It's been fifty years since the United States declared one of the costliest wars in its history — a trillion-dollar campaign waged at home and abroad, which continues to grind on today.

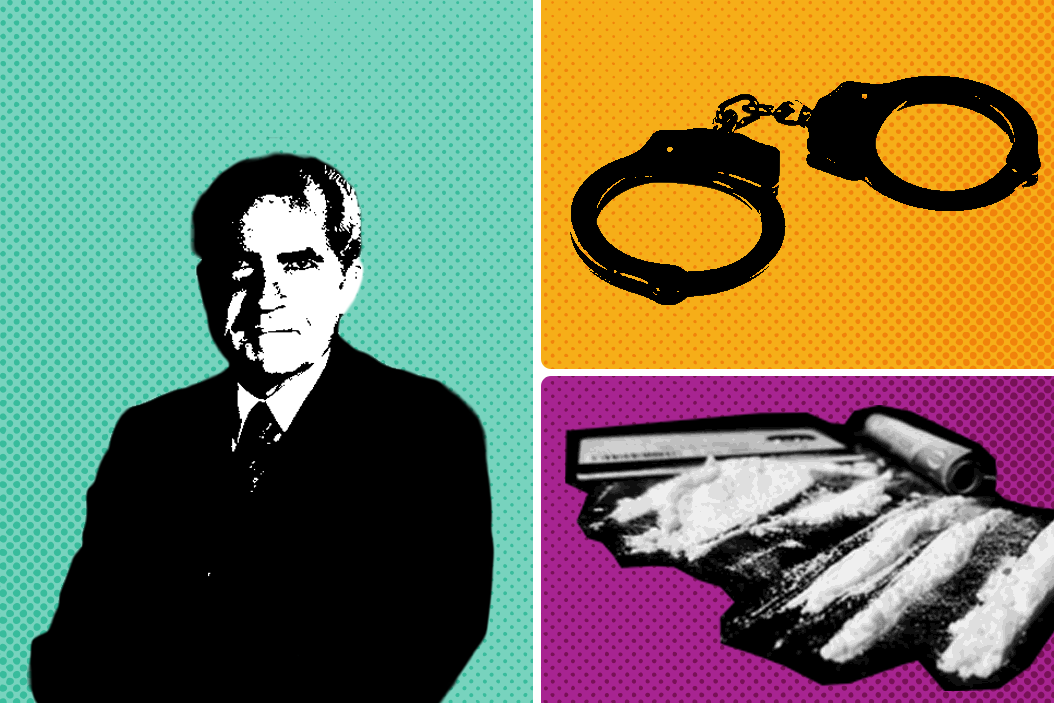

In June of 1971, President Richard Nixon, alarmed by the rise of permissive hippy culture and drug use, unleashed what would become known as the "war on drugs," a tough-on-crime approach that melded law enforcement, military action, and a public messaging campaign that both scared and scolded.

Aiming to reduce American drug use, it severely criminalized consumption in the US, while attacking international cartels' capacity to produce and export illicit narcotics, in particular from Latin America.

Did it work? We take a look at three of the war's major "battlefields" today.

The producer: Colombia. In the 1980s Colombia became the center of the global cocaine trade, which helped fuel the decades-long conflict between FARC guerillas, drug cartels, paramilitaries, and the Colombian government.

In 2000, Washington and Bogotá inked the multibillion-dollar Plan Colombia, in which the US trained and equipped Colombian soldiers to crush militants and quash the drug trade. To its credit, Plan Colombia helped force the FARC to negotiate a landmark peace deal in 2016 — but there has been no discernable success against drugs. Coca cultivation is near all-time highs, vastly surpassing levels seen even during the heyday of Pablo Escobar. And Colombian authorities are still making record cocaine busts.

The political problem is that the government hasn't met pledges to help farmers replace coca crops with legal ones. Doing so would mean providing security and economic opportunity in remote regions where the FARC dissolved but narcos filled the vacuum. Instead, the state has focused on US-backed eradication programs: wrecking coca crops either with environmentally-hazardous aerial spraying or, more recently, sending troops in to tear up coca fields, plant by plant. The trouble is, it doesn't work. Congress found in a 2020 report that eradication has produced "dismal results" -- it creates tension between farmers and the state, without diminishing coca cultivation for long.

If the 2016 peace deal is to have any meaning at all, this circle still needs to be squared. In Colombia, the war on drugs is still an obstacle to peace.

The middleman: Mexico. After US feds in the 1980s busted up the Caribbean transit hubs linking Andean producers and American consumers, overland routes through Mexico took off. By one FBI estimate, some 93 percent of drug flows from South America to the US now go via Mexico. These routes are controlled by the murderous and mind-bogglingly well-armed Mexican cartels that effectively run huge swaths of northern Mexico themselves today. Despite some joint US-Mexico successes, like taking down notorious kingpin El Chapo in 2014, the cartels are as powerful as ever.

What's more, cooperation between the DEA and Mexican officials has broken down under the administration of Mexico's prickly nationalist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

All of this has contributed to Mexico's soaring homicide rate, one of the world's highest. And that's a big problem for López Obrador. He was elected in 2018 partly on pledges to tackle the violence — but so far his "hugs not bullets" approach has yielded more lead than love.

In sum: the US war on drugs has failed to cut the enemy's biggest supply chain.

The consumer: the United States. "Just say no," former US First Lady Nancy Reagan told us. This sizzling egg is your brain on drugs, we learned. And still, decades later, rates of illegal drug use -- of all kinds -- remains high and rising.

Meanwhile, a raft of laws from the 1980s and 1990s -- some written by then-Senator Joe Biden -- heavily criminalized drug possession, causing the prison population to explode. That helped to make US incarceration rate the highest in the entire world. Black and Latino Americans have suffered disproportionately: drug convictions are more frequent and sentences harsher than for whites, though drug use rates are similar across racial groups.

But the politics are shifting. More than 80 percent of Americans — of both parties — now say the war on drugs has failed, and two-thirds believe it should end. A big majority favors decriminalization of drug offenses.

So far, more than half of US states have decriminalized small amounts of marijuana for personal consumption, and Oregon has done the same even with harder stuff. One of the thorniest debates now is how to ensure that profits from legal drugs go towards helping the communities of color ravaged for decades by drug enforcement.

And on Tuesday the Biden administration -- taking a Trump-era criminal justice reform even further -- endorsed an important bill that would finally eliminate disparities in sentencing between powdered cocaine, a more elite drug, and crack, whose generally-poorer (and Blacker) users have suffered harsher punishments for decades.

Still, the US pours billions into drug-oriented law enforcement annually. A drug arrest is made every 23 seconds, activists say. And overdose deaths have more than tripled in the past twenty years amid a raging opioid crisis kickstarted not by distant cartels, but by American drug companies, including those owned by the now-disgraced Sackler family.

The last line (so to speak): After 50 years, the war on drugs has not, by any reasonable standard, been won. Is there a better way? Let us know here

.