October 06, 2021

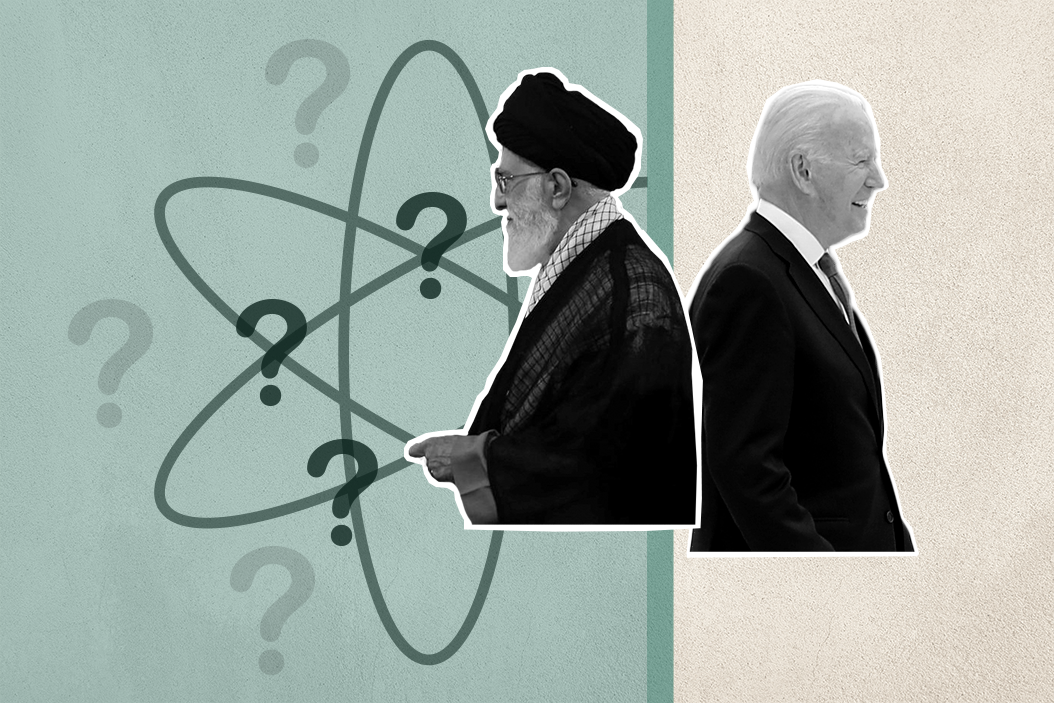

When then-candidate Joe Biden was vying to move into the Oval Office, he remained wishy-washy on several policy issues. But one thing was abundantly clear: rain, hail or shine, Biden planned to return to the Iran nuclear agreement negotiated in 2015 by his boss Barack Obama and nixed by anti-Iran hawk DJT.

But it takes two to tango, or in this case to tank a key diplomatic pursuit. The Iranians, who in the spring seemed gung-ho about the idea, are now slow-walking it, making a return to the nuclear deal in the near term seem very remote.

Background. After a three-year hiatus, Washington and Tehran agreed to return to the negotiating table (initially through intermediaries) earlier this year to figure out how to handle Iran's burgeoning nuclear project, and lift crippling US economic sanctions. Since the US abandoned the deal in 2018, Iran has been steadily upping its uranium enrichment, now bringing it close to levels needed to build a nuclear weapon.

Then in June, Iran hit the brakes entirely on negotiations while it waited for the dust to settle after holding elections. Iran's new President Ebrahim Raisi, a hardliner's hardliner, says Iran will return to the negotiating table at some point while still trafficking in extreme anti-American rhetoric, most recently during his international debut at the UN General Assembly.

Why isn't there a deal yet?

Iranian politics are not monolithic, nor are they one-dimensional. While supreme leader Ali Khamenei calls the shots, there are also other political forces at play.

Back in December, Iran's parliament passed a law mandating the ramping up of its nuclear program so long as US economic sanctions remain in place. Tehran has also played hard and fast with UN nuclear inspectors, suspending access this summer, saying that the international community should "trust" Iran to self- document its progress.

Moreover, another sticking point is that both the supreme leader and parliament want a commitment from Washington that the US won't reverse course on sanctions relief if there's a Republican president in 2024. Biden doesn't have the power to guarantee that, and the US Congress would never go for it either.

The US, for its part, is also grappling with a host of domestic concerns that have made it extremely hard for the Biden administration to soften its Iran stance. The Afghanistan withdrawal fiasco, infighting within Biden's Democratic party over his domestic policy agenda, and crises at the southern border have all caused the president's poll numbers to tank — so the last thing he can afford is a diplomatic snafu with a US adversary. Biden needs a clean win – fast – and negotiations with Iran will be slow, painstaking, and require compromises that could alienate some moderate supporters. It's a powder-keg issue when Biden needs a slam dunk.

Do the two sides even want a deal?

Tehran is talking a tough game, but the Iranians say they still want to return to the negotiating table at some point. But actions speak louder than words. For instance, the regime recently tapped Bagheri Kani, a vocal opponent of the nuclear deal and former negotiator under former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, to head talks when they resume. That surely reduces the likelihood of finding common ground in the near term.

This complicates things at home because the supreme leader and his allies are laser-focused on staving off a popular uprising as a result of broad economic decline in Iran and surging food prices. The political establishment needs to walk a very fine line because many Iranians see dialogue with the West as their way out of enduring economic hardship.

The Biden administration, for its part, doesn't want to be seen as reneging on a key policy pledge. But its trust in the process is certainly dwindling. Robert Malley, the US' point person on Iran, said reviving the accord is "just one big question mark," and there's little the US can do if Iran refuses to engage. The Americans want to revive the nuclear agreement, sure. But they don't want to be seen as caving to a rival's demands and pleading with Tehran to return to the table.

From Your Site Articles

- Can the nuclear deal with Iran still be salvaged? - GZERO Media ›

- The pros and cons of a nuclear program for Iran - GZERO Media ›

- The US can’t let Iran get any closer to nuclear weapons, says Iran expert Ali Vaez - GZERO Media ›

- Iran nuclear deal is dead - GZERO Media ›

- US-Iran World Cup sportsmanship amid political tensions - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: A tale of two Koreas with veteran Korea journalist Jean Lee - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: Do nuclear weapons keep us safe? An arms control expert weighs in - GZERO Media ›

- The Iran nuclear deal - GZERO Media ›

- Iran nuclear deal now a toss-up, says International Crisis Group expert - GZERO Media ›

- How the nuclear arms race went high tech - GZERO Media ›

- Should we still be worried about the nuclear threat? - GZERO Media ›

- Nuclear weapons: more dangerous than ever? - GZERO Media ›

More For You

- YouTube

In this Quick Take, Ian Bremmer addresses the killing of Alex Pretti at a protest in Minneapolis, calling it “a tipping point” in America’s increasingly volatile politics.

Most Popular

- YouTube

Who decides the boundaries for artificial intelligence, and how do governments ensure public trust? Speaking at the 2026 World Economic Forum in Davos, Arancha González Laya, Dean of the Paris School of International Affairs and former Foreign Minister of Spain, emphasized the importance of clear regulations to maintain trust in technology.

- YouTube

Will AI change the balance of power in the world? At the 2026 World Economic Forum in Davos, Ian Bremmer addresses how artificial intelligence could redefine global politics, human behavior, and societal stability.

Ian Bremmer sits down with Finland’s President Alexander Stubb and the IMF’s Kristalina Georgieva on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum to discuss President Trump’s Greenland threats, the state of the global economy, and the future of the transatlantic relationship.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.