October 10, 2024

Fewer than two weeks after Hurricane Helene devastated the southeastern United States, killing at least 230 people and causing billions of dollars in damage, Hurricane Milton hit Florida late Wednesday, causing multiple deaths, destroying homes, and bringing with it tornadoes, waves approaching 30 feet, and a thousand-year flood in the St. Petersburg area. Over 3 million in the state are without power. Before Milton made landfall, experts estimated the storm could cause between $50 and $175 billion in damage, with insurers on the hook for up to $100 billion.

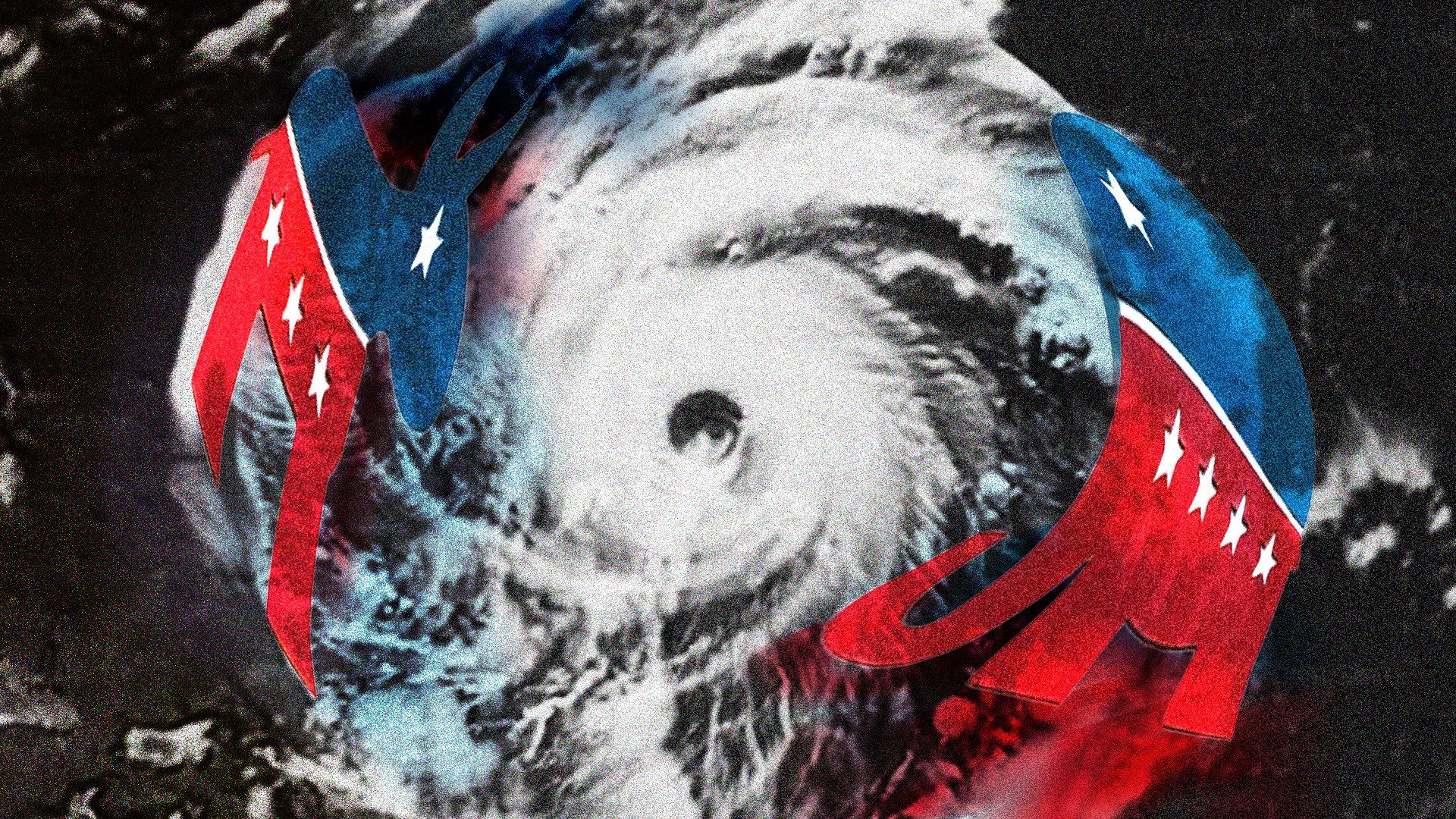

Meanwhile, the politics surrounding disaster relief has created a storm of its own. Republicans have criticized the Biden administration for not doing enough to help GOP-led states, while Democrats have blasted Republicans for wanting to cut federal disaster aid funding overall.

