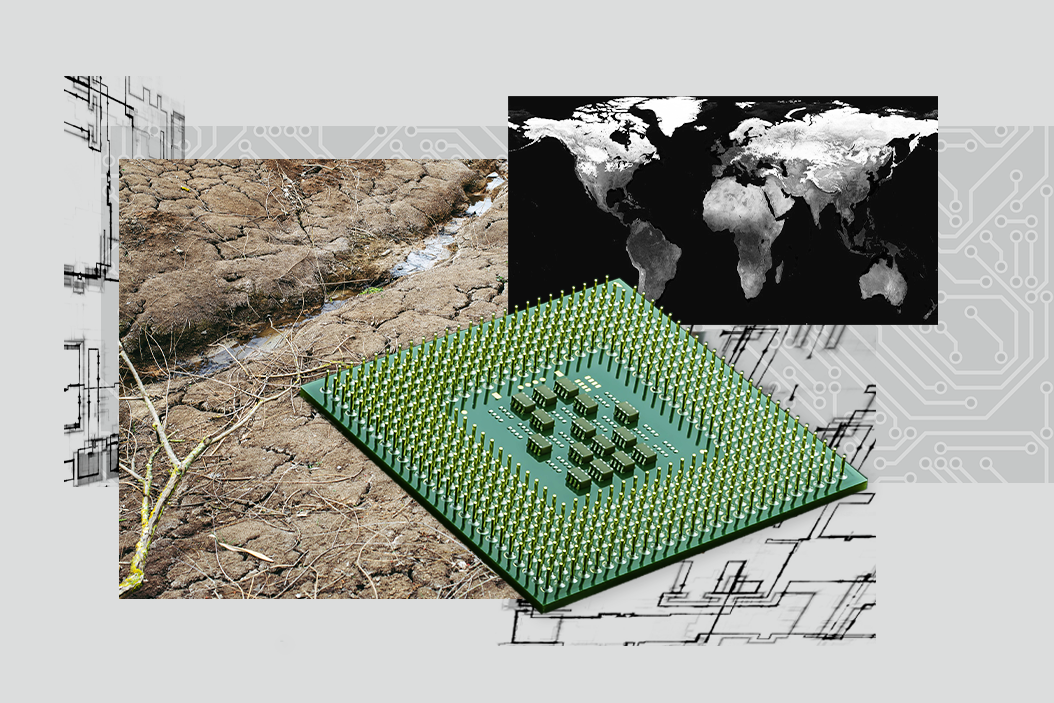

Why may a drought in Taiwan perhaps screw up your next computer purchase?

For one thing, the island is one of the world's top producers of semiconductors, which bind the electrical circuits in the tech we use in our daily lives. Cell phones, laptops, modern cars, and even airplanes all rely on these tiny computer chips. For another, Taiwan is now suffering its worst climate change-related dry spell in almost 70 years. This is a problem because Taiwanese chip factories consume huge amounts of water.

The wider issue, though, is a pandemic-fueled worldwide chip shortage that began way before it stopped raining in Taiwan, has wreaked havoc on entire sectors like the US auto industry, and is shaking up the increasingly contentious geopolitics of global supply chains.

COVID upended supply/demand. In the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, auto makers around the world assumed people quarantining at home would probably buy fewer cars, so they ordered fewer semiconductors. Meanwhile, other companies were scrambling for all the chips they could get their hands on for personal computers and video game graphics cards, which have been flying off the shelves during COVID lockdowns.

A year later, car manufacturers have been forced to halt assembly lines because they can't get hold of chips for anti-lock brakes, air bags, navigation, and in-car entertainment systems. Sales of the products that locked up the inventory of semiconductors are booming.

So, why don't we just make more? Because it's not that easy. Semiconductors are highly specialized products that rely on global supply chains that have been severely disrupted by COVID. If one part is missing or late, you can't make the chips (this is precisely what happened with broken supply chain links after the 2011 Fukushima disaster.)

The US is the top global producer of semiconductors but consumes most of its own chips, while China — by far the biggest consumer — makes a lot itself and gobbles up most of the supply from South Korea, Taiwan, and India. Very little is left over for other customers from the rest of the world.

