October 17, 2024

“This play is a search for answers,” Erika Sheffer wrote about her new play, “Vladimir.” “It is a howl of rage. It is also an extended hand.”

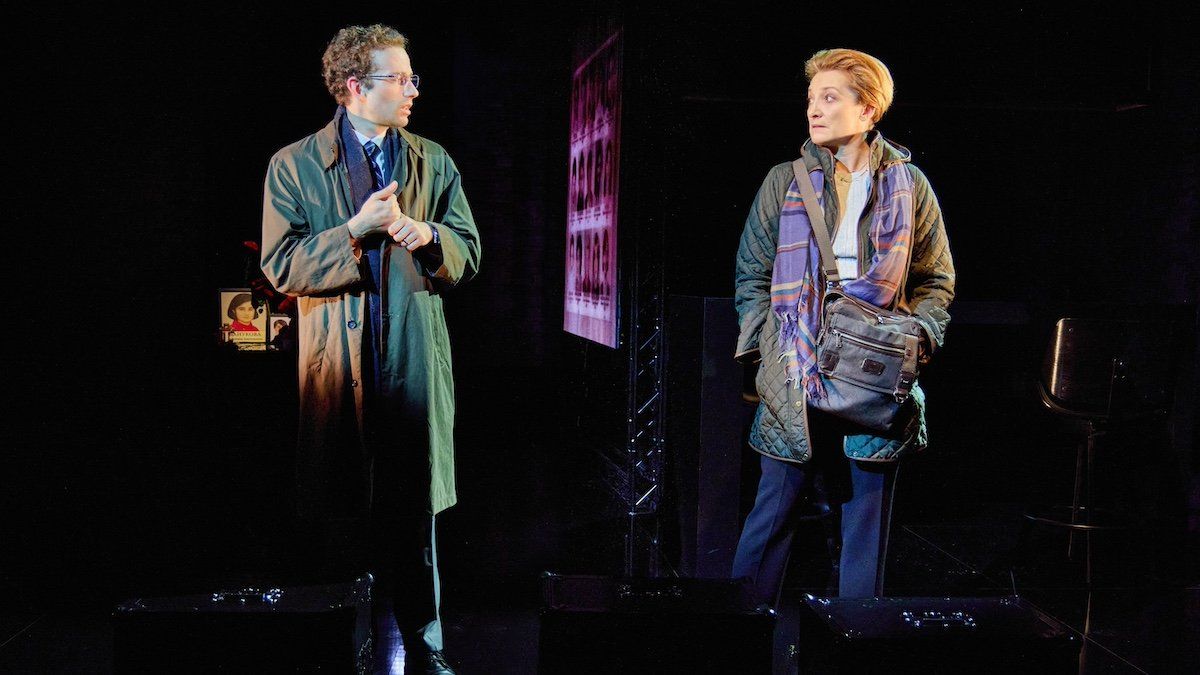

In “Vladimir,” which had its world premiere this week at New York City Center, Sheffer explores the critical moment a “society finds itself on the brink.” In this case, the society is Russia in the early years of Vladimir Putin’s presidency.

A tough-as-nails journalist, Raisa “Raya” Bobrinskaya, the protagonist, is determined to expose government corruption and continue her perilous work covering an ongoing war in Chechnya. Shortly after Putin’s 2004 “reelection,” crackdowns on journalists and dissenting voices ratchet up the danger in her daily life. The people around her — colleagues, sources, and family members — are forced to choose between bravery and survival.

Sheffer tells me she sees parallels in the current state of US politics as the presidential election approaches, including polarization and widespread disinformation, that undermine democracy. We talked about that, and what she learned about human nature in the process of writing the play.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tony Maciulis: This is not your first play dealing with Russian subject matter. “Russian Transport” examined immigrants living in the United States. How has your personal backstory influenced your work?

Erika Sheffer: My parents came here from the Soviet Union in 1975 with my brother, who was quite young. They’re from Western Ukraine, but they grew up in the USSR. They spoke Russian and some Hungarian and went to Russian schools, and so they came as refugees. They couldn’t go back to the USSR for many years and didn’t. And then the rest of my family came in the ’90s after the fall of the Soviet Union. I was always interested in the ways in which their psychology was quite different from mine, having such a different upbringing, and that’s influenced a lot of my writing.

