August 31, 2023

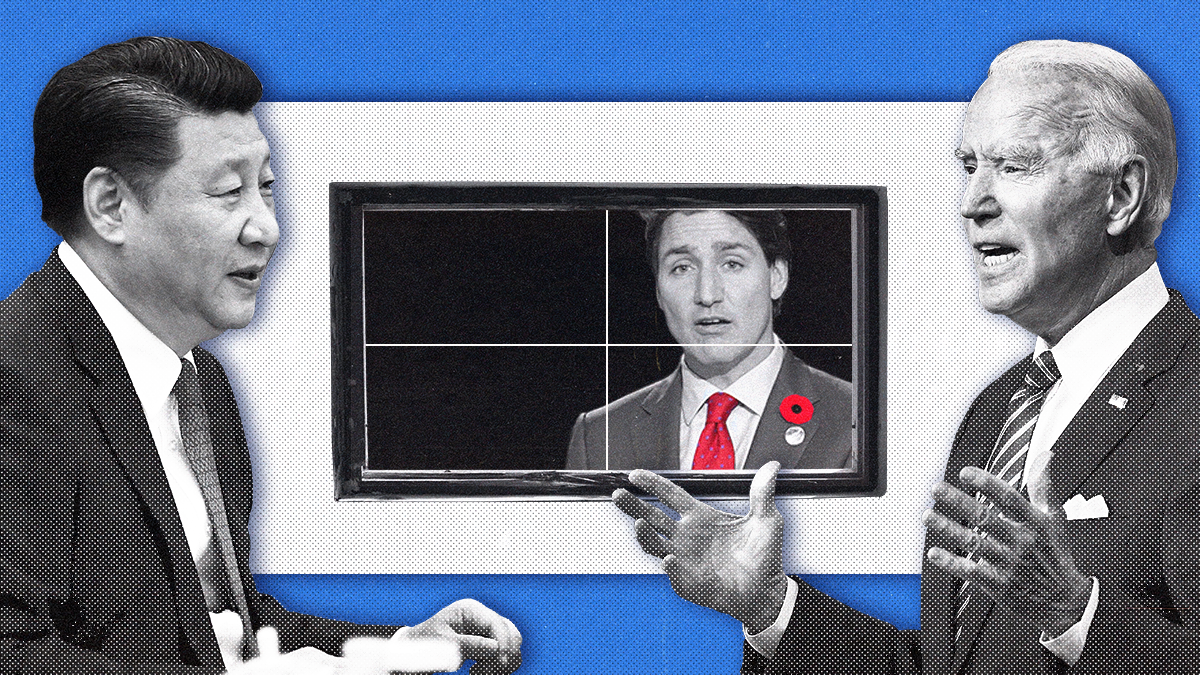

A breakthrough in US-China relations is signaling a possible detente. Earlier this week, US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo visited her counterpart Wang Wentao in Beijing to discuss smoothing trade relations. While the Biden administration is still committed to trade and security restrictions on China, it’s hoping to open space for more trade on consumer goods while “de-risking” the relationship between the countries – meaning reducing the chances of an accident or misunderstanding escalating into a full-blown crisis. For its part, Canada, as always, is following in the wake of the big powers.

Why now?

China’s economy is slowing of late, putting pressure on Xi Jinping. Chinese exports were down 14.5% year on year in July, while imports were down 12.4%, and economic growth between April and June was down to 0.8%. Trade with the US, meanwhile, is down 34%.

Between China’s economic slowdown and the Biden administration’s desire to de-risk and stabilize relations, there’s now an opportunity for the two to build a little trust in a relationship long marked by distrust – but that doesn’t mean sunshine and rainbows. As Anna Ashton, a China expert at Eurasia Group, warns, this reset is not a return to US-China relations pre-Trump. “It’s not a detente that is aimed at ending the competition between the two countries or resolving ideological differences, or rectifying concerns about national security. It’s something else.”

That “something else” may be a smoother and more responsible sort of competition. “It’s like we’re in this chapter of both sides recognizing each other as rivals and potential adversaries,” says Ashton. But they’re also acknowledging the mutual need to have clear channels of communication and engage in crisis prevention. “I find that unexpected,” she says, describing the relationship as “rivalrous and constructive at the same time.”

And what about Canada?

Canada-China relations are currently rocky, at best, and some say they’ve reached “an all-time low.” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is facing pressure to call an inquiry into alleged Chinese electoral interference – despite special rapporteur, former Governor General David Johnston, recommending against one. Johnston warned of subversive threats to Canadian democracy from foreign interference but said little to no evidence was found to support allegations that China had directly funded candidates in the 2019 Canadian election or targeted candidates for defeat. He also found no evidence that former Liberal MP Han Dong had interfered in the process to secure the release of two Canadians, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, arrested by China. Dong left the party’s caucus over the allegations but is now seeking to return, having been vindicated by the report.

