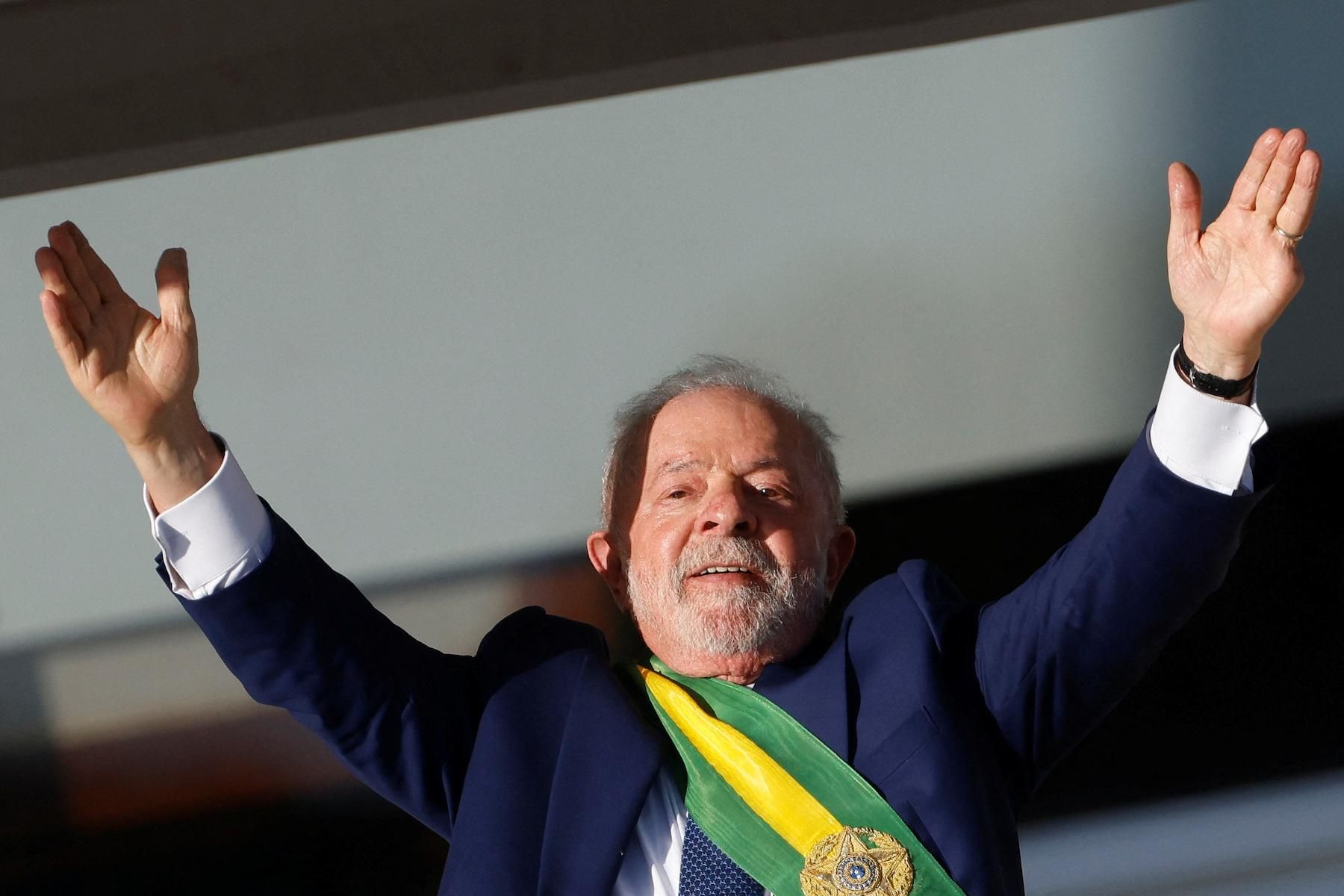

Earlier this week, Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva completed his return from the wilderness.

After 12 rocky years out of power – which included the impeachment of his hand-picked successor, jail time for a corruption conviction that was later overturned, and a narrow election win over his nemesis Jair Bolsonaro – the left-wing former union leader was inaugurated for the third time as Brazil’s president.

