March 01, 2023

The US Department of Energy made unlikely headlines over the weekend when The Wall Street Journal reported that new evidence had led the agency to conclude with “low confidence” that the COVID-19 virus probably escaped from a Chinese lab. The DOE’s findings match up with the FBI’s, which point to an accidental leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology with “moderate confidence.”

This follows investigations by four other agencies plus the National Intelligence Council that concluded with low confidence that the virus spread naturally from animals to humans, possibly in a wet market in Wuhan. Other intelligence agencies, including the CIA, remain undecided, much like DOE was until recently.

The bottom line is we still don’t know how the pandemic got started. Both origin stories – natural transmission and laboratory leak – are scientifically plausible. The DOE’s report should lead us to update our beliefs slightly toward the lab-leak theory, but the score in the intelligence community is still 5-2 in favor of zoonotic transfer, and all but the FBI’s conclusions were reached with low confidence.

One thing we do know – and all agencies agree on this – is that the virus was not deliberately engineered and released by China as a bioweapon. We also know that Beijing systematically lied to the international community, the World Health Organization, and its own citizens about the virus, making the outbreak worse than it had to be. (Yes, those two thoughts are compatible: The Chinese government’s sketchiness can be easily explained by many reasons other than bioterror.)

But we will likely never get to the bottom of COVID’s true origins, precisely because China refuses to allow a proper investigation.

So … what more is there to say about this?

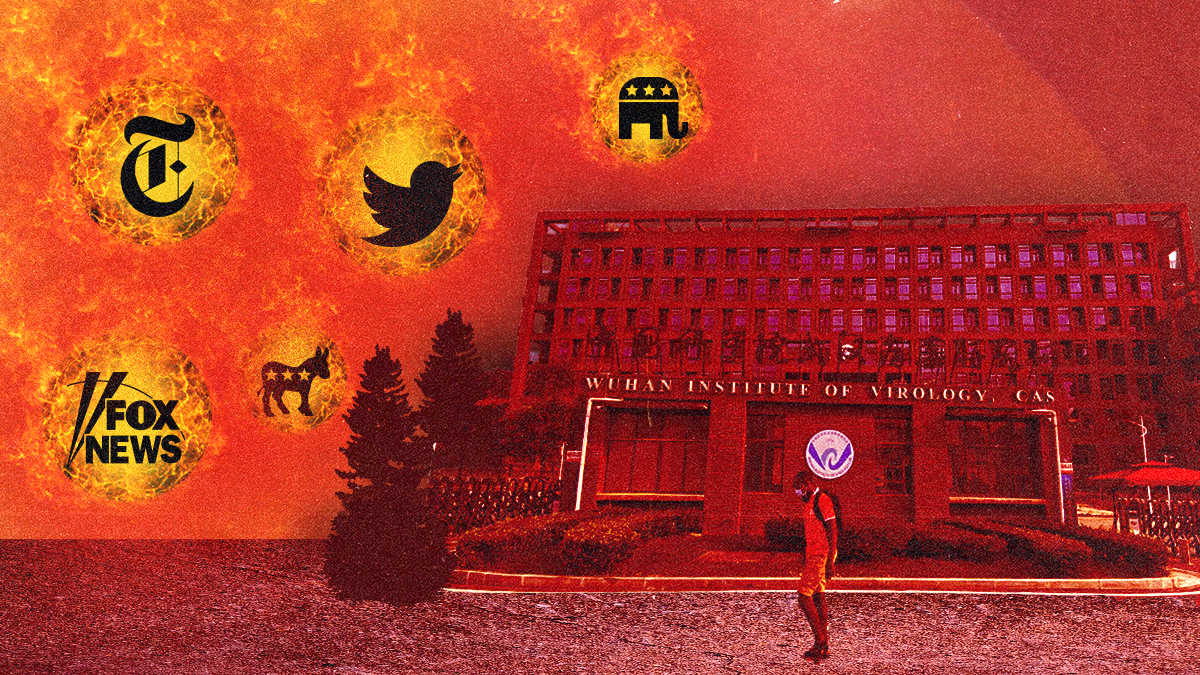

Well, I think there is an important lesson here about the politicization of science in the United States. Coming out as a believer in the lab-leak hypothesis would have gotten you banned from social media just two years ago. Today, multiple U.S. intelligence agencies consider it reasonable if not likely. What gives?

Uncertainty reigned supreme in the early days of the pandemic. Nobody knew how deadly the disease was, how easily it could spread, who was vulnerable to it, or how to protect themselves from it. Back then, the dominant narrative about the virus’s origins was that it had jumped from a bat to a human at Wuhan’s live-animal market.

But in February 2020, Republican Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton went on Fox News and raised the possibility that coronavirus may not have emerged naturally while accusing Beijing of a lack of transparency.

