Next Tuesday marks the 40th anniversary of Iran's revolution, the moment when religious clerics overthrew a monarchy that had ruled that country for 2,500 years and created the world's first Islamic republic. It's a moment that remade Iranian society, realigned the politics of the Middle East, and transformed Iran's relations with the West.

To understand what Iran's revolutionaries were rebelling against, we begin a generation earlier. In 1953, a Cold War-inspired CIA-backed coup toppled the elected government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh to restore a monarchy led by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Over the next 26 years, Pahlavi promoted both economic modernization and intense political repression.

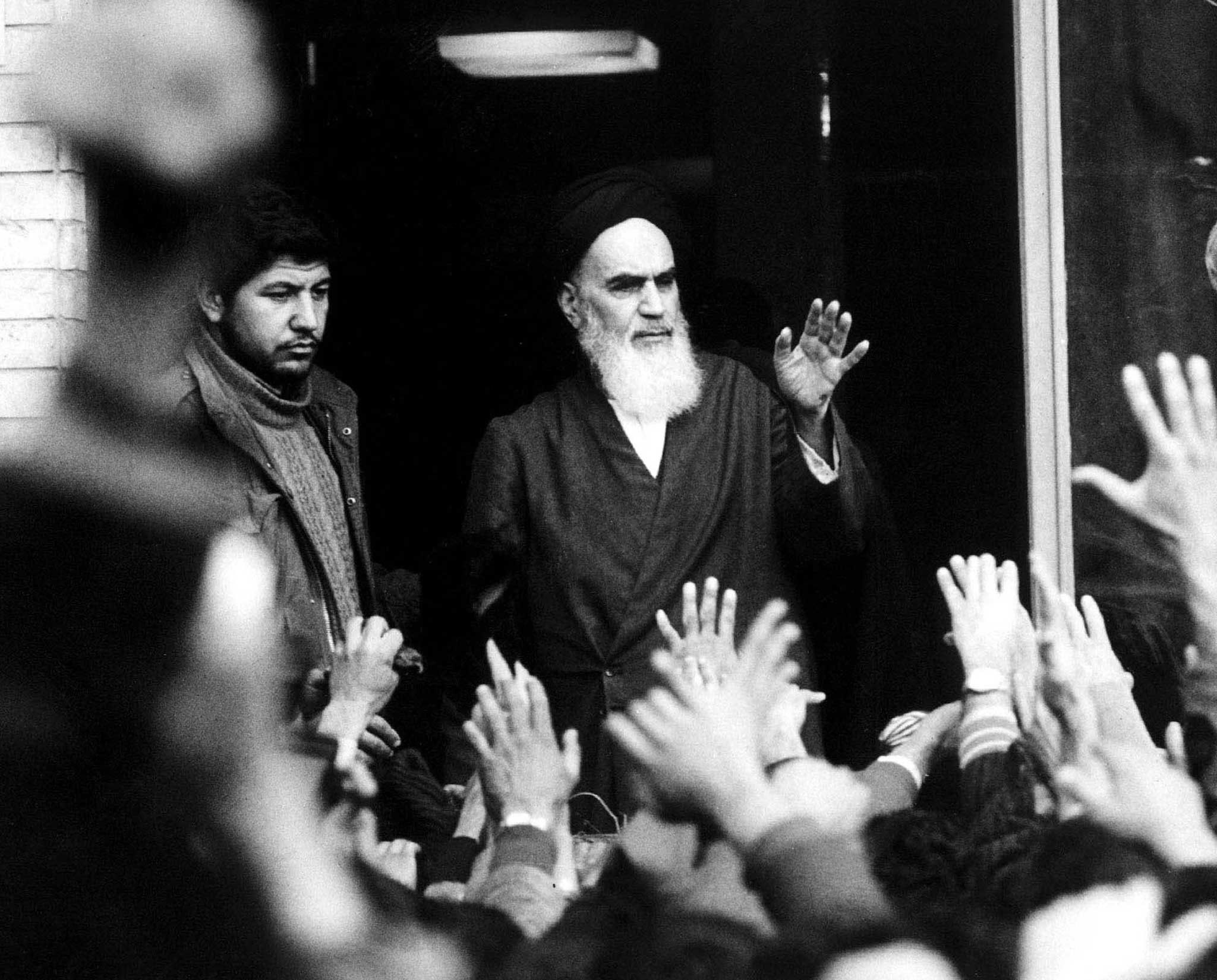

In 1979, opposition groups sensed an opportunity to take him down. A motley assortment of Marxists, nationalists, religious conservatives and student groups, fueled by audiotaped messages from the exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, launched widespread strikes and protests that pushed Pahlavi from his throne. The charismatic Khomeini then returned to Iran from France and began to consolidate power, in part by jailing and executing thousands of people.

The revolution's primary impact:

Shifting alliances: After the Jimmy Carter administration accepted the exiled Shah for medical treatment in the United States, Iranian students seized the US Embassy in Tehran and held 52 Americans hostage for 444 days. Hostility between the former allies has never really abated.

Iran's revolutionary export: The newly formed Islamic Republic then worked to spread its unique brand of conservative religious politics across the Middle East by supporting Shia militias, like Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hashd Shaabi in Iraq.

Saudi fear: The Saudi royal family, terrified by the toppling of the monarch next door and anxious to isolate a rival for leadership of the Islamic world, in 1981 founded the Gulf Cooperation Council, an alliance of Arab states, in part to isolate Iran. At home, Saudi royals launched a bid to bolster their Islamic credentials and placate religious conservatives by closing movie houses, banning concerts, and imposing strict new rules against the adoption of other Western customs.

Saddam's attack: Saddam Hussein, the secular Sunni leader of Iraq, feared Iran's revolution might inspire the Shia majority within his own country to rise against him. In response, and with the support of the US and Arab world, he waged an eight-year war on Iran that killed more than one million people.

Four decades later, Iran's revolution has a complex and contradictory legacy.

- Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the country's supreme leader since Khomeini's death in 1989, bases his right to rule on a revolution that more than 75 percent of Iran's 83 million people are not old enough to remember.

- Iran is a democracy trapped inside a theocracy. Its politics are far more complex and represent a far broader diversity of views than can be found inside many of its Arab neighbors. It holds genuinely competitive elections, but its candidates for office are selected by a small group of unelected clerics and lawyers.

- The Islamic Republic has a long history of brutally suppressing protests, but large public demonstrations remain common. For example, religious authorities continue to impose rules on female dress, yet Iranian women protest these restrictions in the streets and online.

- Anti-Western anger remains an essential element of Iran's political culture, but the Trump administration's decision to withdraw the US from the Iran nuclear deal has incentivized Iran's government to pursue closer relations with the European powers who signed that agreement and oppose Trump's move.

In Iran today, a moderate president, Hassan Rouhani, has seen his reforms undermined by both hard-line supporters of the Supreme Leader and President Trump's decision to reimpose US sanctions. Recession looms and inflation rises.

For now, the clerical establishment remains firmly in charge, but public frustration with economic hardship, a Supreme Leader who will turn 80 in July, and uncertainty over succession leave us to wonder: How many more birthdays can Iran's current leadership celebrate? Can the Islamic Republic continue to adapt in order to survive?