The world has its eyes on Vladimir Putin’s ambitions to retake former Soviet territory amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But remarkably little attention has been paid to another nation from which the USSR once seized land. Hint: it’s not a part of NATO.

We’re talking about Japan, which has a sovereignty dispute with Russia dating back to the final days of World War II over the Kuril Islands, located between the Japanese archipelago and the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia’s far east. Japan has been unsuccessful in trying to reclaim the islands ever since.

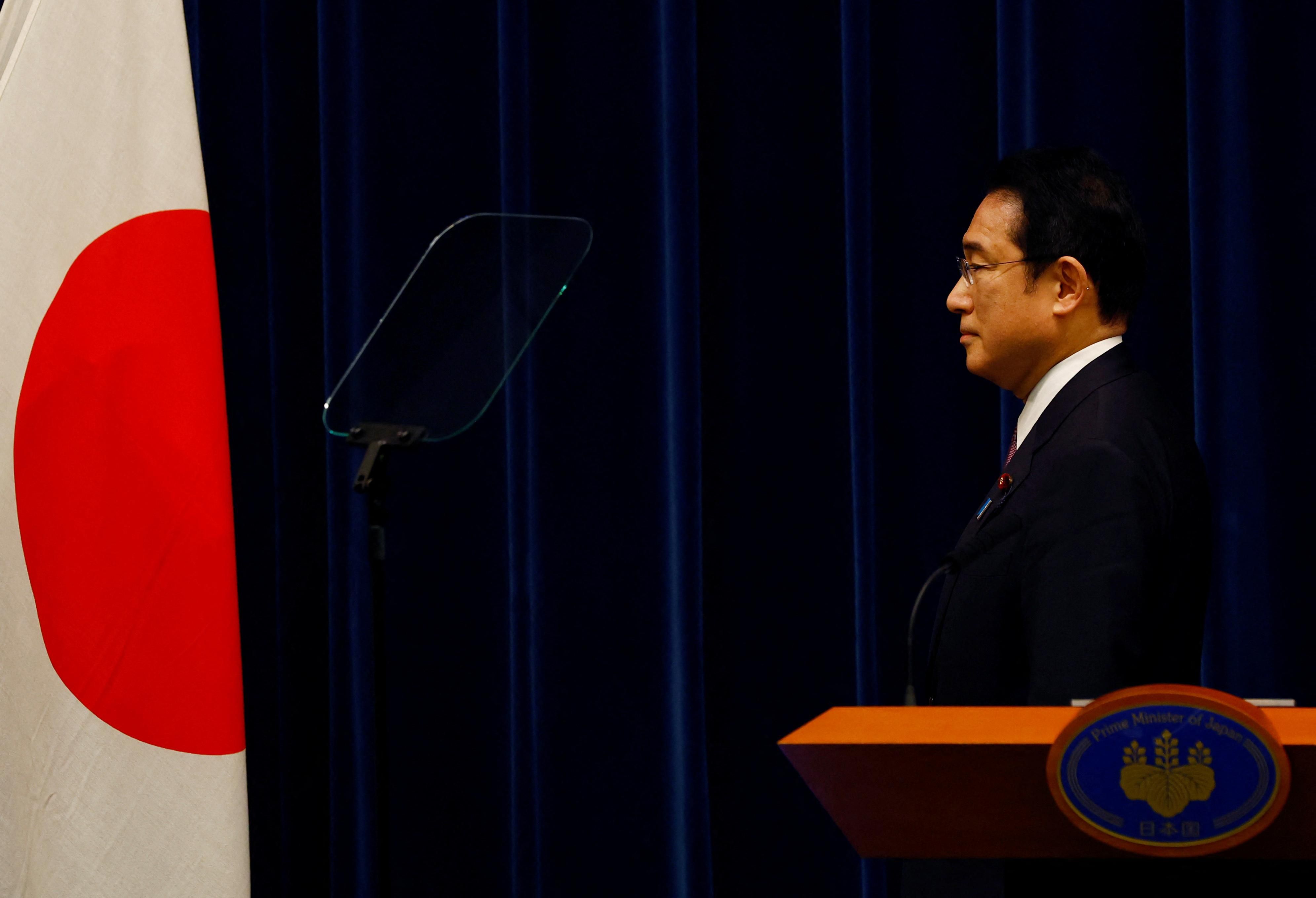

Japanese leaders have always done verbal gymnastics when talking about the Kurils to appease Russia, but now PM Fumio Kishida is fed up. He recently used unusually strong language to clarify that the islands indeed belong to Japan and are unlawfully occupied by Russia.

Moscow responded on Monday by suspending long-running peace talks with Japan, which has essentially given up all hopes of negotiating the return of the islands — at least as long as Putin remains in power.

What’s changed? The war in Ukraine, which has turned long-dovish Japan into a fresh defense and foreign policy hawk.

Two weeks after Germany reversed a decades-long ban on supplying deadly weapons to conflict zones in order to send arms to Ukraine, Japan — with a similar post-war pacifist constitution — made its own dramatic policy shift by dispatching (non-lethal) military equipment to Kyiv via the US military.

Japan also abandoned its traditional cautious approach to sanctions by backing US-led moves to cripple the Russian economy, and it could even join the US and others in banning imports of Russian oil and gas.

A risky move. Although Moscow is not a major trading partner for Tokyo, energy-hungry Japan still imports about 9% of its gas from Russia. “To cut that off is not easy,” says Eurasia Group analyst David Boling. The Japanese economy is already feeling the pinch from sanctions with, for instance, sky-high prices of sushi.

What’s more, Japan knows that the regional power that most stands to benefit from a Russia weakened by sanctions is the one they fear most: China, which has its own maritime sovereignty beef with Japan in the East China Sea.

All eyes are now on Russia’s energy-rich Sakhalin Island, just north of the Kurils. Most Western majors have pulled out of Sakhalin over Ukraine, but Japan is still involved in two oil and LNG projects there. Boling says Tokyo is worried that Beijing might swoop in for the leftover spoils if Russia nationalizes Japanese assets and sells them off cheap.

There’s also a domestic political angle. Kishida has long struggled to get out of the shadow of Shinzo Abe, Japan’s longtime former prime minister who stepped down in 2020 and is now more free to speak his mind in public despite still being an MP.

Since the Russian invasion, the influential Abe has been pushing his former top diplomat to the right on national security. He even called for Japan to consider hosting US nukes — a taboo issue in the only nation ever attacked with atomic weapons.

The Japanese PM, a soft-spoken bureaucrat with zero of Abe’s swashbuckling charisma, surprised many by pushing back against his former boss. Why? For one thing, he wants to boost his own already-high approval rating ahead of elections for the upper house of parliament in the summer. For another, the Japanese people overwhelming approve of sanctions against Russia and fear China may soon invade Taiwan.

“Kishida served as foreign minister under Abe — he gets foreign policy,” Boling explains. “He knows this crisis is unlike any other. He also knows that China increasingly represents a serious national security threat to Japan — and that what is playing out in Ukraine could happen in Japan’s neighborhood in the future.”