The Democrats run Washington – so what are they scared of?

The Democrats currently control the House, Senate, and White House for the first time in more than ten years. That enviable position, which came to them after unexpectedly winning two Senate runoffs in January, has allowed them to pass President Joe Biden's $1.9 trillion recovery and stimulus plan and to tee up another package of up to $4 trillion of investments in green energy and other priorities.

Democrats with unified control of government, a popular new president, and passing ambitious agenda items aimed at making a green recovery from a deep recession — sound familiar?

This is almost exactly the situation former president Barack Obama enjoyed in 2009-2010. But the rest of the decade was largely disappointing for Democrats. Though Obama was reelected in 2012, the party lost the House in 2010, the Senate in 2014, as well as 958 state legislative seats over the course of Obama's presidency. Donald Trump's win in 2016 — and Republicans' capture of the House and Senate — capped off this dismal period of Democratic decline.

As in 2010, Democrats today face several converging threats to their ability to hold on to power. Unlike a decade ago, the party can see them coming, but internal disagreements and the persistence of the Senate filibuster may make it hard for Democrats to head off a loss of power, even though they currently control Washington.

So what is it that they are worried about?

To start with, the party in power almost always pays a price in its first midterms. This is as close to an iron law as exists in US politics. The only two presidents to break it did so amid seismic political events: Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 at the height of the Great Depression, and George W. Bush in 2002 after the 9/11 attacks.

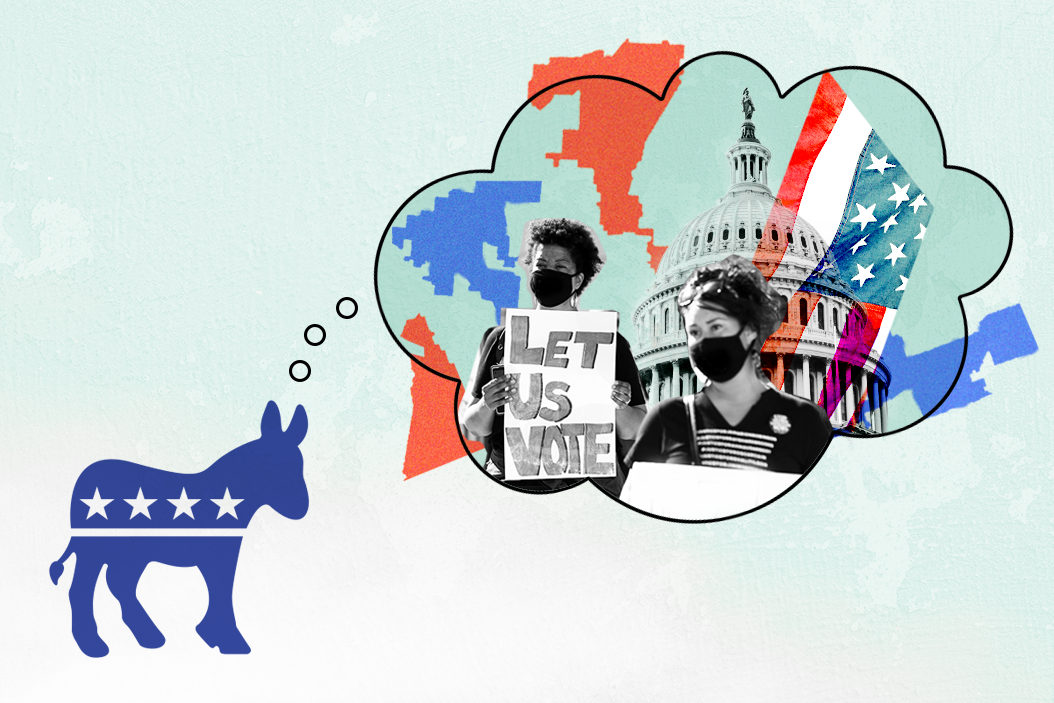

What's more, Republicans at the state level have embraced voter suppression as a political tactic. In more than a dozen states under unified GOP control, legislators are considering measures to restrict access to voting. Most of these measures will disproportionately hurt the access of Democratic constituencies — Black people, young people, and the poor — to the ballot.These efforts are directly connected to Trump's false claims that the 2020 election was stolen from him, and they're popular with the GOP base.

