China's GDP grew a lower-than-expected 4.9 percent year-on-year in the third quarter of 2021, a whopping three percentage points less than in the previous period. It's a big deal for the world's second-largest economy, the only major one that expanded throughout the pandemic — and now at risk of missing its growth target of 6 percent for the entire year.

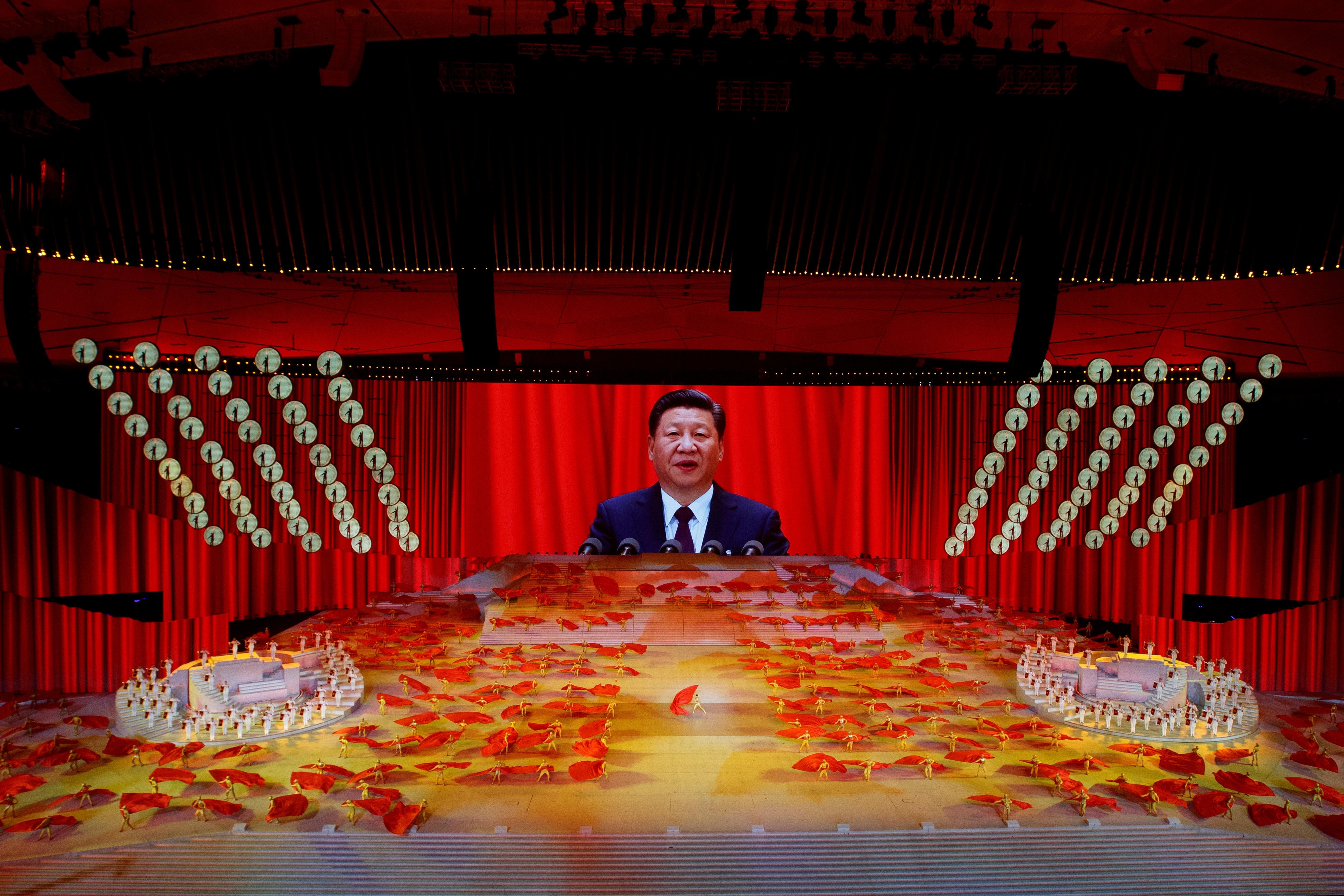

Normally, such a drastic slowdown would have put the ruling Communist Party in a tizzy. But this time, Xi Jinping knows this is the price he must pay for his big plans to curb rising inequality and boost the middle class at the expense of the CCP's traditional economic mantra: high growth above all else.

