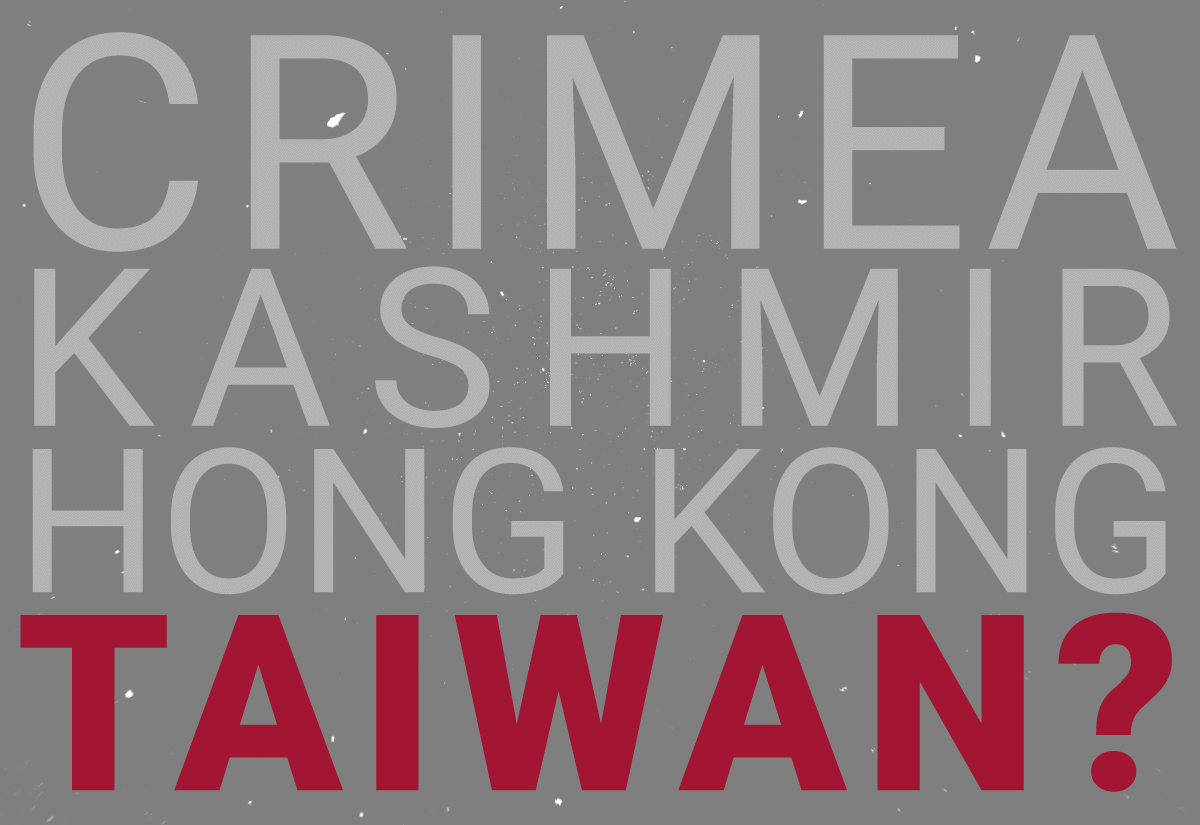

Over the past few years, we've seen three major emerging powers take bold action to right what they say are historical wrongs.

First came Crimea. When the Kremlin decided in 2014 that Western powers were working against Russian interests in Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin ordered Russian troops to seize the Crimean Peninsula, which was then part of Ukraine. Moscow claimed that Crimea and its ethnic Russian majority had been part of the Russian Empire for centuries until a shameful deal in 1954 made Crimea part of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. Americans and Europeans imposed sanctions on Russia. But Ukraine is not part of NATO or the EU, and no further action was taken.

Then came Kashmir. Kashmir has long been divided into Indian- and Pakistani-administered sections separated by a "line of control." The two countries have come to blows over Kashmir several times, and some Kashmiris want independence from both. Indian-administered Kashmir has the only Muslim-majority population on Indian territory, and to manage the resulting tensions, Article 370 of India's constitution gave the territory its own constitution and flag — and the right to make its own laws in areas that don't concern India's defense or foreign policy. After years of periodic unrest and insurgency in the province, Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered Indian troops into the province in August 2019, and India formally revoked Kashmir's autonomy.

Now comes Hong Kong. When Hong Kong passed from British to Chinese authority in 1997, Beijing agreed to respect a plan known as "one country two systems," which allowed the territory to make its own laws, in areas that don't affect China's defense or foreign policy, and to keep its own police force. Freedoms of speech and the media remained in place. After a proposed law that would allow Hong Kongers to be extradited to face trial on the mainland triggered a tidal wave of unrest across the city, Beijing imposed a new security law that undermines basic freedoms in Hong Kong, and would make it illegal for literally anyone on Earth to promote democracy for its people. Without sending in troops, Beijing effectively ended Hong Kong's autonomy.

These three cases have something basic in common, despite their dozens of differences. All involve powerful emerging states — Russia, India, and China — with nationalist leaders who used historical claims to seize control of territory they believed rightfully belonged to their countries. And all did so secure in the knowledge that no outside power, or alliance of powers, would be willing and able to stop them.

So, who's next? Successive Chinese leaders, including current president Xi Jinping, have made clear that they believe Taiwan is part of China and will one day return to Beijing's control.

In 1996, China fired ballistic missiles into the sea to intimidate Taiwan, and President Bill Clinton responded by ordering two US aircraft carriers into the Taiwan Strait to send Beijing a message. China backed down. That was 24 years ago. Since then, China has spent trillions to modernize its military and to equip it with 21st century weapons. In Asia, at least, the military balance of power has changed.

Taiwan isn't Crimea, Kashmir or Hong Kong. It's a wealthy country of 24 million people, that is very well armed (by the US).

But if China fired missiles toward Taiwan today, how would outsiders respond? If the US president flexed America's military muscle, would China's leaders back down? What if they didn't?

And for how much longer will this question remain hypothetical?