Back in DC, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court is once again reviewing the Voting Rights Act, a landmark piece of legislation that offers broad protections for people's right to vote.. In Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, the court effectively overturned the act's Section 5. A case the court heard in early March could overturn Section 2, which allows legal challenges to voting rules on the basis of discriminatory impact. Challenges under Section 2 were crucial to Democrats' legal efforts to contest restrictive voting rules in the runup to the 2020 election.

Democrats are also expected to lose out in the US's once-a-decade redistricting process, which determines the map of congressional districts. After huge Republican gains in state legislatures in the 2010 cycle, the GOP was able to draw favorable districts in key states, ensuring an advantage in Congress even in states where the partisan split was relatively even. Ahead of the 2020 cycle, Democrats identified this as a problem, but efforts to flip state legislative chambers last year mostly failed. As a result, Republicans will once again draw the borders for many more congressional districts that will take effect in 2022: 181, versus only 53 for the Democrats.

Finally, Democrats have seen their demographic hopes thrown into question by the 2020 election. For years, Democrats had seen the US's changing demographics as a key advantage, reasoning they stood to benefit as the country became less white. But Trump, despite his frequent use of racially incendiary rhetoric, actually improved his position in 2020 with Black men (+6 percent), Hispanics (+4 percent), and Asian Americans (+7 percent) versus his 2016 performance, likely a result of a strong economy that ran closer to full employment than the US has in decades (until the coronavirus hit). That means that Democrats can't necessarily count on demographic change to inexorably shift big states like Texas into their camp.

The Democrats aren't asleep at the wheel, of course. House Democrats have passed two pieces of legislation that could address some of these problems: HR.1, which sets minimum voting standards for states, and HR.4, which strengthens the Voting Rights Act. But Republicans are universally opposed to both, so neither can pass the Senate's 60-vote filibuster threshold for most legislation.

That has strengthened calls for Democrats to reform or abolish the filibuster. Several Democratic senators have expressed a willingness to do so in recent weeks, but a critical group of moderate Democrats continues to defend the 60-vote requirement. One potential compromise could be a carveout from the filibuster for civil and voting rights legislation, but even that solution doesn't yet have the universal support it would need among Senate Democrats. Moderates — especially those from states that voted for Trump — face very different political incentives than their colleagues from safe Democratic districts, with their political futures dependent on their ability to distinguish themselves from the unpopular brand of the national Democratic Party. That gives them little incentive to support voting reforms that the GOP is already attacking as a nationalization of voting that opens the door to fraud.

In the meantime, Democrats' sense of impending doom is pushing them to do as much as they can, as quickly as they can, trying to make as much policy as possible before they lose power. Democrats know that unless they can resolve the contradictions between the political incentives of moderates and progressives, they may be doomed to see history repeat itself.

Jeffrey Wright is Analyst, United States at Eurasia Group.

- No, Joe Biden, America is not back. It will take time. - GZERO Media ›

- US Senate races matter... to the world - GZERO Media ›

- US politics will become more divided under Biden - GZERO Media ›

- Elise Stefanik’s rise in the Republican Party - GZERO Media ›

- Elise Stefanik’s rise in the Republican Party - GZERO Media ›

- Affordable Care Act upheld by Supreme Court, and Republicans move on - GZERO Media ›

- Why election reform laws are deadlocked on Capitol Hill - GZERO Media ›

- Why election reform laws are deadlocked on Capitol Hill - GZERO Media ›

- Democrats need to be united to pass $3.5 trillion budget plan - GZERO Media ›

- Democrats need to be united to pass $3.5 trillion budget plan - GZERO Media ›

- How the Democrats plan to tax the rich; Newsom wins CA recall - GZERO Media ›

- Should the US cancel student loan debt? - GZERO Media ›

- Voting reform bill stalls in Congress, frustrating Democrats - GZERO Media ›

- The implications of Senator Feinstein's passing - GZERO Media ›