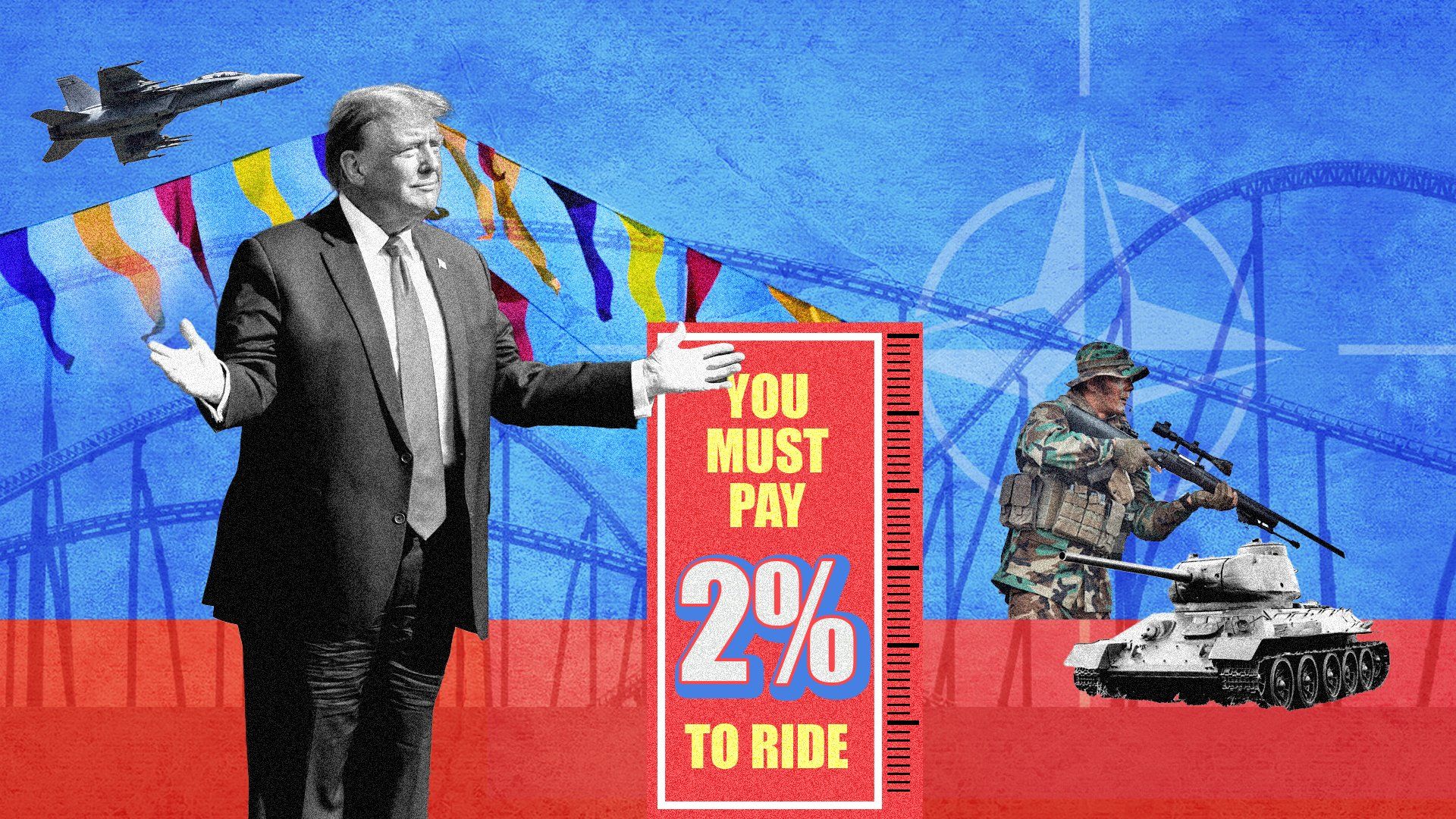

Former president and likely Republican nominee Donald Trump caused a ruckus across the pond over the weekend when he said that he would encourage Russia to attack any NATO member falling short on their defense spending goals (2% of GDP or more). Predictably, this got America’s European allies, most of whom were already pretty agitated about the prospect of a second Trump presidency, decidedly panicky.

It's easy to see why. During his first term in the White House, Trump repeatedly threatened to pull back from longstanding US security commitments to NATO as a lever to force European allies to shoulder more of the financial burden of their defense and to secure favorable trade concessions. His latest remarks are the first, however, explicitly encouraging Russia – a country openly hostile to NATO and currently leading a war of aggression in Ukraine – to attack other NATO members. Despite significant increases in defense spending since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, European allies are still largely dependent on US military capabilities to maintain credible deterrence. If Trump were to act on his threats at a time when war is raging on Europe’s doorstep, Ukraine’s prospects for victory are shrinking, and Russia’s expansionist appetite remains unsated, Europe would find itself in an unenviable position.

At the same time, there is a point beneath Trump’s threats. It is indeed the case that most of the largest NATO economies – including Germany, France, Italy, and Spain – have been underinvesting in their own defense for decades, confident that the “peace dividend” would last forever or else that they could free-ride on the US security guarantee indefinitely...despite continued pleas from US presidents of both parties for them to become more co-equal partners in European security. Yet they have been allowed to get away with this rather unacceptable state of affairs at their own peril, their consistent failure to invest in their own defense weakening NATO and emboldening Vladimir Putin as much as (if not more than) any Trump statement could.

In that sense, Trump’s escalating withdrawal/abandonment threats are important for both Europe and NATO in the long term, insofar as European leaders find them credible enough to finally start taking European security seriously. Asking them hasn’t worked. And the status quo is increasingly untenable to growing numbers of Americans.

Admittedly, the gambit is not without downsides. The threat of withdrawal/abandonment risks turning NATO, which has historically been widely understood as a strategic alliance in America’s own vital security interest, into a largely transactional arrangement. You may think transactional doesn’t sound so bad – they get something, we get something, everyone wins, right? But that’s not how military alliances and deterrence work. The moment it becomes clear that NATO is bound not by trust and shared interests but by quid pro quo, the security guarantee is rendered less credible in the eyes of adversaries (who know the US will not go to war to defend another country solely for money) and therefore less valuable for partners.

Most importantly, this assumes that Trump is playing hardball and just wants to leverage the US security guarantee to get the Europeans to pull more of their weight and to secure gains in other areas such as trade, much like he did in his first term. However, there are those who have worked with him, such as former national security adviser John Bolton, who believe that Trump doesn’t actually care whether NATO members increase their burden-sharing and is just looking for a pretext to abandon an alliance he has always seen as an inherently bad deal for America. According to Bolton, it's not a bluff, it’s not a negotiating tactic, it’s not even a shakedown: it’s his deeply-held policy stance. Big if true, as they say.

This would be the ultimate nightmare scenario for the Europeans, who have neither the leadership, the cash, nor the trust to fill the gaping hole left by the (de facto or de jure) withdrawal of the US security guarantee. Rather than galvanize the continent, political and military fragmentation would ensue. Some countries would try to “buy” bilateral security agreements from the Trump administration, while others would cozy up to Moscow instead. Yet others, such as the Nordic and Baltic states, would band together in regional security groupings.

The damage to European unity and security would be heavy. But so would the damage to America’s credibility and global standing.