What's the real scope of online disinformation these days? How is it impacting US elections? And even more importantly, what can we do to curb fake news?

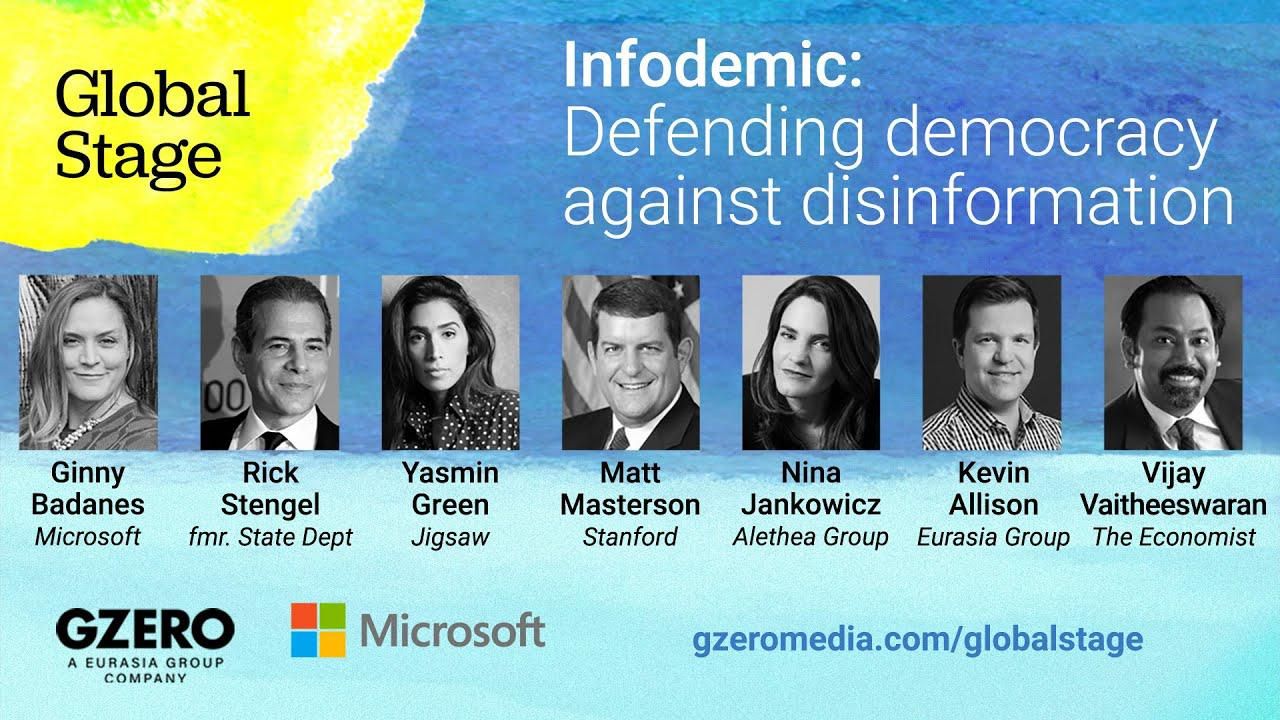

Experts from Microsoft, the Aletheia Group, Jigsaw, the Stanford Internet Center, Eurasia Group, and a former US government official shared their views during a Global Stage livestream conversation entitled Infodemic: Defending democracy against disinformation.

Although it's hard to measure exactly how much disinformation is out there, the Alethea Group's Nina Jankowicz says the scope of the problem has clearly grown recently. "We have moved from seeing foreign actors meddling in our elections to kind of a constant bombardment of our informational ecosystem, not just from foreign actors, but from homegrown disinformers as well." What's more, she adds, disinformation travels as far and as fast as it does nowadays thanks to social media, where "the most engaging content is the most enraging content."

In an poll conducted before the conversation, 54 percent of respondents said those who create fake news are the most responsible for the problem. For Ginny Badanes, senior director for Democracy Forward at Microsoft, the problem starts with those who create it, yet ultimately governments, companies and individuals all share the burden. And she's more interested in what we can do to respond.

Part of the solution may lie with tech companies, who say they can regulate themselves to curb disinformation. Sure, but former US State Department official Rick Stengel believes they should be on the hook as publishers. "Not only are they publishers; they're by far the biggest publishers in the history of the world by an exponential margin." Stengel thinks there's even US bipartisan consensus, although each side wants the same thing for different reasons.

The impact of disinformation on US elections is another pressing issue, especially after the events of January 6. Matt Masterson from the Stanford Internet Observatory says that US elections officials have always persuaded losing candidates that they've, ahem, lost, but it's worse because there's a new paradigm. Candidates that won't accept defeat regardless of the margin or evidence of fraud, he explains, are undermining trust in the system — and election officials are ill-equipped to deal with this problem.

As for whether social media companies made the right call by de-platforming Donald Trump for the US Capitol insurrection, Jigsaw's Yasmin Green points out that such moves can have the unintended consequence of people censored over hate speech going to alternative sites that can "exceed the tipping point" on extreme online speech. Major platforms have the absolute right to keep users safe, she says, but should think about mitigating that harm before canceling anyone.

Finally, what'll be the real-world impact of rising online disinformation? For one thing, Eurasia Group's Kevin Allison says we should brace for more violence driven by fake news in countries like India. For another, disinformation is already reversing the trend seen with the Arab Spring: social media no longer helps oust authoritarian regimes, but rather gives them a tool to entrench themselves in power by spreading disinformation.