What are the US and Europe doing about it? Americans and Europeans were already thinking about ways to reduce their reliance on cheap Asian chip suppliers before the recent shortages hit — they're both teeing up tens of billions of dollars in subsidies to entice the world's leading suppliers to build advanced facilities within their borders, like Taiwan's TSMC in Arizona.

The current squeeze, which has cost Ford and General Motors a combined $4.5 billion in losses, has increased the political urgency for President Biden and Congress. But ramping up domestic production of semiconductors in the US and Europe will be immensely expensive, and will take too long to address the current shortfall.

Meanwhile, the Chinese are burning through cash to get a bigger slice of the global semiconductor pie. Chips are so essential to feed China's tech beast that last year Chinese firms spent over $35 billion in ramping up production, four times more than in 2019.

Beijing cannot afford to rely on foreign suppliers in its race with the US to dominate artificial intelligence or quantum computing. They don't want to go through hoops like Huawei, which was forced to stockpile chips following Trump trade war-related US export restrictions on Taiwanese semiconductor.

Taiwan is the big kahuna. One of the (many) reasons President Xi Jinping is pushing harder than ever to annex Taiwan is the self-governing island's outsized chip manufacturing capacity. TSMC alone makes more than half of the chips outsourced by all foreign companies, which means your iPhone runs on Taiwanese-made semiconductors. If China were to someday reunify Taiwan with the mainland, it would become such a chip juggernaut that it could bend individual countries to its will by controlling supply — as the Chinese often do with their rare earth metals.

The US, for its part, has its own clear interest in propping up Taiwan as a global chip-making power. Taiwanese-made semiconductors are cheaper than those produced on US soil, and the more are sold to the US and its allies, the less China gets.

But if climate change makes not only droughts but also earthquakes and typhoons more frequent in Taiwan, global chip shortages will become a recurring problem — and geopolitical power struggle — for the entire world.

- Biden's vaccine diplomacy and US global leadership; US-China bill gets bipartisan support - GZERO Media ›

- Report: China's cyber security a decade behind the US, despite hype - GZERO Media ›

- Will China's tech sector be held back? - GZERO Media ›

- Rishi Sunak vs UK economic crisis - GZERO Media ›

- Taiwan's secret shield against Chinese invasion: its semiconductor industry - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: America at risk: assessing Russia, China, and domestic threats - GZERO Media ›

- Xi Jinping's Solution to his "Taiwan Problem" - GZERO Media ›

- Taiwan’s outsize importance in manufacturing semiconductor chips - GZERO Media ›

- How democracies nurture the growth of artificial intelligence - GZERO Media ›

- Ian Bremmer on the forces behind the geopolitical recession - GZERO Media ›

- The rise of global impunity in a G-Zero world - GZERO Media ›

- US aims to maintain military advantage over China by controlling tech - GZERO Media ›

- Climate change is "wreaking havoc" on supply chains - GZERO Media ›

More For You

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, with President of the European Council António Luís Santos da Costa, and President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, at Hyderabad House, in New Delhi, India, on Jan. 27, 2026.

On Tuesday, the world’s largest single market and the world’s most populous country cinched a deal that will slash or reduce tariffs on the vast majority of the products they trade.

Most Popular

Five forces that shaped 2025

What’s Good Wednesdays™, January 28, 2026

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney has repeatedly tussled with US President Donald Trump, whereas Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has tried to placate him. The discrepancy raises questions about the best way to approach the US leader.

10,000: The number of Hamas officers that the militant group reportedly wants to incorporate into the US-backed Palestinian administration for Gaza, in the form of a police force.

Walmart is investing $350 billion in US manufacturing. Over two-thirds of the products Walmart buys are made, grown, or assembled in America, like healthy dried fruit from The Ugly Co. The sustainable fruit is sourced directly from fourth-generation farmers in Farmersville, California, and delivered to your neighborhood Walmart shelves. Discover how Walmart's investment is supporting communities and fueling jobs across the nation.