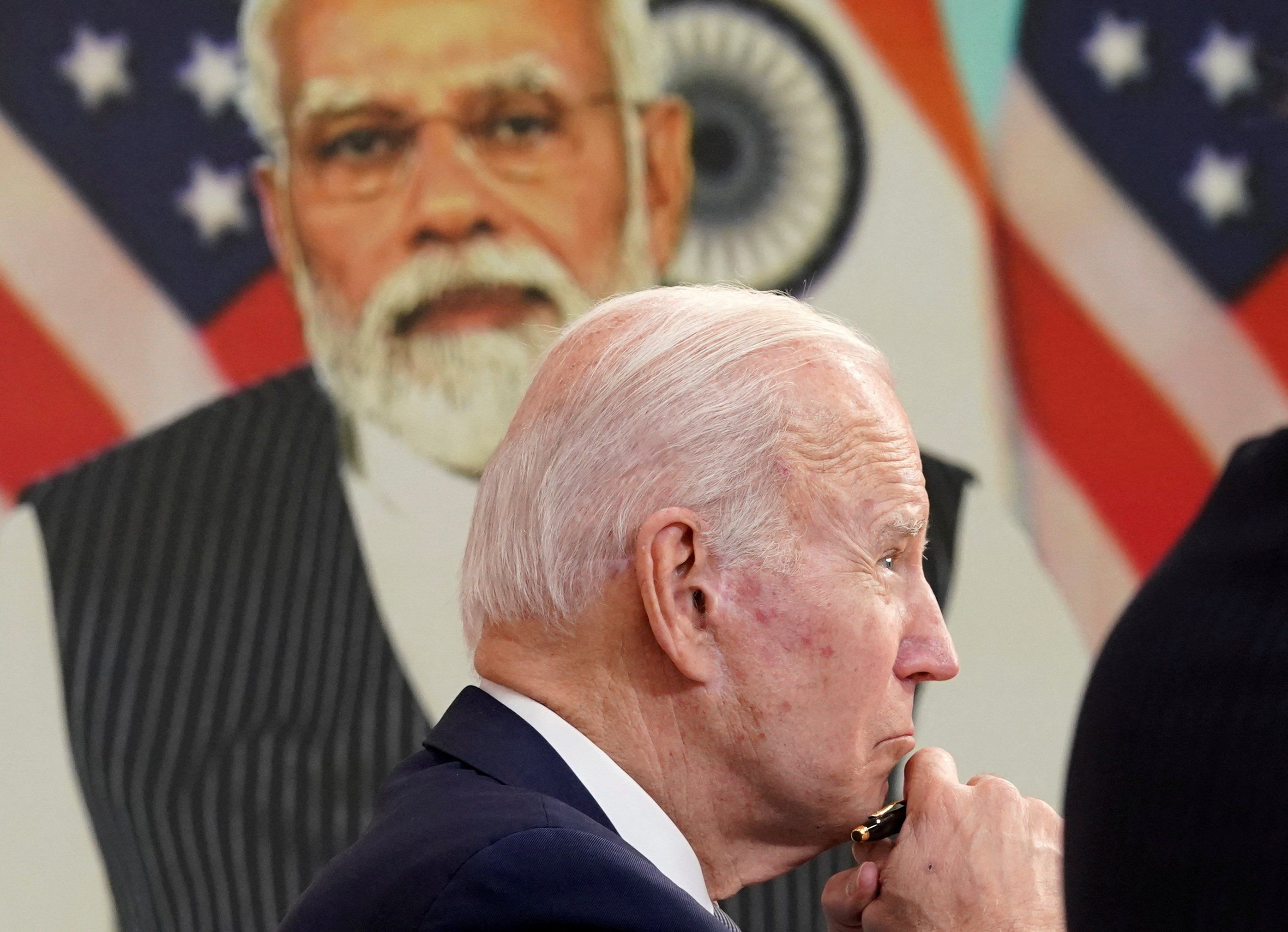

Next Thursday, President Joe Biden will take his shot at deepening ties with India, as Prime Minister Modi arrives at the White House for a much-anticipated state visit, his first since meeting Obama nine years ago.

The backdrop for their conversations will include all the things that might bring the US and India closer together and the issues that have long limited how much they can accomplish. Shared anxiety over a more assertive China and the opportunity for India, the world’s largest arms buyer, to purchase powerful weapons and technologies the US typically reserves for its treaty allies will give them plenty to talk about. The US, already India’s top trade partner and largest direct investor, is happy to replace Russia as India’s lead arms dealer.

Biden and Modi are also expected to discuss the so-called “initiative on critical and emerging technology,” which creates US-India projects to develop defense-related advanced technology centered on semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing. This is the area where Biden and Modi are most likely to make news.

But, while Biden and Modi will acknowledge their shared security and economic interests, Modi continues the Indian tradition of presenting himself as a voice for the developing world. In that role, differences over who will bear the heaviest burdens in the fight against climate change loom large.

That’s why Biden is expected to offer substantial US investment next week in projects designed to boost development in countries of the “Global South,” targeted with guidance from Modi.

If Biden and Modi discuss human rights – the treatment of India’s Muslim minority by members of Modi’s Hindu nationalist government and party, in particular – it’s likely to be within limits agreed in advance by the US and Indian officials who prepped the visit.

More broadly, while Americans have long wanted a more productive partnership, Indian leaders, Modi in particular, value their country’s independence of action.

In short, next week’s visit will offer big opportunities for both Biden and Modi. But US and Indian leaders have been here before, and the US-Indian relationship has remained a work in progress for decades.