The acrimony spilled into the presidential race too, as Donald Trump made disputed claims that President Joe Biden hadn’t taken calls from Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, whose state was hit hard by Helene.

He also alleged, falsely, that his opponent, Kamala Harris, had spent “all her FEMA money, billions of dollars, on housing illegal immigrants.”

Meanwhile, on Monday and Tuesday, Harris and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis had their own squabble — DeSantis said he had refused to take calls from the veep because they seemed like a political setup. She, in turn, called him “selfish.” Still, DeSantis on Thursday praised the Biden administration’s overall disaster response.

And yet, in the midst of all the sniping, the Biden administration and Republican Governor Kemp seemed to be working together productively enough on relief efforts, with FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) doing its work on the ground while Biden visited Georgia and responded to requests to add counties to the disaster declaration list.

Is unity amid disaster possible?

Natural disasters are, ultimately, political: Preparations and the subsequent responses entail choices by politicians about money and resources, and the success or failure of plans can shape voters’ views of how competent, or not, their elected leaders are.

But as November’s presidential election looms, this kind of politicization is heightened.

Conor Frydenborg, an associate at Eurasia Group’s Energy, Climate, and Resources practice, says, “There is nothing in modern-day American politics that cannot be politicized” and warns that this is a potential impediment to rallying and uniting in the face of disaster.

“If something like 9/11, something like Hurricane Katrina, were to happen now, we are dealing with an environment where we really don’t think people can come together.”

One agency that is often at the center of these battles is FEMA, the main federal institution responsible for disaster relief, which controls a budget of roughly $33 billion. Some Republicans and Democrats are at odds over FEMA funding. Dozens of GOP members are demanding cuts to the agency’s migrant assistance budget — which has nothing to do with emergency disaster relief funds — and many voted against a recent $20 billion stopgap funding bill, which passed Congress nonetheless.

The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which has been described as a right-wing “blueprint” for a possible Trump White House, calls for privatizing some of FEMA’s work and shifting the bulk of the preparedness and response burden to state and local governments. It also calls for funding cuts to federal disaster grants and for state and local governments to pick up a larger part of the tab for relief efforts.

But is all politics national?

The national-level squabbling can sometimes obscure what’s happening on the ground, says Frydenborg.

For instance, in Georgia, in the aftermath of Helene, the governor’s reaction indicated that local, state, and national governments were coordinating and working well together.

“I would strongly assume that is because the governor of Georgia is primarily concerned with serving the people of Georgia and making sure that the infrastructure in the state is working correctly and people are getting the care that they need,” he says.

“So, if you want to see positive government action, look at what the local levels and the state level are doing. I think that it’s generally a more positive picture.”

More For You

- YouTube

At the 2026 World Economic Forum in Davos, GZERO’s Tony Maciulis spoke with Ariel Ekblaw, Founder of the Aurelia Institute, about how scaling up infrastructure in space could unlock transformative breakthroughs on Earth.

Most Popular

Haitian soldiers keep a watch outside the venue where businessman Laurent Saint-Cyr is set to be designated as president of Haiti's Transitional Presidential Council (CPT), in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, August 7, 2025.

REUTERS/Fildor Pq Egeder/File Photo

On Friday, US officials warned the transitional council in charge of Haiti not to remove interim Prime Minister Alix Didier Fils-Aimé, ahead of a deadline for the council to step down on Feb. 7.

Moldovan President Maia Sandu speaks during a Council of Europe diplomatic conference to launch the International Claims Commission for Ukraine, aimed at handling compensation claims related to Russia's war in Ukraine, in The Hague, Netherlands, December 16, 2025.

REUTERS/Piroschka van de Wouw

The president of the tiny eastern European country has suggested possibly merging with a neighbor.

Hard numbers: US pitches “New Gaza,” Japan paves way for snap elections, “Sinners” smashes records, & More

Jan 23, 2026

Middle East negotiator and son-in-law of President Trump, Jared Kushner talks with Israeli diplomats following a joint press conference in the State Dining Room of the White House in Washington, DC, USA, 29 September 2025.

$25 billion: The minimum amount of investment required to fulfil Jared Kushner’s ambitious property plan for Gaza.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.