Afghanistan frustrated nineteenth-century British imperialists for 40 years, and ejected the Soviet army in 1989 after a bloody decade there. And though American and NATO forces ousted the Taliban government in 2001 over its support for al-Qaeda, there's no good reason for confidence that nearly 20 years of occupation have brought lasting results for security and development across the country.

But… could China succeed where other outsiders have failed – and without a costly and risky military presence? Is the promise of lucrative trade and investment enough to ensure a power-sharing deal among Afghanistan's warring factions?

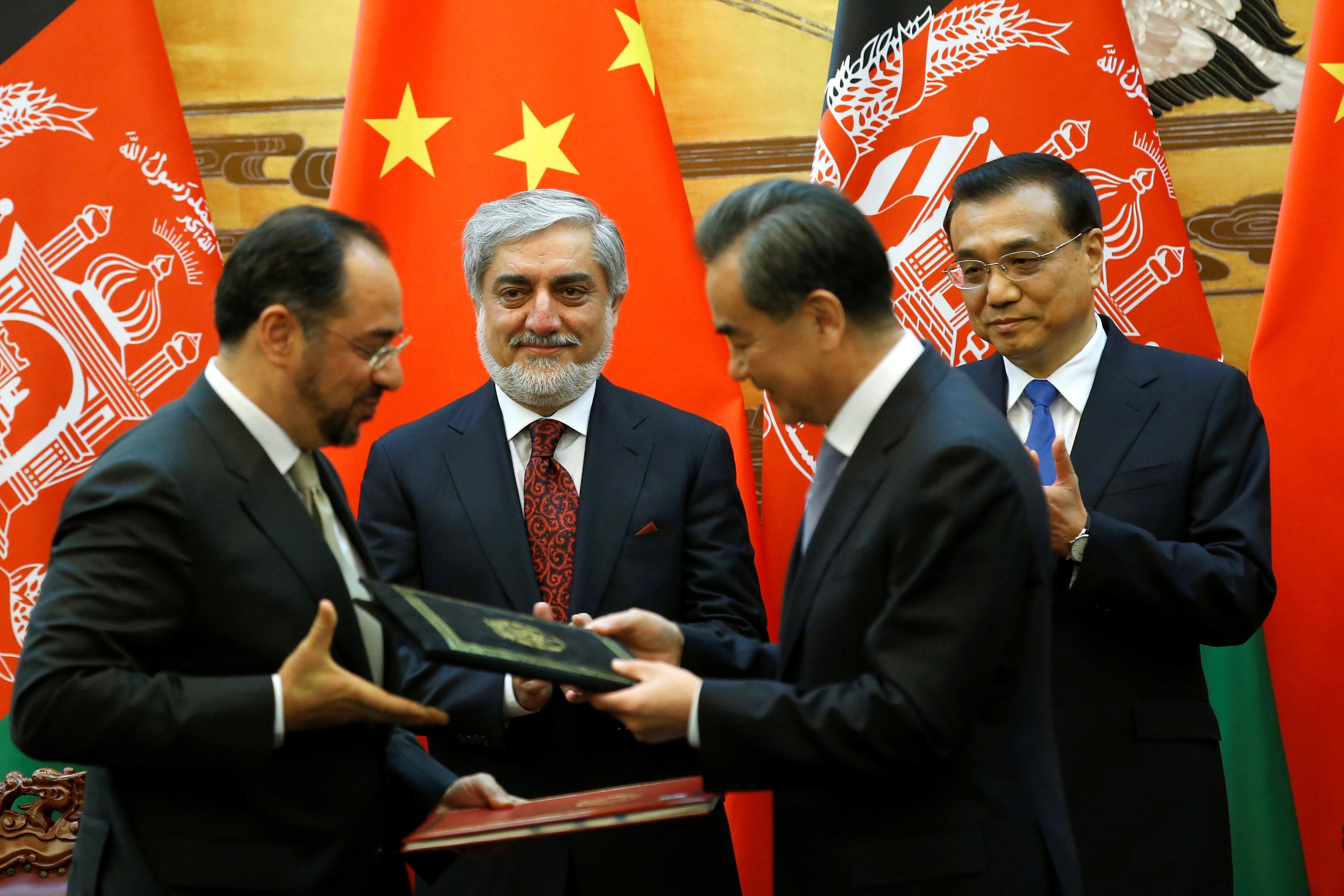

In recent years, the Chinese leadership has actively engagedboth the Western-backed government in Kabul and — given the likelihood they will eventually regain some degree of political power — Taliban fighters, in hopes of ending the never-ending conflicts that have long made Afghanistan ungovernable.

China has good reason to become more deeply involved. Afghanistan shares a short border with China's mainly Muslim Xinjiang region, and Beijing has long feared that instability in Afghanistan, heightened as the US and NATO prepare to withdraw troops, might allow Uighur separatists to use Afghan territory as a base for military operations. China also sees Afghanistan as an arena in which to promote stronger commercial and security ties with its Pakistani ally and gain advantage on its Indian rival.

Most importantly, Afghanistan offers major new economic opportunities for China via potential expansion across Afghan territory of China's Belt and Road infrastructure development project. Beyond the interest of Chinese companies in its mineral wealth, Afghanistan is China's direct overland path to the Middle East. It could also become part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a project of central economic and geopolitical importance for Belt and Road.

Deeper Chinese involvement might bring all kinds of good things for Afghanistan. All of the country's factions know China has staying power and a willingness to spend that others won't match. If China can persuade Afghanistan's government, the Taliban leadership, and local warlords that a sustainable power-sharing deal might make them all rich, it could bring a degree of stability that no foreign occupier can. Belt and Road could provide badly-needed infrastructure and the trade and investment opportunities that come with them.

And that's great… unless you're an Afghan who needs outside powers to try to force powerful locals to respect your rights. As we've written in the past, Afghanistan's women in particular face a precarious existence in a world where the fundamentalist Taliban exert major influence. Women and girls stand to lose significant gains in health and education made over the past two decades if Taliban promises to preserve them prove empty. Whatever high-minded rhetoric is written into diplomatic deals between China and Afghan factions, protections for human rights inside Afghanistan will never be a Chinese priority.

Or maybe it's all a mirage. Before China commits to big long-term investments — economic, political, and theoretically military if Chinese assets are threatened — its leadership must calculate whether engagement is a sustainable strategy. What if Afghan power brokers eventually decide they'd rather fight over spoils than keep the peace in their common interest? What if Taliban leaders can't control every Taliban faction? What if mounting debt, for both Pakistan and Afghanistan, make expanded regional infrastructure investment too risky?

Over the years, China's leaders have seen Britons, Europeans, Russians, and Americans stuck in Afghanistan without an exit strategy. Those are mistakes no one in Beijing is eager to repeat.