The last time Lula lived at the Dawn Palace in Brasilia, from 2003-2010, he oversaw a historic transformation of the country, lifting tens of millions of people out of poverty and putting Brazil on the map as an emerging leader of the new Global South. Small wonder that he left office with an approval rating of 80%. US President Barack Obama once called him “the most popular politician on earth.”

Now, at the start of his third presidential term, Lula says he wants to do many of the same things that characterized his first two: lift millions more into the middle class by increasing social spending, raising wages, reducing hunger, and investing in infrastructure.

The timing of his message is spot on. In the wake of the pandemic, local researchers found that more than 30% of Brazilian households experience moderate or severe hunger – three times higher than a decade ago. The World Bank says a fifth of Brazilians are still “chronically poor.”

But Brazil, and the world outside it, have changed dramatically since the early 2000s in ways that could complicate Lula’s plans fast.

“Lula wants to write the last chapter of his own biography,” says Eurasia Group Brazil expert Silvio Cascione. “He wants to go down in history as Brazil's greatest president ever, but he won't have another chance like what he had in the past.”

For one thing, there’s much less money to throw around. In the 2000s, Lula was blessed with a massive commodity boom, as a roaring Chinese economy gobbled up Brazil’s main exports of soybeans, iron ore, and oil. Historically low interest rates in the US, meanwhile, meant that investors were pouring money into fast-growing markets like Brazil. With annual growth figures averaging around 6%, low levels of inflation, and the government awash in cash, o Brasil ‘tava bombando, as they used to say – “Brazil was booming.”

Today, things are bleaker. Brazil’s economy – battered first by mismanagement under Lula’s successors and then by the pandemic – is growing at barely 2% a year. And while commodity prices are high, the IMF warns that as much as a third of the world may slide into recession this year. No one, meanwhile, is quite sure what will come of Xi Jinping’s grand reopening of the Chinese economy, and high interest rates in the US and Europe are choking off investment in Brazil while making its debt burden loom larger.

The politics are no cakewalk either. In both 2002 and 2006, Lula won the presidency by margins of more than 12 points, while his Workers’ Party had a firm grip on Congress. In last year’s election, by contrast, he scraped through with just 51% of the vote and saw his party lose out in Congress to a coalition that backs Bolsonaro.

“Lula’s mandate is much weaker this time around,” says Brian Winter, a long-time Brazil expert who is editor-in-chief of America’s Quarterly. “It's a much more conservative and vastly more polarized country than it was back in 2003 when Lula first took office.”

So times have changed – has Lula? On the one hand, in order to reach out to a broader swathe of the public, he has named a more politically diverse cabinet than ever before, says Cascione.

His vice president, for example, is one-time rival Geraldo Alckmin, a center-right former governor of São Paulo. “For perspective, this would be roughly akin to Obama coming back and appointing Romney as vice president,” says Winter.

He has also become greener with time. Lula has made protecting the Amazon a far more important part of his platform today than it ever was in the 2000s, when his main concern was reducing poverty. With much of the world keenly focused on climate change, Lula is playing one of Brazil’s best cards at the international table.

But at the same time, experts say that since coming out of prison, he is much more insulated and mistrustful than in the past. “This is probably the most important difference between Lula now and 20 years ago,” says Cascione. “Even if his cabinet is more diverse, he’s relying on a smaller group of people to actually make decisions. And that may lead to more inconsistent policies or make him more prone to error.”

An early signpost: the numbers. To better understand how Lula will govern, and what the response will be, all eyes are on how Lula stakes out his spending plans in the next few months. Although the constitution limits what he can spend, Lula has already convinced Congress to allow him to propose new spending rules of his own this year.

In crafting those, Lula and his Finance Minister Fernando Haddad must tread carefully. He has promised a lot to the Brazilian people, but if financial markets get spooked by his spending plans, the currency could falter, driving up inflation and pushing the country into a fresh recession that would anger voters and embolden his opponents in a hurry.

And that is one of the biggest challenges of all, says Cascione.

“The new middle class that emerged during Lula’s first term is now better informed and much more difficult to satisfy,” explains Cascione, “so not only will the opposition to Lula be stronger, his honeymoon period could be shorter too.”