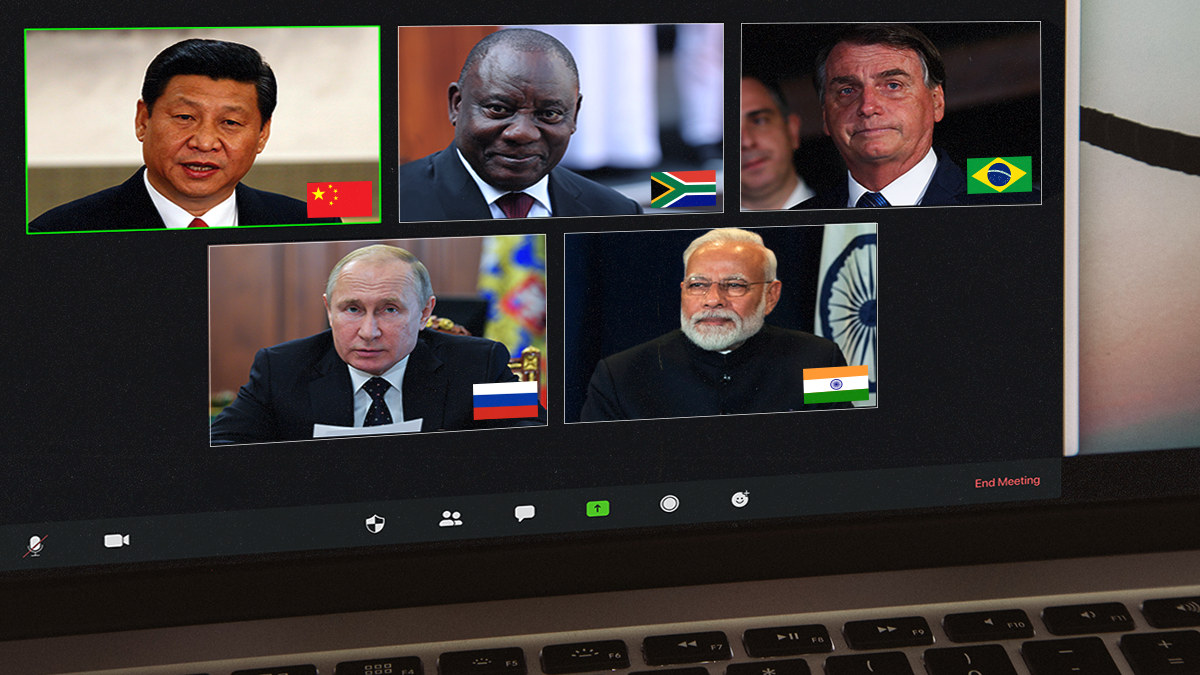

Before the heads of the world's most "advanced" economies meet this weekend in Germany for the annual G7 summit, the leaders of the top five "emerging" ones — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, aka BRICS — are holding their own (virtual) summit in Beijing on Thursday.

BRICS became a thing 21 years ago, when a Goldman Sachs economist coined the term — initially with a small "s" — to predict the emerging market economies that would lead global growth in the future (this came true for China, not so much for the rest). Now they’ve established a formal presence, set up their own development bank, and claim to represent the entire Global South.

Still, the group’s meetings rarely get much buzz. But this year is different. Why?

For one thing, it's the first time Vladimir Putin will attend a major multilateral get-together since Russia invaded Ukraine. Although the Russian president has met and talked on the phone with mostly non-Western leaders — and a few European ones — the optics of him being on the BRICS call with heavyweights like China’s Xi Jinping or India’s Narendra Modi are a big win for Putin. It’s also the latest sign that his standing in the Global South is not as diminished as the US and its allies hoped.

What's more, it might help Putin get back into the groove of attending such international events if he finally accepts Indonesia's still-open invitation to go to the G20 summit in Bali later this year.

It’s also an opportunity for major non-aligned powers to discuss new ways to trade with Russia while avoiding Western sanctions. For instance, the Kremlin wants BRICS countries to settle transactions in a basket of the groups’s currencies instead of the US dollar, and set up joint oil and natural gas refineries.

Interestingly, the BRICS countries all buy more stuff from Russia than they do business with each other. China and India are swooping up boatloads of Russian oil and gas at a steep discount, while Brazil is hungry for Russian fertilizer. South Africa, for its part, is less economically dependent on Moscow, yet eager to import more Russian commodities to bring down sky-high food and fuel prices.

Still, BRICS members don't see eye-to-eye on many things, which is hardly a surprise given the vast differences between them. China, by far the biggest economic power, sees itself as the leader of the group. That's never been accepted by India, which has a major beef with China over a disputed Himalayan border — arguably the biggest roadblock to wider BRICS cooperation.

Indeed, India is the odd man out. The Indians are both in BRICS and the Quad, a US-led security dialogue that Beijing views as Asia’s answer to NATO against China, and US President Joe Biden's Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, a loosely defined trade initiative that's also designed to counter growing Chinese influence in the region.

Modi wants to have it both ways: keep India neutral on Ukraine because it needs Russia's oil, and at the same time stay in US-led alliances to keep BRICS buddy China at arm's length.

Meanwhile, BRICS is (sort of) expanding. Argentina was recently invited to join its development bank as a first step toward full membership. Other potential candidates include Egypt, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, and Thailand — all of which took part in the BRICS foreign ministers’ video chat last month.

It’s unclear, though, what being part of the club would actually entail for new members other than gaining access to the pool of BRICS credit and getting an RSVP for the annual summit.

So, could BRICS become an alternative to Western-led fora like the G7 or the G20? Perhaps, says Akhil Ramesh, a fellow at the Honolulu-based Pacific Forum.

"It's a question of geopolitics, how world events play out, but they're certainly working toward that," he explains. “What they're trying to do is make it less of a unilateral world."

BRICS countries, Ramesh says, have taken note of what the West has done to Russia. China could be next if Xi makes a move on Taiwan, and both India and South Africa were sanctioned in the past over Delhi's nuclear program and apartheid. The stronger and bigger the group becomes, the better protected its current and future members will be against similar punishments to come.

“All of them know the impact of sanctions,” he adds. "So they want something that is more, I guess, in their mind, fair."