“We don’t know where it originated, but we do know we have to get to the bottom of that,” the senator said. “We also know that just a few miles away from that food market is China’s only biosafety level-4 super laboratory that researches human infectious diseases. We don’t have evidence that this disease originated there,” he clarified, “but because of China’s duplicity and dishonesty from the beginning, we need to at least ask the question to see what the evidence says, and China right now is not giving evidence on that question at all.”

Cotton’s message found a receptive audience in right-wing conspiracy theorists. Almost immediately, what had started as a perfectly legitimate question got spun into an unfounded story that the virus was a bioweapon deliberately engineered by the Chinese Communist Party for nefarious purposes. Some even went so far as to claim Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the face of the U.S. pandemic response, funded China’s biowarfare program.

Mind you, Cotton himself never said he thought COVID was an act of biological warfare. In fact, he called that possibility “very unlikely.” All he said was it was an open scientific question that called for further investigation, requiring access to evidence Beijing was refusing to provide.

And he was 100% right. COVID’s origins were (and still are) very much an open scientific question. And this question was especially hard to answer given the Chinese government’s (ongoing) obstruction.

But, inured to former President Donald Trump’s racist antics and the American right’s penchant for amplifying misinformation, Twitter scientists, pundits, and journalists in the mainstream media rushed to shout Cotton down, lumping his views in with those of the cranks.

They called any suggestion that the virus did not emerge naturally a “debunked conspiracy theory” motivated by an anti-China and anti-science agenda, even though the lab-leak hypothesis was neither a conspiracy theory nor had it been debunked. They dismissed the message not because it was wrong but because they disagreed with the messenger’s worldview and disliked some of his political bedfellows.

As it turned out, the fact that Cotton’s doubts may have been colored by his anti-China bias, or that others took his hypothesis too far, was irrelevant to the question at hand. And the media’s uber-confident proclamation of a fake consensus when the science was nowhere near settled did real harm, delegitimizing public health authorities and further eroding trust in science.

Why did otherwise smart, judicious, and well-intentioned journalists and scientists react so virulently – and, indeed, unscientifically – to the lab-leak hypothesis? Two words: politics brain.

The political environment was exceptionally charged back then. Partisan polarization had divided Americans into tribes bitterly pitted against each other. Citizens were constantly bombarded with conflicting information, and whether something was accepted as true or false depended as much or more on who it came from than whether it was actually true.

So when a vocal China hawk representing a political party hostile to science and comfortable with conspiracy theories raised questions about the prevailing narrative, the natural instinct of many in mainstream media was to push back. Because many of those who publicly raised questions about the virus’s origins were bad actors, the act of raising questions itself became an act of bad faith. That’s what politics brain does to us: It clouds our judgment and supercharges cognitive biases like groupthink, mood affiliation, and motivated reasoning.

There’s another lesson here. Yes, parts of the media and the scientific community were biased. Bias is human. Bias is inevitable. I can live with bias. But the bigger problem was the misplaced confidence.

One thing that annoyed me about Dr. Fauci – who I’ve gotten to know a bit and consider a dedicated public servant – was how certain he came off in some of his early communications on questions that he obviously wasn’t certain about. Now, people don’t like uncertainty, and science is hard. Sometimes it needs to be simplified for the public to understand. Fauci didn’t want to cede any ground that the anti-science crowd could exploit to sow doubt. I get that.

But all that false certainty ends up doing is delegitimizing science at a time when trust in objective truth and institutions of knowledge is at historic lows. It’s genuinely better to treat people with respect, explain the nuances, say “I don’t know” when you don’t know, and hope they’ll get it. That goes for the pandemic’s origins, vaccine effectiveness, long COVID, climate change, and many other areas of scientific inquiry.

When it comes to science, just … follow the science.

________________________________

🔔 Be sure to subscribe to GZERO Daily to get the world's best global politics newsletter every day on top of my weekly email. Did I mention it's free?More For You

Global conflict was at a record high in 2025, will 2026 be more peaceful? Ian Bremmer talks with CNN’s Clarissa Ward and Comfort Ero of the International Crisis Group on the GZERO World Podcast.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi isn’t necessarily known as the greatest friend of Muslim people, yet his own government is now seeking to build bridges with Afghanistan’s Islamist leaders, the Taliban.

French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, U.S. Special Envoy Steve Witkoff and businessman Jared Kushner, along with NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte and otherEuropean leaders, pose for a group photo at the Chancellery in Berlin, Germany, December 15, 2025.

Kay Nietfeld/Pool via REUTERS

The European Union just pulled off something that, a year ago, seemed politically impossible: it froze $247 billion in Russian central bank assets indefinitely, stripping the Kremlin of one of its most reliable pressure points.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.