December 15, 2021

It’s been a decade since Muammar Qaddafi, one of the world’s most eccentric despots, was ousted and killed in a popular uprising. But instead of enjoying a new democratic dawn, Libya has since spiraled into inter-factional conflict and chaos.

The country’s luck is supposed to change next week when Libya’s first democratic elections are scheduled to take place. But it now seems all but certain that the vote will be stalled — or scrapped altogether.

What’s the state of play in Libya, and why are so many external powers jockeying for power in this poorly understood country of 7 million people?

Background. Tribalism and factionalism have filled a power vacuum since Qaddafi’s ouster, and the country has been split between areas controlled by the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord, backed by the UN, and the Libyan National Army, a militia headed by warlord Khalifa Haftar.

Making matters worse, external backers with an interest in Libya have flooded the country with weapons, making it an online hub for the illegal arms trade – and an arid wonderland for terrorist groups.

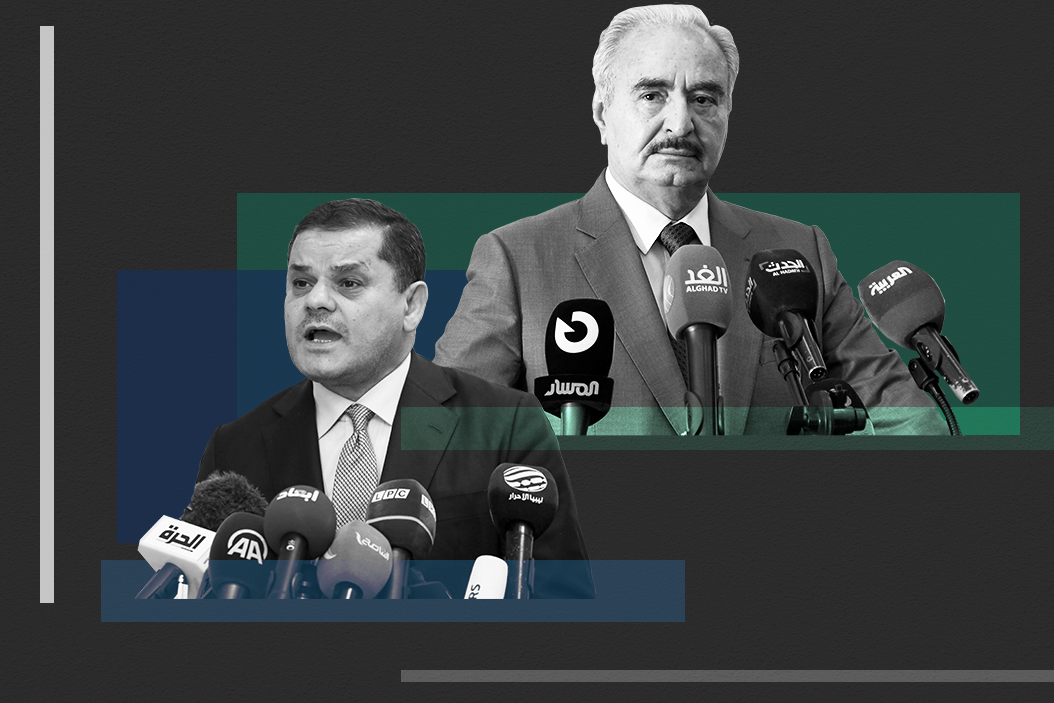

Race to the bottom. Currently, there are three main contenders who could sort of, maybe become president if the vote goes ahead – and if they aren’t banned by the fickle electoral commission. First, there’s interim PM Abdelhamid Dabeiba, a former businessman who heads the GNA. Dabeiba recently lost a vote of confidence in the House of Representatives in the country’s east, and is accused of using state funds to bankroll his candidacy.

Also in the running is Haftar, who heads the militia that led an armed offensive on the capital Tripoli in 2019 after using force to take over the country’s southern oil fields. Members of the renegade LNA have been accused of war crimes.

And finally, there’s Saif Qaddafi, son of the late strongman who played dead for almost a decade. On top of being a verified weirdo who says things like this, “I’ve been away from the Libyan people for 10 years… You need to come back slowly, slowly. Like a striptease,” Saif is also wanted by the International Criminal Court for his role in quashing dissent during the 2011 uprising.

But it’s not just the 3 million Libyans that have registered to vote who are eagerly watching unfolding events. A handful of external players is also keenly keeping track.

The divided view from Europe. Libya, which has the biggest oil reserves in Africa, is awash with liquid gold. That has caused a rift within the EU between Italy – the former colonial power that wants to ensure ongoing access to oil reserves – and France, which has a different set of oil – and broader strategic – interests there.

In addition, the entire EU is concerned with curbing migration flows from Libya to Europe, which have soared in recent years. But France and Italy have different priorities and competing visions of how to secure their interests on that issue, as well.

Paris is banking on the tough-minded Haftar to stabilize Libya and clamp down on extremist elements in society that could be exported to Europe. Italy, meanwhile, has inked a morally dubious immigration agreement with the Libyan government that puts the onus on Tripoli to return would-be asylum-seekers in exchange for cash and training.

The diehard backers. But most of the shots over the past decade have been called by Russia and Turkey, whose respective preoccupations with the country are both economic and ideological.

Russia, which has deployed at least 1,000 mercenaries to bolster Haftar’s forces, has been drilling for oil in the country. Importantly, Moscow also sees Libya as a fertile ground to expand its influence in North Africa while a distracted Washington is focused elsewhere. Turkey, for its part, needs Libya on board to expand its claim over swaths of the energy-rich eastern Mediterranean. (Ankara has signed a contentious maritime border deal with the GNA that gives it access to lucrative gas reserves, infuriating Greece and Cyprus, which have competing claims.)

Moreover, Egypt and a number of Gulf states vehemently oppose the GNA, which includes a faction aligned with the rival Muslim Brotherhood.

Damned if you do and damned if you don’t. Those calling for next week’s vote to be canned say that mistrust is too high, and that whatever the outcome, it will create a new crisis of legitimacy. Others say that the current ceasefire was only meant to be temporary, paving the way for elections now – and that all hell will break loose if the polls are cancelled.

Democracy never comes easily, especially to a country where so many outsiders have big stakes in how it develops.

More For You

When the US shift from defending the postwar rules-based order to challenging it, what kind of global system emerges? CFR President Michael Froman joins Ian Bremmer on the GZERO World Podcast to discuss the global order under Trump's second term.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

- YouTube

At the 62nd Munich Security Conference, GZERO’s Tony Maciulis spoke with Benedikt Franke, Vice Chairman and CEO of the Munich Security Conference, to discuss whether the post-1945 global order is under strain or already unraveling.

- YouTube

At the Munich Security Conference, the mood is clear: Europe no longer assumes the United States will lead. In this Quick Take, Ian Bremmer reports from Munich, where this year’s theme, “Under Destruction,” reflects growing anxiety that the US itself is destabilizing the transatlantic alliance it once anchored.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.