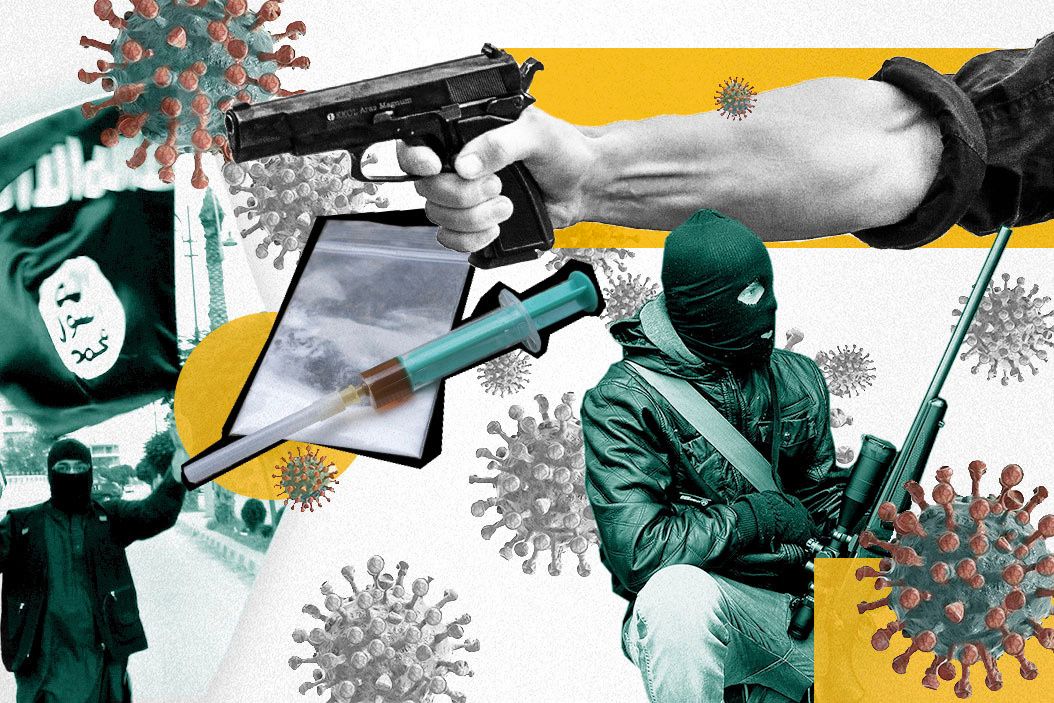

For much of the world, the rapidly expanding coronavirus pandemic is the worst global crisis in generations. Not so for terrorists, traffickers, and militant groups.

Efforts to fight coronavirus are diverting government attention and resources away from militants and gangs, creating huge opportunities, particularly for transnational terrorist groups who thrive in vacuums of security and political power, says Ali Soufan, founder of the Soufan Group, a leading authority on global terrorist organizations.

ISIS, for example, has recently called on its followers to intensify their jihad against governments in the West and in the Muslim world, particularly in Iraq. (Though they also issued a travel advisory against heading to Europe right now, which we imagined here.)

The jihadists of Boko Haram have stepped up strikes against weak governments in West Africa. And even as Iran grapples with one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in the world, its Shia proxies inside Iraq are continuing to attack US bases there as Washington withdraws troops from the country over coronavirus concerns.

What's more, the economic fallout of the crisis will also create good opportunities for bad actors. Coronavirus-related lockdowns and trade interruptions could plunge as many as half a billion people into poverty, according to a new Oxfam study. That's a godsend for groups that prey upon societies' most vulnerable and desperate people.

"This pandemic is worsening factors that lead to trafficking, like lack of education, violence, unemployment, and poverty" says Agnes Odhiambo, who follows human trafficking in Africa for Human Rights Watch.

A similar dynamic is at play in Italy, according to researchers from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Quarantines and border closures make it harder for Italian criminal organizations to conduct their usual business of trafficking and smuggling – most of which goes through legal border crossings anyway – but they are set to make a killing by loan sharking to nearly bankrupt businesses as lockdowns ease.

Still, some militants are on the public health frontlines themselves. Groups that control large swathes of territory of their own – say, Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, or the Houthis in Yemen – are now on the hook for dealing with COVID-19 themselves, if it comes. These groups now face "the same demands and requirements that a state actor would face," Robert Malley, the president and CEO of International Crisis Group told GZERO. Hezbollah, for example, recently mobilized some 25,000 health care workers to tackle the coronavirus outbreak. (No word on how much personal protective equipment it has.) A world away, the powerful drug gangs of Rio de Janeiro have assumed responsibility for quarantines in the city's hilltop favelas, where the Brazilian government has little sway. The gangs of El Salvador, one of the most violent countries on earth, are doing the same, to dramatic effect.

The ceasefire silver lining. In some cases, the challenge of dealing with coronavirus may open up fresh opportunities for peace. In late March, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres called for armed groups around the world to lay down their arms so that governments and insurgents alike could focus on stopping the pandemic. Most have ignored that plea, but some have listened.

In Colombia, the ELN, the largest remaining leftist guerilla insurgency in the country, declared a unilateral ceasefire for the entire month of April. In the Philippines, the government and communist guerillas declared a coronavirus ceasefire in a decades-long conflict that has killed more than 40,000 people. One of the smaller Anglophone separatist militias in Cameroon has done the same. The warring gangs of South Africa's Cape Town have declared a truce.

And earlier this week, the Saudi-led coalition fighting the Houthi rebels in Yemen announced a unilateral two week ceasefire. Tenuous though it may be, it's still the first of its kind in a five-year civil war that has created the world's worst humanitarian catastrophe. In all these cases, it's the threat from coronavirus that has stopped the fighting, at least for now.

Bottom line: It will be a long time before governments and international institutions can dial back their focus on COVID-19. In the meantime, the coronavirus will create huge opportunities for groups that exploit vulnerable people and vacuums in state power.