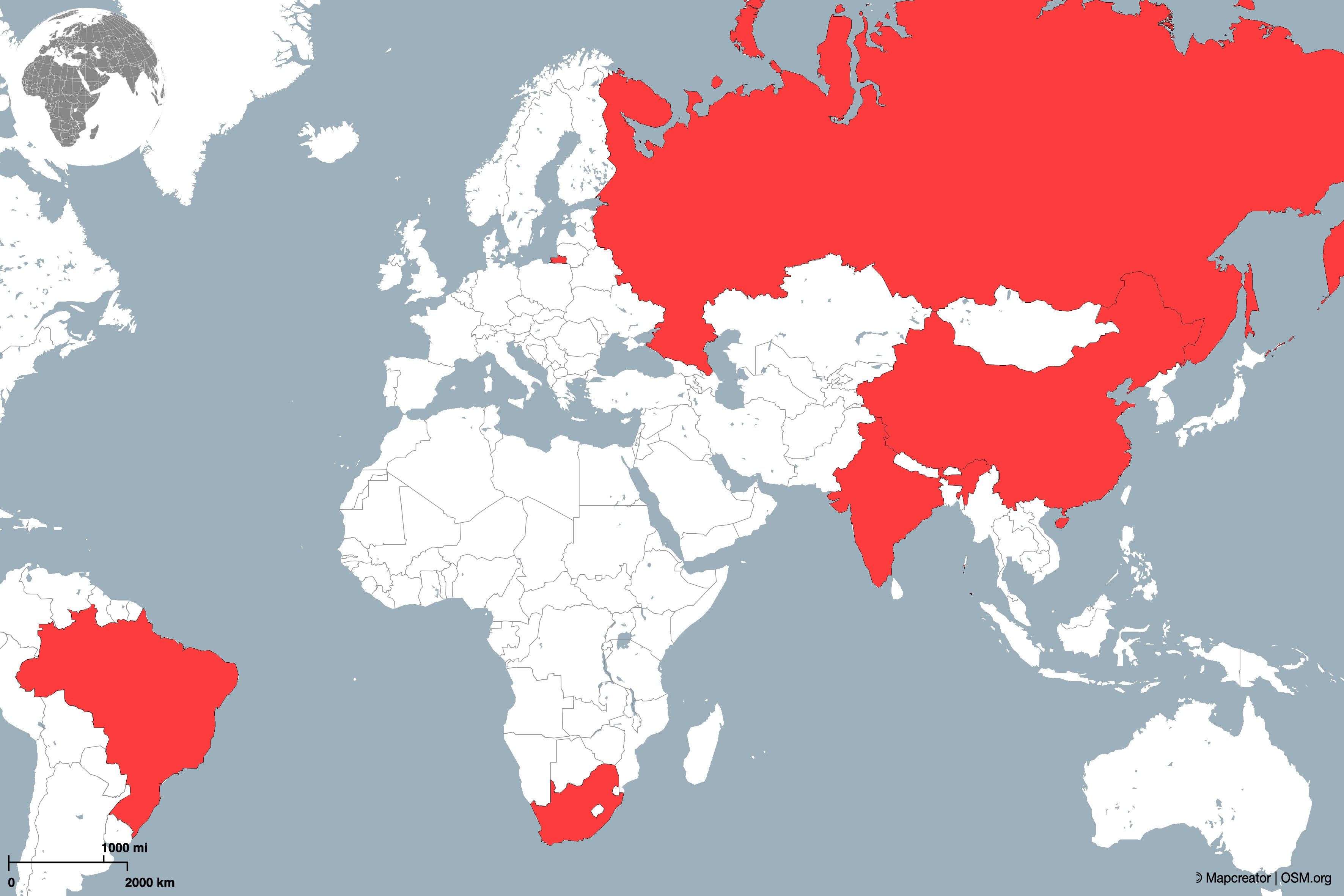

The BRICS grouping of five large developing countries will hold its annual summit from Aug. 22-24 in Johannesburg, South Africa, at a time of rising influence. Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa account for more than 25% of the world’s economic output and more than 40% of its population. Yet diverging national interests and broader geopolitical forces make it difficult for the bloc to act as a cohesive unit.

The potential for geopolitics to play a spoiler role was highlighted when the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to upend this week’s summit by putting South Africa in the awkward position of having to detain him if he were to attend. In the end, South Africa and Russia agreed that he would participate virtually.

We asked Eurasia Group experts Ali Wyne and Christine Hilt what to watch at the gathering.

Will there be any lingering fallout from the episode of Putin’s arrest warrant for Ukraine war crimes?