Maciulis: Earlier this year, the play “Patriots,” by Peter Morgan, explored this same moment in Russian history but with a deep focus on Putin himself and his enablers. Yours is about everyday people and their relationships. Why that angle?

Sheffer: I mean, truthfully, I’m not as interested in whether oligarchs will have a little more money or a little less money. I come from a working-class family, I should say. My characters are mostly within the intelligentsia. They’re not working class. But at the same time, their concerns are their family, their loved ones, sort of how do I move through a society that is rapidly changing and getting scarier by the day? And for me, that holds a lot more interest, and the stakes feel smaller, but at the same time much bigger.

Maciulis: Your characters all have their courage tested, and we see relationships deteriorate. But we also see Raya build real trust with her sources — Chovka, a young Chechen rebel, and Yevgeny, a Ukrainian immigrant caught in an explosive tax scandal.

Sheffer: I think it does interest me how a journalist gets a source to work against their own interests in the service of something larger, which I think both those characters do. And that part of Raya’s job is figuring out the ways in which to entice people to do that — because that’s tough. That’s definitely a facet of the career that I was interested in exploring. When I was reading about Anna Politkovskaya and Sergei Magnitsky and all these other journalists and activists and obviously [Alexei] Navalny, what makes you go that far in a country that maybe has never really had a free and fair democracy? Where do that belief and that determination to fight for it despite not having had it in a real meaningful way come from?

Maciulis: And there are others who do not fight, who retreat in the face of this oppression. Raya tells Yevgeny she sees that as apathy. His response was so moving.

Sheffer: He says, “Maybe it’s genuine fear.” And that I understand. My grandparents were Holocaust survivors, but then my grandfather, when they were in the Soviet Union, went to prison for four years for selling jewelry on the black market, which was pretty common. But my grandmother also went to prison for not turning him in. They were both taken away from their kids. She was an Auschwitz survivor, and then she went to the gulag for not turning her husband in. So, I think that fear is real. Raya’s saying it’s apathy, and Yevgeny’s saying, no, we’re afraid, and we have reason to be.

Maciulis: It’s hard to watch this play and not think you are offering a cautionary tale to an American audience. Are you?

Sheffer: Maybe. I do think our history of being able to speak out is important, but you do have these forces eroding democratic norms and eroding people’s ability to vote for the leaders they want to vote for. And I think that is a scary thought. And I also think the lesson about Russia to me is that it happened slowly, slowly, and then all at once. I hope we’re not at the slowly, slowly [phase]. It’s funny, there was a quote by Gary Shteyngart about how he always thought Russia would end up becoming more like America, but America’s actually becoming more like Russia – and he’s from Russia and came here as a child. I think it’s scary, and it definitely reminds me of Russia, but there is an openness of communication here that I think is quite different.

Maciulis: Finally, you wrote in a note to your audience, “Let’s always be a nation striving toward something better.” Do you believe that we collectively are striving toward something better right now?

Sheffer: I don’t know that we’re collectively striving toward something better, but I don’t know that it always takes people collectively striving toward something better. I think sometimes it takes a really dedicated number of people striving toward something better to move the culture. And I do think, as a country, we are still capable of that.

More For You

- YouTube

GZERO World heads to the World Economic Forum in Davos, where Ian Bremmer lookst at how President Trump’s second term is rattling Europe, reshaping both transatlantic relations and the global economy, with Finland’s President Alexander Stubb and the IMF’s Kristalina Georgieva.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

- YouTube

How widely is AI actually being used, and where is adoption falling behind? Speaking at the 2026 World Economic Forum in Davos, Brad Smith, Vice Chair and President of Microsoft, outlined how AI adoption can be measured through what he calls a “diffusion index.”

U.S. President Donald Trump holds a bilateral meeting with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland, January 21, 2026.

REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

After saying numerous times that he would only accept a deal that puts Greenland under US control, President Donald Trump emerged from his meeting with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte singing a different tune.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.