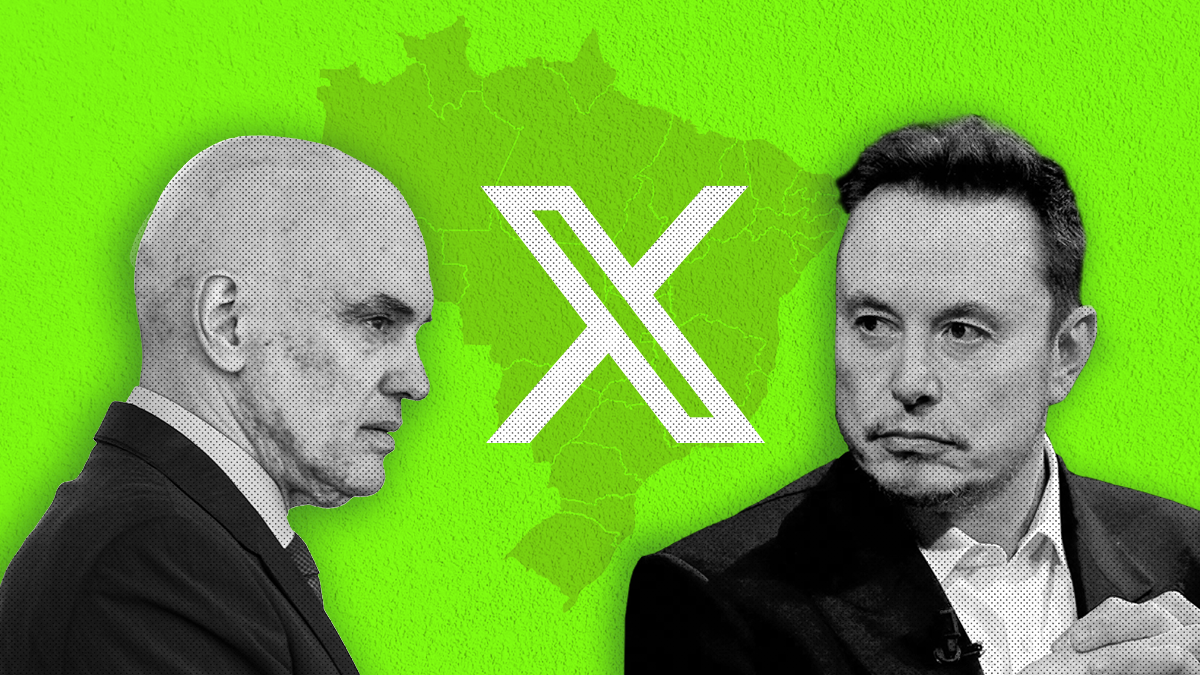

What on Earth is going on in Brazil? The world’s richest man, Elon Musk, is locked in a high-profile, increasingly nasty clash with Latin America’s largest economy, which has recently banned Musk’s X platform.

There are strong feelings and spicy memes. The X boss has accused his main opponent, Brazilian Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, of being “Voldemort” and “Darth Vader.” The dispute has even reached low-Earth orbit, ensnaring Musk’s Starlink satellites.

There are a few different ways to understand the spat – as a fight over speech, over sovereignty, or over egos. Each sheds light on a bigger issue in the increasingly fraught relationship between tech companies and national governments.

But first, the backstory.

For five years, Moraes has been investigating online disinformation and perceived online threats to Brazil’s democracy.

He has focused particular attention on accounts related, or sympathetic, to former President Jair Bolsonaro, the right-wing firebrand whose followers – whipped into a frenzy by (false) online allegations of vote rigging – ransacked Congress after he lost the 2022 election.

Moraes – whose prominent brow and perfectly bald pate do give him a bit of an Orlokian air, even if Voldemort is a stretch – has ordered raids on politicians’ homes, frozen their bank accounts, and even got Bolsonaro himself banned from politics for eight years.

His supporters say he’s fighting to protect democracy in an extremely online country that has a recent history of dictatorship. His critics say he’s playing loose with the law, overreaching, and pursuing an ideological agenda that suppresses free speech.

Enter Musk.

Not long ago, Moraes ordered X to suspend several popular accounts without naming them or explaining why. Musk, who now styles himself as a free speech defender (so long as he isn’t doing the defending in, say, India or Turkey, where he has complied with government demands to ban content), said the orders were illegal. He laid off a bunch of local staff rather than comply (while still leaving the service running).

Moraes, in turn, shut down X entirely in Brazil on the grounds that the company now lacked a local legal representative. As of a week ago, X no longer functions there. For X-ers in the rest of the world, the site has run extensive threads on what they say is Moraes’ overreach.

Ordinary Brazilians are split over the ban, but to be fair, X isn’t even among the top five social media apps in the country. (If you know Brazil, you know that if Moraes were to shut down, say, WhatsApp, there would either be a revolution or the country would simply evaporate in 24 hours.) Things could stay like this for a while.

So what’s this all about?

View one: It’s about speech! It’s no secret that governments around the world are grappling with the security and political stability implications of massive, unfiltered communications platforms where the velocity and reach of truth, lies, opinions, and cat memes is simply unprecedented.

“There’s a common thread of governments these days getting impatient with the platforms’ inability to self-police,” says Alexis Serfaty, a technology policy expert at Eurasia Group. “And they’re trying to act against a range of threats that they see, from public safety, to public health, and even to political stability.”

This explains X’s simultaneous legal battle with the EU over content moderation, as well as France’s charges against Telegram, which it accuses of prioritizing free speech over public safety and respect for local laws.

For a democracy, Brazil has especially expansive rules on what the government can try to root out – critics point out that the country now joins Russia, China, and Iran on the list of places where X is banned.

And if companies want to be there, they have to follow those rules, sure. But in the broader perspective, is the opaque policing of speech like this really the best way to preserve a democracy?

View two: It’s about sovereignty! Moraes has said as much. But this isn’t your grandad’s clash between multinational companies and national governments. The big global companies of yore – oil, mining, manufacturing – operated in a small number of sectors and had little direct contact with the public at large. Today’s tech firms, by contrast, shape the discourse, perceptions, politics, commerce, and even romances of billions of people globally all day, every day.

That’s a new kind of power – a very smart and well-known person I work with has dubbed it the “Technopolar world” – and we haven’t figured out yet what the balance of that power is.

View three: It’s about me! Moraes and Musk are two of the biggest egos on the planet. Part of this fight is personal, but not in the way you might think: Each of these men sees the outcome of this conflict as setting a big precedent.

“It’ll be interesting to see what happens in Brazil,” says Serfaty, “because I think if a government has success enforcing a specific action against a specific company – does that encourage more regulatory or other kinds of enforcement action in different countries? Does that kind of give them a little bit of momentum to push that forward?”

Should it? Where are the right lines between speech and safety, companies and countries? Let me know your thoughts here, and I’ll run some of the best responses in an upcoming mailbag.