"Italy got drunk on the idea of the European project and fell in love. But now people understand that we were better off before."

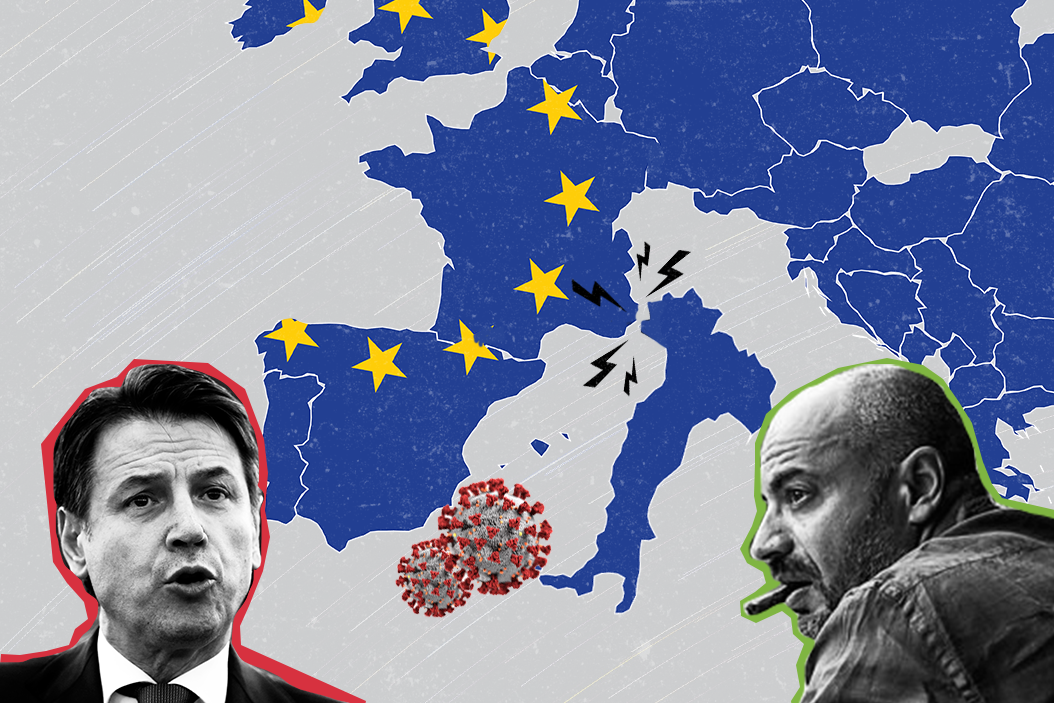

That's what Gianluigi Paragone, former journalist and senator of Italy's anti-establishment Five Star Movement, said in a recent interview, outlining why he's forming the rebellious Italexit party, hoping to revive the dormant debate over Italy's possible withdrawal from the European Union. Will the Italexit movement gain steam?

Italy's pain. Italy's pandemic experience has been a horror story. An early COVID-19 epicenter, it has now recorded more than 35,000 deaths, mostly in the northern Lombardy region where hospitals were overrun and doctors were forced to make gut-wrenching decisions about who lives and dies.

The economic pain has also been acute. Italy's economy, which has the second-highest public debt-to-GDP ratio in the EU, is set to shrink by at least 11.2 percent this year, according to the European Commission, the worst projection among all 27 EU member states. Its tourism-dependent economy is reeling as foreign travel has ground to a halt. (Tourism accounts for about 13 percent of Italy's GDP, while some 4 million jobs in Italy are attributable to tourism, the highest number of any country that Eurostat has collected data for.)

Making matters worse, poverty and inequality have long been surging in Italy, while upward mobility has sagged. Meanwhile, a fractious coalition government has failed to improve the lives of Italy's shrinking middle class. It's no surprise then that millions of Italians are frustrated, insecure, and worried about their futures.

This pessimism has helped far-right firebrand Matteo Salvini cut a dominant figure in Italian politics in recent years. Though his nationalist Lega party leads the polls, Salvini himself has moderated his views on the European project in recent months, creating a policy vacuum that Italexit advocates may seek to fill.

A populist's dream. Gianluigi Paragone was recently in London, meeting with Brexit mastermind Nigel Farage for some pointers on how to whip up support in Italy for a Brexit-style referendum. And he's not the only Italian trying to take up the Eurosceptic mantle. A mayor in the northern city of Verona has kick-started a petition for Italy to leave the EU, the first step in the complex referendum process, while Vittorio Sgarbi, an art critic and libertarian politician who served in former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi's government, is also pushing for a vote on Italy's withdrawal from the Union in the near term.

Seizing the moment. These anti-establishment office-seekers are capitalizing on a growing sentiment among Italians that the EU abandoned them at their darkest hour. When Italy's outbreak was surging in late March — hospitals were inundated and protective gear was scarce — Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte turned to Russia and China for medical supplies (though many turned out to be unusable) as the European bloc deadlocked over how to collectively respond to Italy's woes.

Europe's slow response riled an Italian electorate that has harbored resentment towards the European project for years because of the stagnation of living standards in that country. A poll conducted in April found that 70 percent of Italians have little or no trust in the EU, while 50 percent of respondents in a different survey said they favored leaving the bloc altogether.

The referendum process is complex. International treaties cannot be ratified (or nullified) by referendum in Italy. Euroscpetics, therefore, seem to be proposing a popular initiative bill to hold a referendum, which requires at least 500,000 signatures and approval by the Supreme Court of Cassation (the highest court of appeal) to be voted on by parliament. It's a convoluted procedure made more complicated by Italy's deepening political polarization, but the process could still empower Italy's populists whether a referendum is actually held or not.

The timing of the Italexit push is curious. Last week, the European Union reached a deal on a massive economic recovery plan, acquiescing to Rome's demand that its reeling economy get the lion's share of the relief funds, alongside Spain.

While this may have placated some Italians' concerns, disbursement of the funds could take up to two years, giving the Italexit camp more time to tap into mounting dissatisfaction with the EU. (One Italian poll already has the yet-to-be-launched party polling at a staggering 7 percent.)

The bottom line. An Italexit referendum will be hard to pull off anytime soon, but ardent Eurosceptics will try to use this anti-EU momentum to make a play for power.

More For You

Tune in on Saturday, February 14th at 12pm ET/6pm CET for the live premiere of our Global Stage from the 2026 Munich Security Conference, where our panel of experts takes aim at the latest global security challenges.

Most Popular

In this Quick Take, Ian Bremmer weighs in on the politicization of the Olympics after comments by Team USA freestyle skier Hunter Hess sparked backlash about patriotism and national representation.

In July 2024, Keir Starmer won the United Kingdom’s election in a landslide. It has been downhill ever since, with Starmer’s premiership sullied by economic stagnation, intraparty fighting, and a lack of vision for the country.