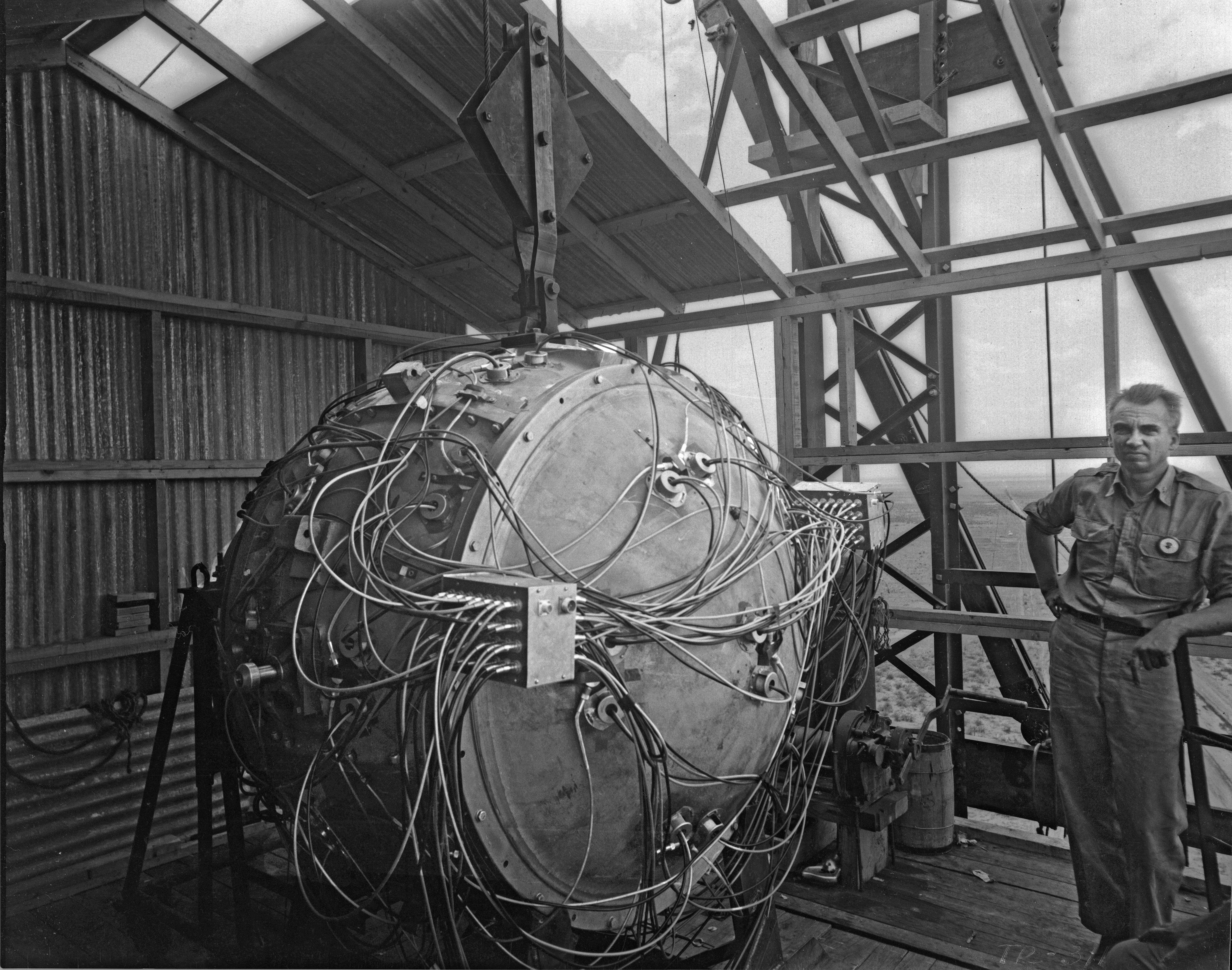

“Tickling the dragon’s tail.” That’s how the small group of physicists working at Los Alamos in the 1940s under the watch of Robert Oppenheimer described the dangerous job of assembling a nuclear core for the first atomic bomb. One wrong move and a chain nuclear reaction — the dragon — could have wiped them all out.

Even though the Manhattan Project was America’s most sensitive and secretive task — and the focus of the new Christopher Nolan film that opens tomorrow — Canada and the UK also contributed to the work. And at the very heart of it was a Jewish Canadian scientist named Louis Slotin, who emerged as the bomb assembler-in-chief. He worked with the radioactive material to build the core of the bomb — literally tickling the dragon by hand — a skill that led to his fame, but also to his gruesome, slow death by radiation poisoning in 1946.

Slotin was one of about 35 Canadian scientists working at Los Alamos. But Canada’s most crucial contribution — outside the academic work done in places like the famed Montreal Lab – was likely the Eldorado Mine on Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories, which supplied uranium to the bomb project. Canada’s uranium was hauled down from the north and refined in a lovely little Lake Ontario town between Ottawa and Toronto called Port Hope, before being shipped to Los Alamos to be used in Fat Man and Little Boy, the bombs that were eventually dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The US-Canada link was so strong that by 1944 the first nuclear reactor outside of the United States was built in Canada in a place called Chalk River, not far from Ottawa — which leads to another fascinating thread … In 1952, there was a nuclear meltdown at the Chalk River plant, and a 28-year-old American naval officer with expertise in nuclear power named Jimmy Carter — yes, the man who would go on to become the 39th US president — rushed in and prevented the accident from becoming catastrophic.

Still, as the new film “Oppenheimer” examines, developing the bomb remains a moral morass, one which Oppenheimer and Slotin openly struggled with. Were they, as Oppenheimer later claimed to have said, the destroyers of worlds, or did they save lives? That moral debate continues.

As nuclear fears reemerge with the war in Ukraine and the NATO alliance is reanimated in its purpose, it’s worth examining again how the world should handle its nuclear capabilities. While Oppenheimer’s later life was subsumed by political suspicion that he was a Communist (there is no evidence he gave the Russians any secrets), Slotin never lived to see that. In 1946, while working at Los Alamos, he was tickling the dragon’s tail by hand when there was an accident, and he was fatally irradiated. He cooked from the inside and slowly, painfully, melted down. His life is a stark reminder that the nuclear dragon is still very much alive, and as we covered recently on our GZERO World PBS program when Ian Bremmer interviewed the International Atomic Energy Agency chief Rafael Grossi, the dragon remains very, very difficult to tame.