So, given these tensions, where does the US reset with China leave its northern neighbor? Canada is one of America’s top three trading partners, alongside Mexico and China, with nearly $8oo billion in trade between the two countries in 2022. Trudeau will be watching Biden’s China policy closely and keeping tabs on how the 2024 election takes shape. Canada struggled to deal with the Trump administration during its tenure, cursed with managing both the mercurial president and traditional trade challenges such as softwood lumber disputes.

As president, Trump forced a long, difficult renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement – now the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement. Last month, former US trade representative Robert Lighthizer revealed in his memoir “No Trade Is Free,” that during that time, the relationship between the two countries sunk to its lowest since the War of 1812. History buffs may remember that war as the one where the British, who claimed and governed Canada as its territory at the time, set the White House on fire – so it’s a high bar for low relations.

The magical powers of supply chain security

If Canadians are worried about what Biden’s rapprochement with China means for them, they may be buoyed by the administration’s desire to secure its critical supply chains. Graeme Thompson, senior analyst of global macro-geopolitics at Eurasia Group, says that while the president is making space for more trade with China on consumer goods, Canada remains a trusted ally – especially when it comes to sensitive trade goods.

“Canada is already treated as, essentially, a domestic source for US military procurement, and it benefits from measures in the US Inflation Reduction Act that incentivize electric vehicle manufacturing and cross-border supply chains within North America,” he says. The two countries are particularly close on critical mineral trade and trade related to technologies with national security implications, such as microprocessors. Still, Canada is left to shape its policy to conform to American imperatives – and that includes not being too far out of step in its relationship with China as the Biden White House seeks a more stable relationship with Beijing.

Ottawa in the middle

Canada is caught between the US and China and left responding to events rather than shaping them – and that's not a new problem. This conundrum was exemplified by the Meng Wanzhou affair, in which Canada arrested the Huawei executive (and daughter of the company’s founder) at Washington’s request, which prompted China to arrest the two Michaels (mentioned above) and charge them with espionage. The men were freed the day Meng was released with a deferred prosecution agreement negotiated by US prosecutors.

Once again, Canada has plenty of work to do now to warm up its own relationship with China and to follow the American lead on trade policy. As Thompson puts it, when it comes to choosing sides and trade relations, “There isn’t really much choice for Canadian policymakers – the option is to stay closely aligned to the US, and the alternatives aren’t readily apparent.”

As concerns over supply chain security and reliability persist, it makes sense that the US and Canada, long-term trusted allies and neighbors, would keep close, even while Biden attempts to de-risk relations with China. That’s good news for Canada. But at the same time, the White House is seeking to break with past Democratic presidents – Obama and Clinton – to focus more on protecting American workers, which further puts pressure on Canada as it struggles to get its share of the American manufacturing and trade pie.

The break with past trade and industrial policy means more goods manufactured in the US and a more closed economy. It also means putting a bit of a brake on globalization. Policies and laws such as the IRA, The Build America, Buy America Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act include protectionist provisions and reflect the president’s home-first focus. But the securing of supply chains may still be a boon for Canada despite a more isolationist American bent.

Canada should still have a significant role to play in the US economy – and not just for consumer goods. “There’s a lot of talk of re-shoring, but also near-shoring and friend-shoring,” says Thompson. “While American policymakers want to bring jobs and production home to the US, having strategic supply chains run through close security partners and allies is an acceptable second best. And because of geographic proximity, an intimate security and defense relationship, and what Canada sells into the market, all of those things put Canada in a very strong position to capitalize on US concerns about supply chains.”

Between navigating a response to the US-China detente and America-first policies, Canadian trade and foreign policy folks have their work cut out for them – but with both countries facing elections, it’s unclear how long they have to maneuver.

The electoral factor

National votes are pending in the US in 2024 and Canada in 2025, and campaign politics have a way of changing the diplomatic mood. In recent weeks, Canadian Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault, for example, caught heat from opposition Conservatives for heading to China to discuss climate change.

In the US, there are calls from both sides of the aisle to toughen relations with China. “There’s far more political incentive to be hawkish than anything but hawkish,” Ashton says.

So while both Biden and Trudeau are currently pushing for better relationships with China and cooperation on critical shared problems such as climate change, things could change quickly as elections loom. As always, politics comes first.

More For You

Most Popular

Alysa Liu of Team USA during Women Single Skating Short Program team event at the Winter Olympic Games in Milano Cortina, Italy, on February 6, 2026.

Raniero Corbelletti/AFLO

Brazilian skiers, American ICE agents, Israeli bobsledders – this is just a smattering of the fascinating characters that will be present at this year’s Winter Olympics. Yet the focus will be a different country, one that isn’t formally competing: Russia.

What We’re Watching: Big week for elections, US and China make trade deals, Suicide bombing in Pakistan

Feb 06, 2026

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), appeals for a candidate during a street speech of the House of Representatives Election Campaign in Shintomi Town, Miyazaki Prefecture on February 6, 2026. The Lower House election will feature voting and counting on February 8th.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Japanese voters head to the polls on Sunday in a snap election for the national legislature’s lower house, called just three months into Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s tenure.

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.