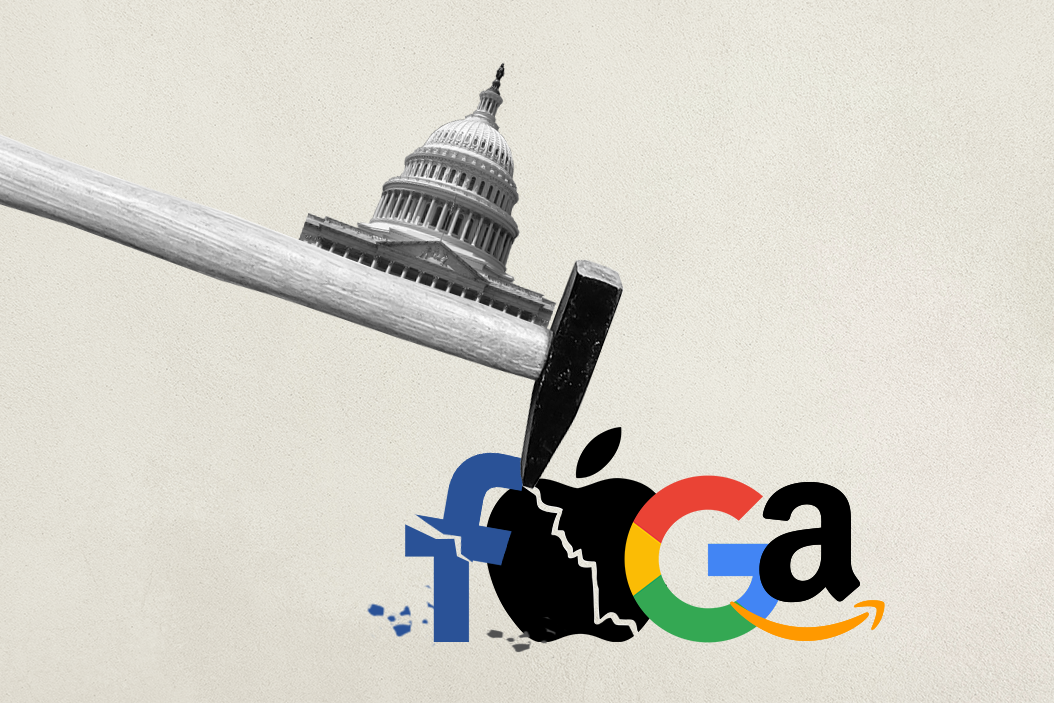

"Don't be evil", they said. Back in 2000, that was the internal motto of a scrappy little tech startup called Google. Twenty years later, and a trillion dollars higher in market cap, the company, along with fellow tech giants Amazon, Apple, and Facebook, is squarely in the crosshairs of US lawmakers who say their business models have gone to the dark side.

The latest challenge — a 450-page report released Tuesday by the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives — says the four biggest US tech giants have abused their market power to undercut rivals and stifle competition, putting their users' economic and political freedoms at risk. The companies themselves say their businesses have created untold numbers of new jobs, markets, and innovations that previously did not exist.

Qualms about big tech firms' market power aren't new. The Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission are already conducting antitrust probes of all four companies, but the report lays out the case in detail. It also makes a series of recommendations for lawmakers on how to update competition laws and strengthen oversight of tech firms. Some of those calls go as far as to explore breaking up the companies.

Could the Beltway really take a tougher line on Silicon Valley? Democrats and Republicans (who rarely see eye to eye on anything these days) generally agree that Big Tech needs to be reined in, although they have often disagreed about why and how. Two Republican members of the House subcommittee that released the new report put out their own dissenting documents on the same day. One faulted the main report for failing to address what Republicans believe is an anti-conservative bias on social media. The other, more substantively, agreed with the main report's call to update antitrust laws, but rejected breaking up firms.

The lack of a durable bipartisan consensus means the November election will be critical. If the Democrats take control of the Senate, they'd be in a more commanding position to advance some of the report's proposals. The main players to watch would likely be senators Elizabeth Warren, who has been outspoken in her calls to break up big tech, and Amy Klobuchar, a major digital privacy and antitrust advocate who would likely lead the Senate antitrust subcommittee.

Still, Silicon valley has immense lobbying power to fight tougher regulations, and it's not clear that a centrist like Chuck Schumer, who would likely take the helm of a Democrat-controlled Senate, would relish a big fight on this issue any time soon.

Meanwhile, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has, like his opponent Donald Trump, called for reform of the so-called "Section 230" protections that shield social media firms from liability for content posted on their sites. But although he's criticized Big Tech's market dominance, he'd have a lot on his plate if he won — tech regulation would probably take a back seat to the pandemic, economy, foreign policy, and climate change.

Is there a US-China angle here? Well it's tech, so of course there is. The US and China are moving into an increasingly zero-sum rivalry over technologies like 5G and artificial intelligence, in which the tech giants are major players. If this turns into a 21st-century "tech Cold War" in which firms on either side of the Pacific are the main combatants, US companies will be facing off against Chinese rivals (like Huawei) that have the firm support of the Chinese government, and face few antitrust constraints of their own.

Under those circumstances, will US lawmakers — who seem to agree across party lines on the need to confront China — think twice about putting fresh constraints on America's heavyweight fighters? Or would they reason that regulating Big Tech better would ease some of the social polarization that afflicts the US, and create an even more powerful and innovative economy in the future?