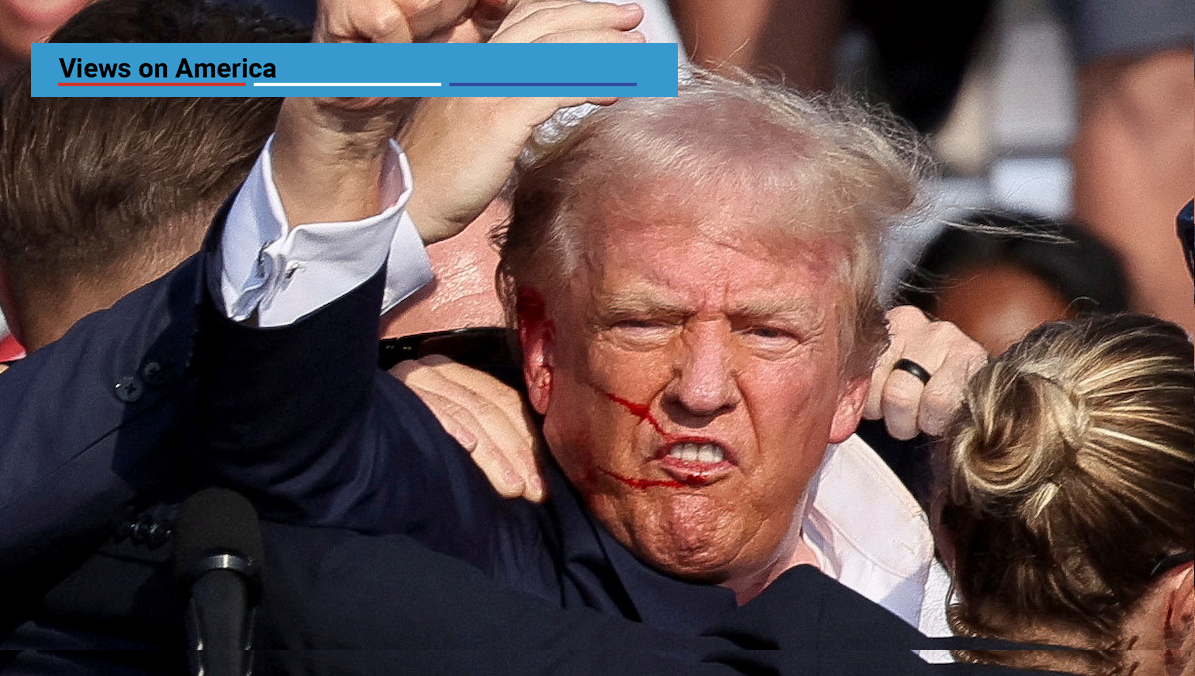

The brazen assassination attempt on former President Donald Trump this weekend has pulled from the shadows an inevitable implication of the country’s polarization: the risk of political violence. In this consequential US election year, with questions of institutional legitimacy hanging in the air, misinformation flooding social media, and worries about the fitness of at least one of the candidates, we have now been alerted to how real the threat of violence is for the months ahead.

Elections offer voters an opportunity to express something fundamental about what they expect from their government. This is at least the theoretical underpinning for conducting elections. But in each election, losers also have a responsibility. At its core, democracy is a system in which groups lose elections. Votes are held, results are counted and respected, and turnovers take place. Losers consent to being losers in any given election cycle because they believe they will have the opportunity to be winners in the future.

If, however, the institutional framework does not allow losers to become winners later, the system’s legitimacy erodes. Losers may withdraw their consent and pursue alternative strategies to access power. Sometimes this leads to boycotting elections, but sometimes the strategy is the use of force.

When winners repeatedly win and losers repeatedly lose, or if winners are perceived to repeatedly win and losers to lose, ballots may be replaced by bullets. In fact, according to data from the National Elections Across Democracy and Autocracy Dataset, in more than 4,000 global elections between 1945 and 2020, just under 19% of them involved significant violence. Nearly one in five elections over the past 75 years turned violent. Already in this pivotal election year, we have seen violence in the run-up to elections in Senegal, Pakistan, South Africa, Mexico (at historic rates), and France.

In the US, grievances that have been stoked around the legitimacy of the system and how well it is serving voters, travel through the existing fault lines in American politics – particularly political party identification – activating them further. It is now a near-truism that there is little common ground between the two political sides, and the gap is widening.Survey data from 2022 and 2023 has repeatedly found that a wide swath of the US population believes the system is rigged, and as much as a quarter of those polled agreed that it may soon be time to take up arms against the government. In 2021, these realities culminated in the Jan. 6 storming of the US Capitol. In 2024, this blueprint heightens the likelihood of civil unrest and violence across the US in the lead-up to and, depending on the outcome, after the election.

The name Thomas Matthew Crooks will now go down in the annals of US history alongside John Hinckley Jr. and Lee Harvey Oswald. While very little is currently known about what motivated Crooks’ attempt, lone-offender terrorism has become all too common. It speaks to a broader thread of radicalization that has emerged from US polarization – as political parties no longer speak to the same set of facts and individuals find themselves moving towards the extremes.

“Lone actors are difficult to detect and disrupt because of their lack of affiliation,” according to the2024 US Intelligence Community’s Annual Threat Assessment. “While these violent extremists tend to leverage simple attack methods, they can have devastating, outsized consequences.”

Yet it would be a mistake to focus too narrowly on Crooks’ character or political affiliation in attempting to make sense of the current US political climate. The polarization, the movement to the poles, the rising radicalization – are not just left (including ecological or animal-rights extremism, anarchists) or right (including racially or ethnically motivated extremism) problems. They are brewing on both sides of the aisle, especially as the center has become hollowed out.

When Trump was reported to have shouted “Fight” after being pierced by a bullet on Saturday, he was being heard. His message resonated with those who want to see him be returned to the White House in November, and those who just as desperately want to see him lose.

Security will be stepped up at rallies, this week’s Republican National Convention, August’s Democratic National Convention, and across all campaign stops. But as grievances grow, as fight talk and candidate fitness persist, so too will the shadow of political violence.

Lindsay Newman is the practice head of Global Macro, Geopolitics for Eurasia Group and is based in London. She writes the Views on America column for GZERO.