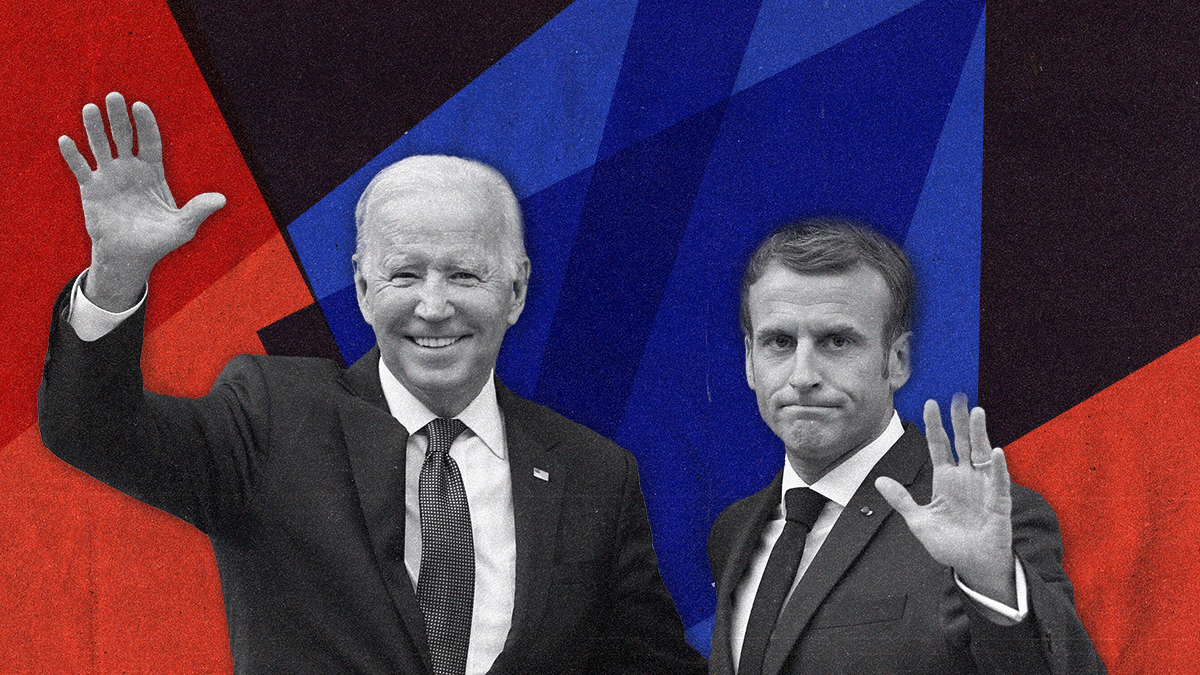

French President Emmanuel Macron is in Washington, DC, for an official state visit, the first world leader given that honor since President Joe Biden moved into the White House nearly two years ago.

Marked by military processions and fancy dinner parties, a state visit is essentially the greatest expression of “friendship” between two countries.

Biden and Macron, both known for public displays of affection, will surely go to great lengths to demonstrate that US-French relations are warmer than ever. But behind the scenes, the two leaders will have to hash out a series of thorny issues.

Macron’s already winning. While Macron is hoping to secure certain material gains, the invitation itself is likely already deemed a win by the French president, who has long been trying to carve out his place as the de facto leader of Europe.

To be sure, the competition isn’t stiff: The leader of a degraded Britain was hardly going to get the star treatment from the White House – nor was German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Angela Merkel’s wildly underwhelming successor.

What’s on the agenda?

Relatively straightforward: Reaffirming the transatlantic alliance and a coordinated Ukraine policy

The US and France have come a long way since Sept. 2021, when Macron briefly withdrew his ambassador from Washington after the AUKUS debacle, where the US froze Paris out of a crucial Asia Pacific security pact with Australia and the UK.

But since then, the US and France – leading the broader European Union – have exhibited a resilient partnership in an effort to isolate Russia and bolster Ukraine. Despite some divergent economic and strategic interests, the EU and US agreed early on to hit the Kremlin with coordinated coercive economic measures, while also presenting a united front on the diplomatic stage. Indeed, Biden and Macron will want to highlight this unity for Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin watching at home.

However, Biden and Macron have at times seemed to offer conflicting visions of an eventual endgame in Ukraine. While Paris previously called for dialogue with Russia to end the war, Biden has mostly reiterated Kyiv’s view that a settlement will only be reached once Russia withdraws from all Ukrainian territory.

Still, what leaders say in public is often very different from admissions made behind closed doors, and this multi-day summit will give Biden and Macron an opportunity to talk candidly about their views of a lingering conflict that has sent the global economy into a tailspin.

What’s harder to fix?

Made in America vs. Buy European

The EU – and France in particular – has made no secret of the fact that it abhors the Inflation Reduction Act, a key component of Biden’s legislative agenda that includes tax breaks for Americans who purchase electric vehicles made from parts manufactured only in North America. Decrying America’s protectionist policies, which he says discriminate against Europe’s robust auto industry, Macron has called for subsidy loopholes for the EU resembling those given to Mexico and Canada.

But Clayton Allen, a US expert at Eurasia Group, says that remains a pipe dream. “There is no room to extend the same exceptions granted to Mexico and Canada without new legislation,” Allen says, adding that “there is no appetite to pass that legislation in the lame duck [session],” or to do so in the next Congress.

Biden, for his part, “has no real wiggle room on the provisions of the IRA itself,” Allen adds.

Indeed, this sticking point has caused Paris to push its own “Buy European” agenda – a move aggressively backed by Berlin – with Macron calling for Europe to pass its own subsidy package to safeguard key industries.

Still, both Macron and Biden will be keen to stave off a transatlantic trade standoff that could deepen the global financial crisis. Rather, Macron will be trying to feel out how the US might respond to reciprocal protectionist measures.

Energy wars. While energy-dependent Europe is bearing the brunt of Western efforts to transition away from Russian energy exports, the US has in fact benefited from the global energy flux. Indeed, in the first half of 2022, the US surpassed Qatar and Australia to become the number one exporter of liquified natural gas, in large part due to the EU and UK having boosted their LNG imports to offset dwindling supplies from Russian pipelines.

With the EU feeling the pain, Macron has called on the Biden administration to pressure US gas companies to lower prices. The White House, for its part, says that its options are limited, noting that increased LNG prices are largely a result of the US Federal Reserve’s efforts to tackle inflation, which have made US exports more expensive for everyone. In reality, there’s little the Biden administration can do: High global demand for LNG is pushing prices up, including domestically. Indeed, some US lawmakers have even called for export limits on US LNG, but the Biden administration isn’t going for it.

Still, Macron isn’t buying it and accuses the White House of a “double standard” on energy and trade policy.

France and the US: et maintenant?

Despite all the tough talk, European – and French – “political preferences will be to maintain transatlantic unity over the Ukraine war and avoid a trade spat with the US,” says Mujtaba Rahman, Europe Managing Director at Eurasia Group. Indeed, Uncle Sam seems to be in a strong bargaining position.