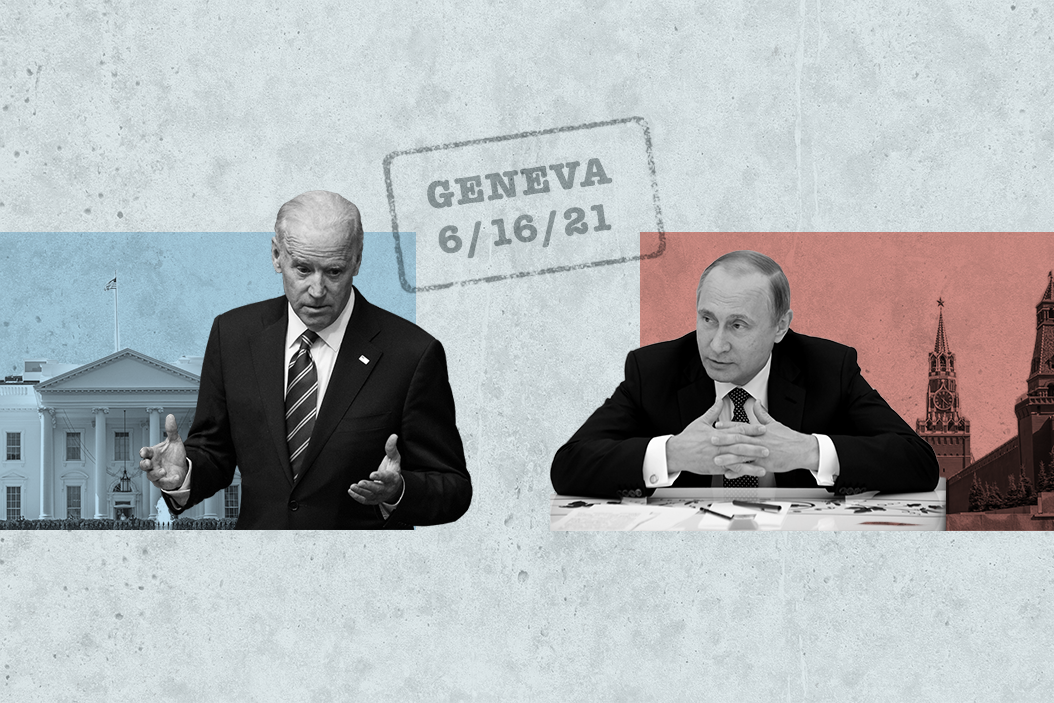

Joe Biden is meeting with Vladimir Putin on Wednesday, and the first thing to say about that is: temper your expectations.

US-Russia relations are at their worst point since the end of the Cold War and perhaps even before that. The US has imposed dozens of economic sanctions on Russia over election meddling, human rights abuses, and the illegal annexation of Crimea.

On a personal level, it's worse: Ronald Reagan may not have fully trusted the Soviets, but he never said — as Biden has done of Putin — that Mikhail Gorbachev was a murderer with no soul. At least not publicly.

The relationship is strained over many things, but they boil down to one big thing: the US still sees itself as a global superpower and Russia is unwilling to accept second-fiddle status.

So while the US considers Moscow a menace — meddling in elections, invading countries in Europe, backing dictators around the world — Moscow sees the US as an arrogant colossus, encroaching on Russia's sphere of influence, waging endless destabilizing wars in the Middle East, and lecturing the world about democracy from a badly broken pedestal of its own.

In other words, there are deep structural problems in the US-Russian relationship, and there's little the two presidents can do to change that with one sit-down in Geneva.

Still, Biden has said he wants to lay the groundwork for a "stable and predictable" relationship. So to get a sense of what we might expect, I asked Alex Brideau, the lead Russia expert at Eurasia Group, our parent company. Here's a lightly edited rundown of what he said.

What are the key points of disagreement?

Plenty, and there are no easy fixes. Biden will almost certainly bring up the recent ransomware attacks on the Colonial Pipeline and the meat processor JBS. The US says they were carried out by criminal groups in Russia and blames the Kremlin for not doing enough to stop them. Biden also wants to send a strong message to Putin about Russian meddling in US elections and will likely raise the treatment of imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Putin will of course disregard this as US interference in Russia's internal affairs.

Putin will have demands of his own, in particular about the seven-year-long conflict between Ukrainian government forces and Russia-backed separatists in Eastern Ukraine, which has already claimed more than 14,000 lives. Putin, who denies Russian involvement, wants Biden to lean on the Ukrainian government to negotiate directly with the separatists to jumpstart a political reconciliation with them. Biden, however, supports the Ukrainian position that Russia must negotiate with Kyiv and make security concessions before a political settlement.

And where exactly can Biden and Putin cooperate?

There aren't many areas, but there are some important ones. Both leaders want progress on nuclear arms control. At the beginning of Biden's term they renewed the New START treaty for five years, rescuing the last major US-Russia strategic arms control pact from oblivion. They also see eye-to-eye on reviving the Iran nuclear deal, where Russia-US talks seem to be going very well. Lastly, they may discuss use of the Arctic, where despite some border disputes, they have an interest in avoiding escalation, and each wants to limit Chinese influence in the region.

How is the meeting perceived in Washington and Moscow?

Washington on the whole is fairly hawkish toward Russia. And Biden's decision to meet with Putin has faced skepticism from members of Congress who don't see much upside.

Russian officials meanwhile have little expectation that US economic sanctions against Russia — which came in response to US election interference, Ukraine, and the poisoning of Russian dissidents — will be eased any time soon. But there is hope that the summit could bring the temperature down a bit, by engaging on issues of common concern, thereby lowering the likelihood of another round of punishment from Washington.

The big takeaway: As Brideau's answers show, this summit isn't going to produce any breakthroughs — because it's not meant to. At best, it'll open a pathway toward a somewhat more "businesslike relationship" between two countries that are deeply at odds.

Stable and predictable? The relationship already is. It's just that it's stabley and predictably bad. Any improvement over that will be a win for both sides at Geneva.

- Biden-Putin summit: US wants predictability; G7's strong COVID ... ›

- Biden meets Putin: Much to discuss, little chance of progress ... ›

- Biden likely to push Putin on cybersecurity in Geneva meeting ... ›

- Putin' on a show for Biden - GZERO Media ›

- What to expect from Biden-Putin summit; Israel-Hamas tenuous ceasefire holds - GZERO Media ›

- Ukraine: Biggest foreign policy test for the Biden administration - GZERO Media ›

- Mikhail Gorbachev outlived his legacy - GZERO Media ›