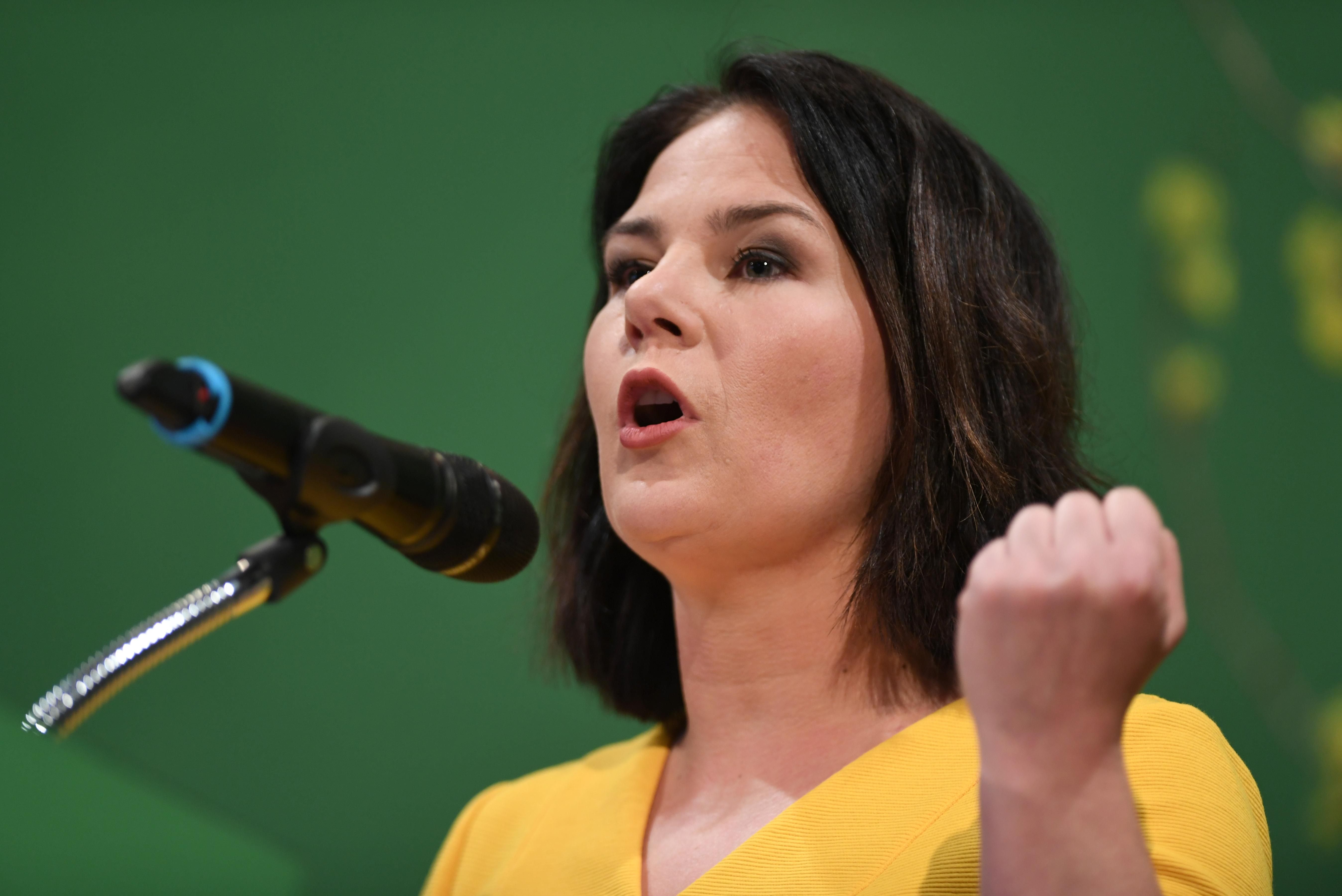

A Green Party-led government for the world's fourth largest economy?That's no longer far-fetched. As Signal's Gabrielle Debinski wrote last month, most current polls now show Germany's Greens in first place in federal elections set for September 26. And for the first time, the Greens have a candidate for chancellor. Annalena Baerbock is vying to replace Angela Merkel, who has led Germany for the past 16 years.

How have the Greens reached this point? A frustratingly ineffective COVID response, with on-again-off-again lockdowns, has undermined the governing center-right coalition's chief political selling point: a reputation for competent leadership. The ascendancy of climate change as a central issue across Europe, particularly for young voters, has helped too. Ironically, Merkel herself has helped mainstream the Greens with her own push in recent years against nuclear power and coal. A recent ruling on climate policy from Germany's Supreme Court has pushed the country even further toward emissions reduction commitments.

Thanks to Baerbock, the Greens may have real staying power. The party has a history of strong polling and weak election day performance. But this time, a decided lack of enthusiasm for center-right candidate Armin Laschet, who had to survive a strong leadership challenge from a more popular rival, is boosting the Greens' chances. This will be the first German election since 1949 in which the incumbent chancellor is not on the ballot, and Baerbock may appeal to voters who have supported Merkel more than they support her party.

More importantly, it would be a mistake to underestimate the Greens' 40-year-old standard bearer. The charismatic Baerbock isn't simply a made-for-television candidate. She's a detail-orientated expert on climate change and knowledgeable on foreign policy. A graduate of the London School of Economics, Baerbock speaks fluent English. She's already proven herself a gifted political strategist and bested Laschet in all recent head-to-head polls. But Baerbock is also the change candidate in a year that Germans may well want to turn the page on 16 years of center-right leadership.

A real shot at power has changed the Greens. Beyond their ambitious approach to climate policy, they've adopted a much more pragmatic foreign policy than in the past. A willingness to reach for votes from Germans who prioritize economic growth has moderated criticisms of China and Russia, for example. A respect for fiscal discipline led the Greens toward a restrained approach to financial aid for Greece during the Eurozone crisis.

Even if the Greens don't finish first in September, they're almost certain to be part of the next coalition government. Conservatives will have to offer substantive climate concessions to bring Greens into a partnership. In particular, the Greens want Germany to meet the Paris Climate Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by making all cars emission-free by 2030 and by raising carbon taxes. They also want to scrap a constitutional amendment that limits the government's ability to borrow to finance spending – a measure already temporarily suspended during the pandemic – in part to boost spending on green tech.

Do Germans really want change? It might depend on COVID's course. Laschet will offer himself and his party as steady hands. He will argue that Baerbock and the Greens have no idea how to run a government. But that case will be harder to make if the current government can't get Germans vaccinated and its economy on the road to recovery over the next 20 weeks.- Is it the Greens' moment in Europe? - GZERO Media ›

- Germany's floods make climate, competence top issues for election - GZERO Media ›

- German election campaign full of drama and uncertainty - GZERO Media ›

- Germany’s frenemy kingmakers - GZERO Media ›

- Germany’s frenemy kingmakers - GZERO Media ›

- Germany's next government taking shape - GZERO Media ›