Why is GDP growth slowing down now? For one thing, a combination of rising coal prices, tighter regulations on power consumption related to climate policy, and soaring demand in countries that buy a lot of Chinese-made stuff have all resulted in an energy crunch that'll likely worsen disruptions to global supply chains that rely heavily on China.

For another, Xi's crackdown on excessive borrowing in the real estate sector — which accounts for almost 30 percent of China's economic activity but was so in the red that it posed a systemic risk — is causing a lot of pain. Evergrande and other large property developers are missing deadlines to pay their creditors, and halting projects for homes they've already sold but have no money to build.

Finally, there's the pandemic itself, via strict local lockdowns that have hurt Chinese retail and travel in the only country in the world that still believes in zero COVID.

China's leader thinks that an economic slowdown, however painful in the short term, will be worth it in the long run because the economy needs structural reforms to narrow the income gap and deliver what Xi calls "common prosperity."

In a speech that stunned the business community two months ago, Xi confirmed that "common prosperity" means vastly expanding China's middle class, partly by raising taxes on the rich. He wants some of this wealth to be redistributed in order to make China a more equal society. (Indeed, the 1 percent have seen the writing on the wall — a single mention of regulating "excessively high incomes" prompted several panicked CEOs to immediately donate billions to charity right when Xi was going after the tech sector.)

Xi's goal is for China's GDP to continue expanding, but at a less ambitious pace so Chinese workers have time to earn more and become more productive at the same time. China, he says, should move away from mostly churning out cheap exports that pollute the planet as Chinese factories have done for decades to focus on producing high-quality, sustainably-made goods for the local market.

But it's a risky move. Winding down economic activity to the 2-3 percent annual growth levels of mature economies like the US or Germany will be a tricky balancing act for China. Sluggish growth that drags on could deter investment, and trigger social unrest if unemployment gets too high as a result.

Meanwhile, slower Chinese economic growth will have serious ripple effects for the rest of the world, given China's outsize role in the global economy.

The so-called "factory of the world" will probably continue exporting a lot of stuff, but not as much as it did before, and more of its exports will be high-value tech goods. Local companies will also likely outsource more of their manufacturing to lower-cost neighbors such as Bangladesh or Myanmar, and over time most Chinese-made products will get more expensive.

Xi's "common prosperity" vision comes with many risks for China's juggernaut of an economy. But if he delivers on his promise, expect him to stay in power for a long time.- Why is Xi Jinping lurking in bedrooms? - GZERO Media ›

- Can Xi save China from Evergrande? - GZERO Media ›

- The Graphic Truth: China's growing share of the world economy ... ›

- China has a big population problem - GZERO Media ›

- The Graphic Truth: This day dwarfs Black Friday - GZERO Media ›

- Why is Xi Jinping lurking in bedrooms? - GZERO Media ›

- Kevin Rudd: COVID has made Xi Jinping zero-risk - GZERO Media ›

- Ian Explains: Why China’s era of high growth is over - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: China's great economic slowdown - GZERO Media ›

- Davos 2024: China, AI & key topics dominating at the World Economic Forum ›

- China's economic slowdown is dragging down the rest of the world - GZERO Media ›

- Are the US and China frenemies now? Perspective from Nicholas Burns, US Ambassador to China - GZERO Media ›

- North Macedonia's EU membership bid complicated by new nationalist government - GZERO Media ›

- Why China is leading economically: infrastructure, energy, & tech - GZERO Media ›

- Will China determine the fate of the world? - GZERO Media ›

- Beating China at AI - GZERO Media ›

More For You

In this Quick Take, Ian Bremmer weighs in on the politicization of the Olympics after comments by Team USA freestyle skier Hunter Hess sparked backlash about patriotism and national representation.

Most Popular

100 million: The number of people expected to watch the Super Bowl halftime performance with Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican superstar and newly minted Album of the Year winner at the Grammys.

Brazilian skiers, American ICE agents, Israeli bobsledders – this is just a smattering of the fascinating characters that will be present at this year’s Winter Olympics. Yet the focus will be a different country, one that isn’t formally competing: Russia.

What We’re Watching: Big week for elections, US and China make trade deals, Suicide bombing in Pakistan

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), appeals for a candidate during a street speech of the House of Representatives Election Campaign in Shintomi Town, Miyazaki Prefecture on February 6, 2026. The Lower House election will feature voting and counting on February 8th.

Japanese voters head to the polls on Sunday in a snap election for the national legislature’s lower house, called just three months into Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s tenure.