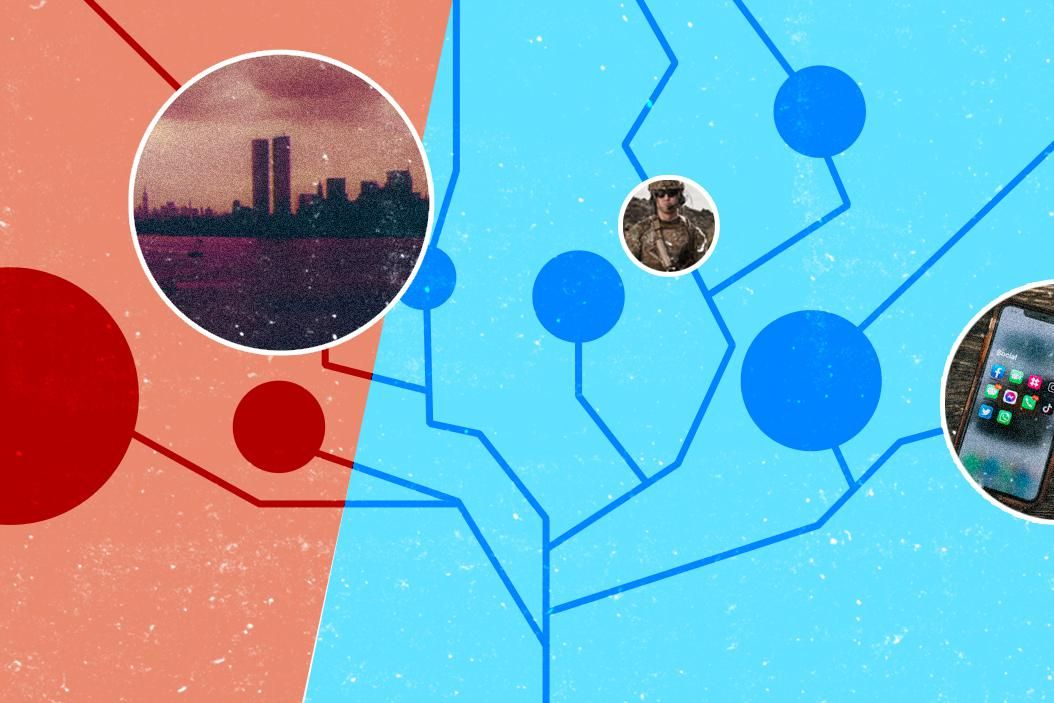

As pivotal as they were, there was certainly nothing inevitable about the September 11th attacks — or their aftermath. Here we imagine five separate scenarios for how things might have gone differently.

The social media 9/11

As the wounded Twin Towers belch smoke and flames into the sky, social media lights up with videos from people within the buildings, documenting their desperate final moments as they go "live." Within hours of the towers' fall, a Staten Island man uploads a shaky hand-held clip of the North Tower's collapse. The clip purports to show that explosives were used to weaken key structural points of the building, hastening its fall. Algorithms instantly spirit this lie to millions of other users, while thousands of anonymous trolls, in the US and abroad, begin fanning the flames of a conspiracy theory about who was actually responsible. By the time President Bush shouts through a bullhorn at Ground Zero three days later that "the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!" it's not clear who "us" is. An anguished America is deeply divided about what happened, confused about what the government intends to do in response, and mistrustful of the mainstream media who seem to be towing the government line.

Of course, conspiracy theories and deep political divisions emerged in the years after 9/11 even without social media — but they bubbled up slowly and eccentrically, rather than with the furious immediacy made possible by smartphones and even smarter algorithms. If a similar attack were to occur today, would there be any real unity at all in the aftermath?

Drafting off of 9/11

On September 18th, 2001, just a week after the attacks, President Bush, riding a wave of patriotic unity and fervor, signs a new law reinstating the military draft for the first time in twenty-eight years. As the United States prepares to launch a retaliatory strike in Afghanistan against the Taliban and its al-Qaeda houseguests, tens of thousands of American men between 18 and 25 receive draft cards — they must either report for military service, or do a year of civic service. The stakes of the Global War on Terror, then in its infancy, are immediately clear for everyone, even across America's deepening geographic, political, and socioeconomic divides. There is broad support for the Afghanistan mission, but as the Bush administration begins laying the groundwork for an invasion of Iraq, there is more skepticism from the public. Because of that, the mainstream media applies more scrutiny to the administration's claims about WMDs, and the linkages between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden.

Does the Iraq invasion end up happening? And, years later, is America a less polarized place because of the draft?

The Taliban hand over bin Laden, US doesn't invade Afghanistan.

Less than 24 hours after al-Qaeda attacks America, the Taliban don't even wait for the US to come knocking. They immediately offer to hand over Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda's leaders to avoid an American invasion and a war they know will end with yet another foreign power occupying Afghanistan for years. Once in US custody, bin Laden and his lieutenants are sent to the US military base in Gauntánamo, Cuba, where they are interrogated for months before a secret trial. Meanwhile, the Taliban hold onto power, but only because the leader of their main enemy, the Northern Alliance, was killed by al-Qaeda two days before 9/11.

Does not getting bogged down in Afghanistan — and later Iraq — make it easier for the US to actually win the Global War on Terror? Do the Taliban stay in power in Afghanistan? And what happens to al-Qaeda once its leaders vanish?

The US does attack Afghanistan, but with a clear plan and exit strategy.

After the dust settles on the ruins of Lower Manhattan and the Pentagon, President Bush tells the nation he'll follow his dad's recommendation to respond to 9/11 like the US did to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait a decade ago. America will seek a UN resolution authorizing a US-led coalition to attack Afghanistan with the sole purpose of capturing al-Qaeda's leaders and putting them on trial in the United States. America wants to do things by the book, but is not keen on a lengthy legal process at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, which cannot hand down the death penalty. US forces get ready to strike Afghanistan with a coalition of almost 100 countries, many of them Arab states angry at the Taliban for helping al-Qaeda commit such a massacre.

How would a truly multilateral, Gulf War-style plan have changed things in the Global War on Terror? And would backing from Muslim-majority countries have made a difference? What would have happened to Afghanistan after a US-led military campaign that ends without America as an occupying power?

It never happened.

On the morning of September 7, 2001, President Bush convenes a press conference with newly appointed FBI chief Robert Mueller and CIA director George Tenet. They announce that a massive terrorist plot against the United States has been uncovered and thwarted. So far, more than a dozen nationals of Saudi Arabia and Egypt have been arrested in three different states for planning to hijack airplanes and fly them into several, as yet unknown, targets along the East Coast of the US.

If the whole thing had never happened, what would have come next? Let us know what you think — if you do, be sure to include your name and location as you'd like them to be cited, just in case we decide to publish.