August 25, 2021

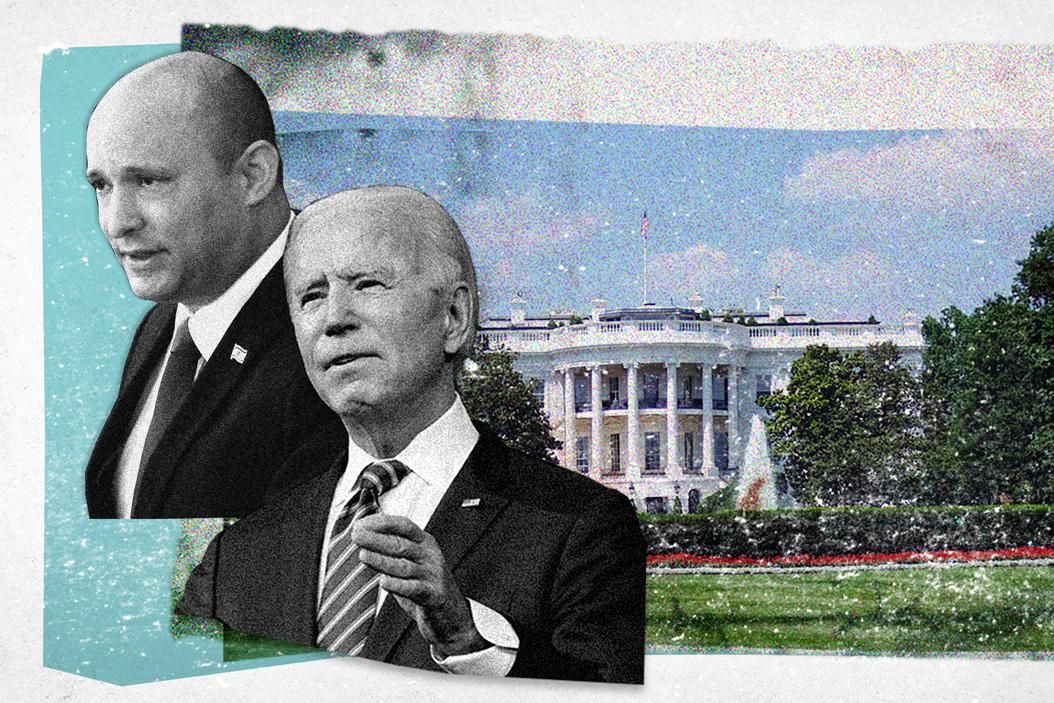

For the first time since assuming their posts, Israel's right-wing Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and US President Joe Biden will meet Friday for a face-to-face meeting at the White House. (Fun fact: Joe Biden was elected to the US Senate in 1972, the year Naftali Bennett was born.)

What's on the agenda — what likely isn't — and why does this meeting matter now?

Iran, obviously. Bennett may embrace a more conciliatory tone than his predecessor Bibi Netanyahu, but when it comes to Iran policy, he too thinks that a return to the nuclear deal would be catastrophic for Israel. For the Israelis, delivering that message feels all the more pressing given that their security establishment now warns that Tehran is only two months away from being able to produce a nuclear weapon.

So, what's President Biden's view? Well, Biden is still adamant that a return to the JCPOA — the nuclear agreement agreed to in 2015 by Iran along with China, France, Germany, Russia, the UK, and the US — is a foreign policy priority. Biden remained gung-ho as recently as June when relevant players met in Vienna to chart a path forward.

But that was before the fiasco in Afghanistan, which has thrown the Biden administration, and its foreign policy agenda more broadly, into disarray. Indeed, after the bungled withdrawal it's entirely possible that the US will want to stall on the Iran negotiations, which remain in limbo. After all, it would be a PR calamity for the stalemate with the Iranians to be back in the news while the debacle in Afghanistan — which seems unlikely to be resolved anytime soon — continues.

However, even if Biden does suspend or slow roll talks, that's still unlikely to placate the Israelis, who are worried that the Iranians will further develop their nuclear program while the US and Europeans are distracted with Kabul.

While Bennett doesn't want a new nuclear deal, he might prefer the certainty of that to the limbo of a Biden White House that is stalling Iran talks in order to buy time to recover from the Afghanistan chaos. At least then Israel could prepare for what comes next.

Though details remain scarce, Bennett reportedly plans to present an alternative to the JCPOA that also addresses Iran's destabilizing activities in the region, and is also expected to ask Washington for more funds to bolster its military capabilities against Iran and its proxy forces.

The China equation. Few people think of China as a wedge issue in US-Israel relations. But in recent years, it's emerged as a point of friction.

Israel, for its part, has been trying to bolster economic ties with Beijing for years, seeking increased Chinese investment in Israeli infrastructure and technology. But as Washington increasingly sees Beijing as its main rival, it has put pressure on the Israelis to temper cooperation with the Chinese. For example, after Washington scolded the Israelis for signing a contract with a Chinese firm to operate a private shipping seaport off Haifa's port, Israel turned down a Hong Kong firm's bid to develop a water desalination plant worth a whopping $1.5 billion.

In a sign of how pressing the issue is for the Americans, CIA Director Bill Burns raised China concerns directly with PM Bennett on a recent visit to Israel, after a Chinese company won a tender for a massive transportation project in the Tel Aviv metro area.

What's not really on the agenda? The Palestinians. While the Biden administration may pay lip service to to the Palestinian cause, the moribund peace process is unlikely to occupy much time at all. This suits both Biden and Bennett just fine: the US president has made clear that he is focused on making domestic gains, particularly ahead of midterm elections next year. Meanwhile, Bennett, who heads to Washington amid a flareup of violence on the Gaza border, heads an ideologically-diverse coalition government that has all but agreed not to touch the Palestinian issue.

Give and take. Some analysts have suggested that Bennett could offer to take in a small number of Afghan refugees as a goodwill gesture to a beleaguered Biden — similar to when Menachem Begin accepted 370 Vietnamese refugees in the late 1970s after the fall of Saigon. While that might boost mutual confidence in the short term, it's unlikely to significantly move the needle on these extremely thorny issues.

From Your Site Articles

More For You

Hellenic coast guard performs SAR operation, following migrant's boat collision with coast guard off the Aegean island of Chios, near Mersinidi, Greece, February 4, 2026.

REUTERS/Konstantinos Anagnostou

15: The number of migrants who died after their boat accidentally collided with a Greek Coast Guard vessel in the Aegean Sea on Tuesday. Two dozen people were rescued.

Most Popular

Walmart is investing $350 billion in US manufacturing. Over two-thirds of the products Walmart buys are made, grown, or assembled in America, like healthy dried fruit from The Ugly Co. The sustainable fruit is sourced directly from fourth-generation farmers in Farmersville, California, and delivered to your neighborhood Walmart shelves. Discover how Walmart's investment is supporting communities and fueling jobs across the nation.

Workers repair a pipe at a compound of Darnytsia Thermal Power Plant which was heavily damaged by recent Russian missile and drone strikes, amid Russia's attack on Ukraine, in Kyiv, Ukraine February 4, 2026.

REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko

Democratic Alliance leader John Steenhuisen announced Wednesday that he will not run for a third term as leader of the liberal, pro-business party, after months of internal pressure over a host of controversies – including allegations, since cleared, that he used the party credit card for Uber Eats.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.