Only that Russia will not be able to advance its agenda as forcefully. Because South Africa was able to accommodate a hybrid format — with Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov attending in person — Russia will claim that its global relationships remain strong and that Western isolation efforts are failing. The West, however, will cite the format as evidence of Russian exclusion from international structures. Pretoria ultimately emerges as the primary winner; the summit will remain in South Africa, and the government managed to navigate the thorny issue of Russian attendance while also diffusing tensions with the US and other Western partners over its non-aligned position on the Russia-Ukraine war.

What are the main points on the agenda?

Potential BRICS expansion will be the most important issue. Although approximately 40 countries have formally applied for or expressed interest in membership, according to some media reports, BRICS members do not agree on how to move forward — a critical requirement for any final decisions. China is the most vocal proponent of expansion, viewing the BRICS as another prominent organization where it can increase its influence, support the growth of parallel international institutions, and counter the US. Russia is also on record as favoring expansion, as it seeks to promote alternatives to Western structures.

Brazil and South Africa are both concerned about diluting their own influence in the organization, while India’s primary concern remains China’s growing influence. Current messaging suggests that summit discussions will focus on establishing membership criteria, allowing reticent BRICS members to slow the expansion process down without being viewed as roadblocks.

Other agenda items will likely include current geopolitical issues, infrastructure development in emerging markets, and ongoing efforts to flesh out the structure and portfolio of the BRICS’ New Development Bank.

How will the Russia-Ukraine war affect discussions?

It has already had an impact, of course, with the controversy over the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant for Putin. Still, given that Russia is a member of the BRICS and that none of the other four members have sanctioned it, the war is unlikely to be a major topic of conversation at the summit. Since Putin will only be attending virtually, Moscow would not be well-positioned to propose a unified BRICS statement on the war; neither he nor Lavrov is likely to run the risk of presenting a statement that could be rebuffed.

China’s participation in peace talks in Saudi Arabia earlier this month has prompted some speculation that it may be tiring of Russia’s refusal to negotiate, especially as Russia was not invited to join. While Beijing wants to be seen as playing a constructive diplomatic role, there is little evidence that this effort includes any intention to recalibrate its relationship with Moscow.

How about the India-China rivalry?

This rivalry arguably does more to limit the cohesion of the BRICS than any other factor. And while India’s relationship with Russia is not as strained, Delhi worries about Moscow’s growing reliance on Beijing. India judges that China exercises growing sway over both the BRICS and another prominent grouping of countries, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, that observers see as a counterweight to Western influence. Delhi assesses that it can advance its national interests more effectively in fora where China is either not present or has a far less prominent voice, including the Quad (with the US, Australia, and Japan), I2U2 (with Israel, the UAE, and the US), and the G20.

What are Brazil’s and South Africa’s priorities?

Brazil has been focused on slowing down the expansion conversation; its concerns center on membership in what is seen as a pro-China organization and dilution of its influence. On Aug. 2, however, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva pushed back publicly on reporting that Brazil was the main holdout on including new countries and issued a more supportive statement on possible expansion. Given that China is making inroads to reduce Indian resistance to expansion, the Brazilians do not want to be seen as the sole holdouts. Their strategy will thus be to slow expansion and be very selective about who is admitted.

South Africa’s main priority for the summit will be to reaffirm its role as the key player on the African continent (hence this year’s theme, “BRICS and Africa”), including by potentially pushing for multilateral reforms that would give the African Union a permanent G20 seat (a possibility that will be on the agenda at next month’s G20 meeting in Delhi). Pretoria will also focus on increasing support for the NDB and obtaining agreements to support South Africa’s Just Transition and increased trade and development. It will likely seek to avoid significant discussion on security issues, hoping to mitigate Western concerns about its non-aligned position on the Russia-Ukraine war.

Given the current geopolitical environment, how do you expect the BRICS to evolve in the near to medium term?

The BRICS have never been — and are unlikely to become — a coherent geopolitical entity. The India-China rivalry is intensifying, and Brazil, India, and South Africa all wish to avoid the perception that the bloc is an anti-US counterweight. The group’s expansion prospects are uncertain, with only a few more countries likely to get in, and a BRICS common currency is unlikely to materialize in the near to medium term.

But the grouping’s influence should not be discounted. Its members have grown rapidly since economist Jim O’Neil coined the term “BRIC” in 2001 (the group expanded to include South Africa in December 2010), especially China and India, whose GDPs have doubled over the past decade. While China and Russia are the most vocally opposed to US influence, all five seek to promote a more multipolar international system and reduce the centrality of the US dollar in global finance. And if one takes a wider aperture — considering not only the bloc’s potential expansion but also the incorporation of Iran into the SCO and the growing sway of “swing states” such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey — one sees the emergence of an international system in which the Global South and middle powers will wield steadily more geopolitical heft.

Edited by Jonathan House, Senior Editor at Eurasia Group