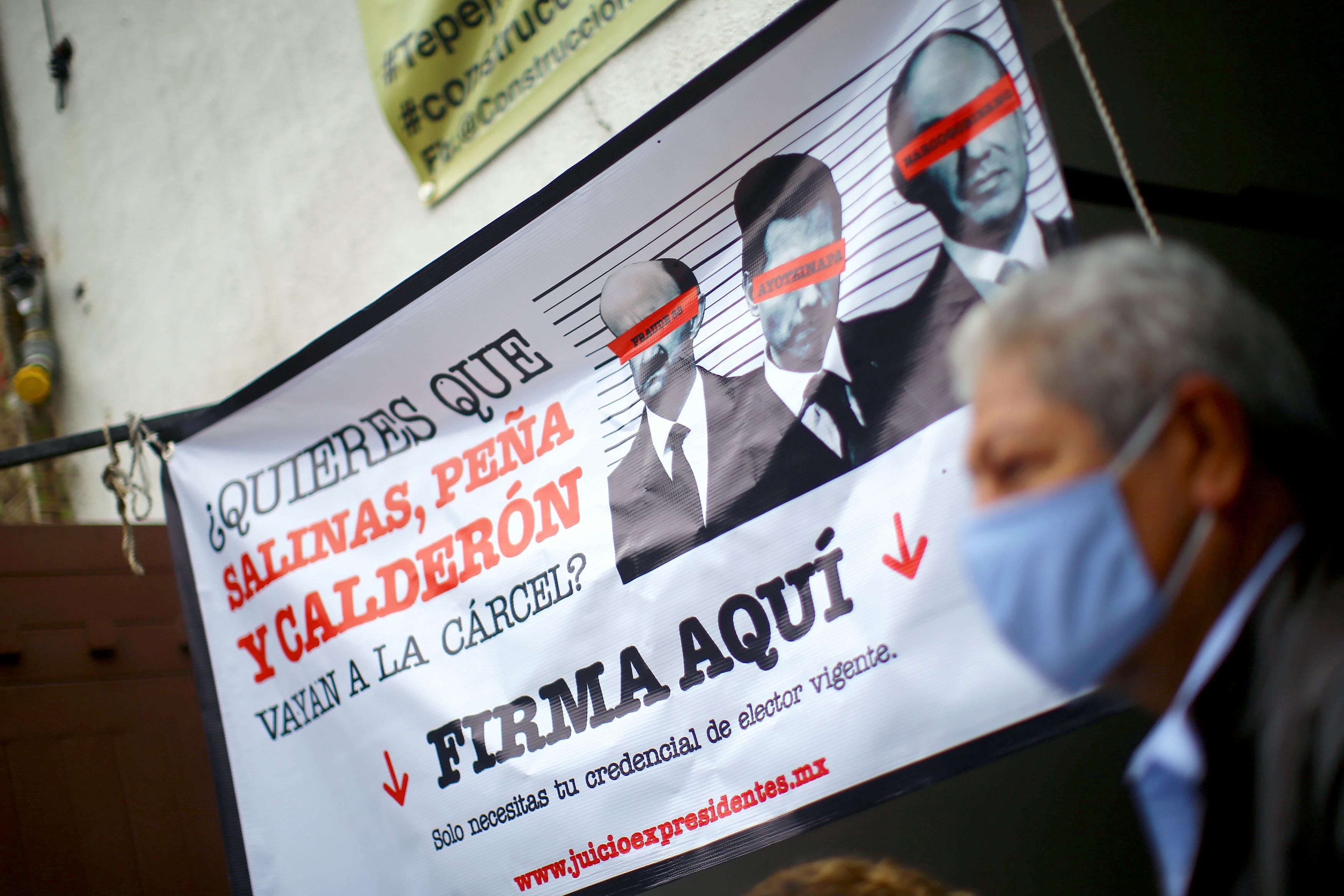

If your country had suffered decades of crippling corruption, wouldn't you want to prosecute those responsible? Of course you would. On Sunday, almost 98 percent of Mexicans who voted in a national referendum on this subject said, in so many words: "Yes, please prosecute the last five presidents for corruption!"

The catch is that turnout was a dismal 7 percent, meaning the plebiscite fell way short of the 40 percent turnout threshold required for its result to be binding.

The consultation was backed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as AMLO, a leftwing populist elected in 2018 in part on his pledge to root out graft and wrestle the power of government back to the common people. Since then he has held a number of non-binding referenda on his policies, and floated a recall vote on his own presidency later this year.

But nearly halfway into his single six-year term, the graft referendum blunder raises some questions about the viability of AMLO's political style, and the future of his ruling MORENA party after he's out of office.

Opponents of the referendum say it was pointless. To be sure, putting former presidents on trial for graft would be a huge deal for Mexico, currently ranked 124th out of 179 nations on perception of corruption by Transparency International. Instead, the question is whether the vote was even necessary in the first place.

There was nothing stopping the government from investigating former presidents — or anyone else — before this. And critics note that AMLO hasn't made much progress against graft anyway. It doesn't help that his sister and brother-in-law have been accused of taking bribes, and that AMLO himself has demanded the US stop funding Mexican anti-corruption NGOs which he says are against him.

Moreover, some of the more fevered theories claim that the whole thing was really a ploy to give a pass to influential former leaders whom AMLO would rather not tangle with after all.

For his supporters, the point of the referendum was to give AMLO a clear mandate to go after former presidents — including the most recent one, Enrique Peña Nieto. But again, almost no one showed up. Even AMLO himself didn't vote, saying, in his typical messianic style, that he favors forgiveness over punishment.

Also, putting everything to a vote is part of AMLO's carefully crafted image of a "man of the people" who wants Mexicans to decide directly on issues of national importance instead of through their elected representatives. Members of his base, whether or not they actually turn up, appreciate being consulted because they've long felt neglected by traditional politicians.

The fact that this plebiscite failed so spectacularly, though, shows us that perhaps some of AMLO's magic touch is wearing thin. Don't forget it was just two months ago that MORENA lost its two-thirds majority in parliament in the midterm elections. All of this jeopardizes AMLO's plans to carry out what he calls Mexico's "Fourth Transformation" because he'll need to get his successor elected in 2024.

Still, AMLO himself remains immensely popular. Although his approval ratings dipped a bit over his handling of COVID and the economy, they have stayed above 60 percent throughout the pandemic. Despite record levels of COVID, crime, economic crisis, and drug cartel-related violence, Mexicans — particularly older and rural ones — still adore AMLO because he's a plainspoken, frugal political outsider who fights for them.

That popularity goes a long way — but if the man himself can't get people to turn up for a referendum on a key issue like this, is there something deeper brewing? AMLO still has three years to sort it out, but the second half of his term is looking a lot more challenging than the first.