As the global vaccination race heats up, the most populous country in the world is trying to do three very hard things at once.

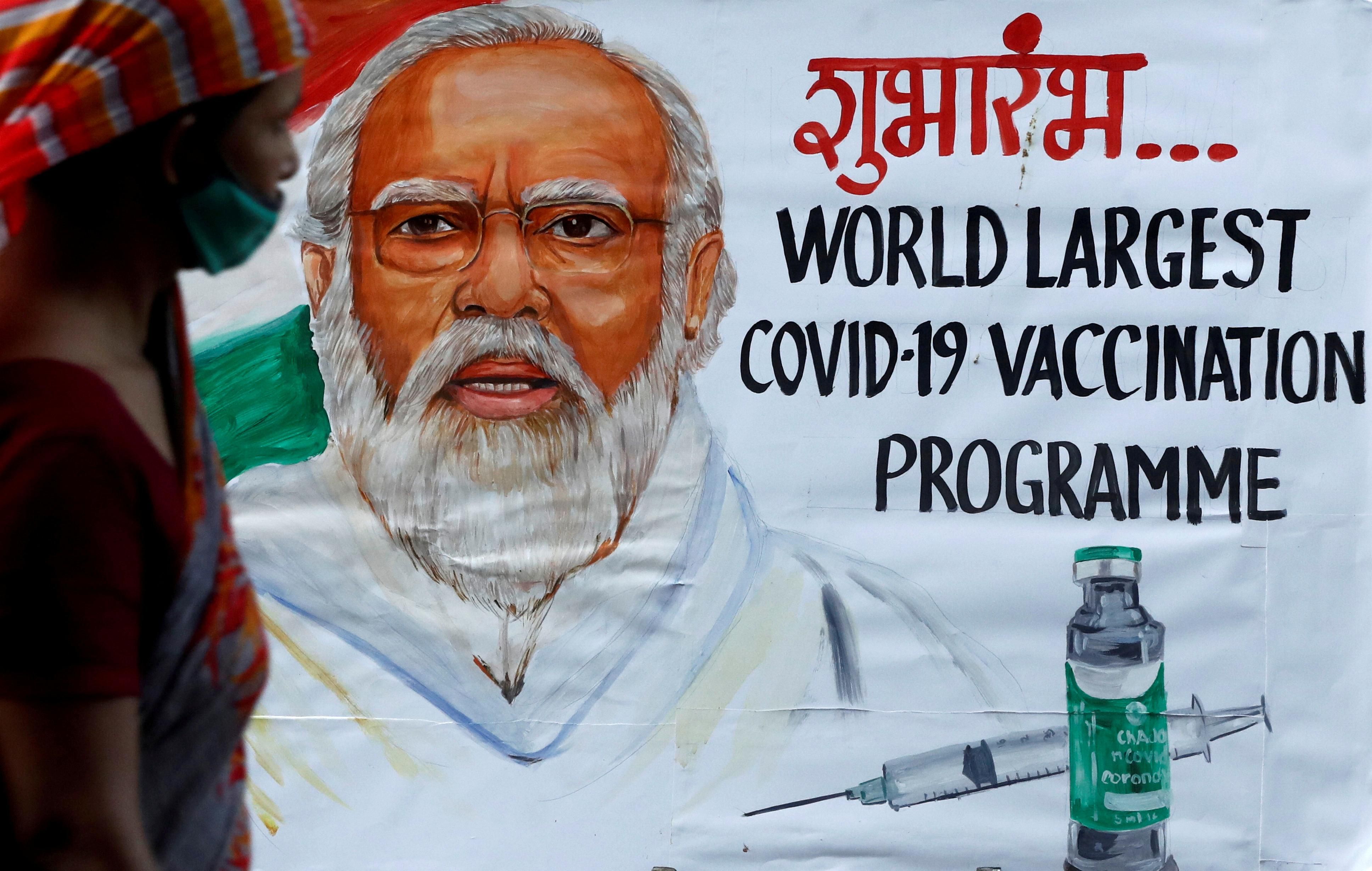

India, grappling with the second highest confirmed COVID caseload in the world, recently embarked on what it called "the world's largest" coronavirus vaccination campaign, seeking to inoculate a sizable swath of its 1.4 billion people.

That alone would be a herculean challenge, but India is also making hundreds of millions of jabs as part of the global COVAX initiative to inoculate low-income countries. And as if those two things weren't enough, Delhi also wants to win hearts and minds by doling out millions more shots directly to other countries in its neighborhood.

How will India pull off such a gargantuan task? It's still early days, but tough tradeoffs are already emerging fast.

Domestic mistrust. When India launched its COVID vaccination campaign in January, many were hopeful. The country had both the capacity to mass-produce (India makes about 60 percent of all vaccines globally) and the logistical infrastructure already in place to inoculate hundreds of millions of children against measles or tuberculosis annually.

But six weeks in, barely 1 percent of Indians have gotten their shots. Technical glitches are one reason. But another issue is widespread skepticism. Only 40 percent of Indians say they want to be vaccinated, according to the pollster Local Circles. A fishy approvals process for India's own locally-developed vaccine contributed to that. Earlier this week Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself took the jab in a photo-op bid to boost public confidence.

There's also a basic supply constraint which is forcing India's government to balance competing priorities.

Made in India vs India First. Global prospects for ending the pandemic depend heavily on India, which has committed to producing hundreds of millions of vaccines for Oxford/AstraZeneca, under the local name Covishield. But balancing that global demand against Indians' needs is proving tough.

Delhi has already warned once that it would delay COVAX commitments until it had inoculated a critical mass of its own population. And although it walked that back a bit, two weeks ago the Serum Institute of India — the main COVAX supplier — hinted it was under pressure to prioritize India's "huge needs."

One of those needs is vaccine "friendship." Prime Minister Modi calls his strategy "Vaccine Maitri," a Sanskrit word with Buddhist overtones that means friendship, goodwill, or kindness. Modi wants the world to see India as a benevolent power, using its vaccine manufacturing capacity to help countries in need.

Indeed, Delhi is set to ship shots to several nations in South Asia and beyond, often for free. But Delhi's largesse has a geopolitical coloring too: India is sending jabs to Bangladesh, for example, as part of a strategy to mend ties with Dhaka after the fallout of India's controversial 2019 citizenship laws, which stoked tensions with the majority-Muslim country. Meanwhile, unsurprisingly, no Indian-made jabs are headed for the 200 million people of long-time adversary Pakistan.

China is part of the story too. India's main rival for Asian supremacy is waging its own complicated campaign of vaccine diplomacy, sending millions of vaccines to countries across the developing world. Delhi wants to counter that, but is focusing closer to home: India is supplying millions of doses of Covishield to neighboring Nepal, where China's growing influence has been eroding India's sway in recent years, and to Sri Lanka, which is increasingly in play in the Asian rivalry between Beijing and Delhi.

Bottom line: India has chosen to do three very difficult and somewhat conflicting things. Succeeding at any one of them alone would be an impressive step in the longer fight to end the pandemic. But can Delhi manage more than that?