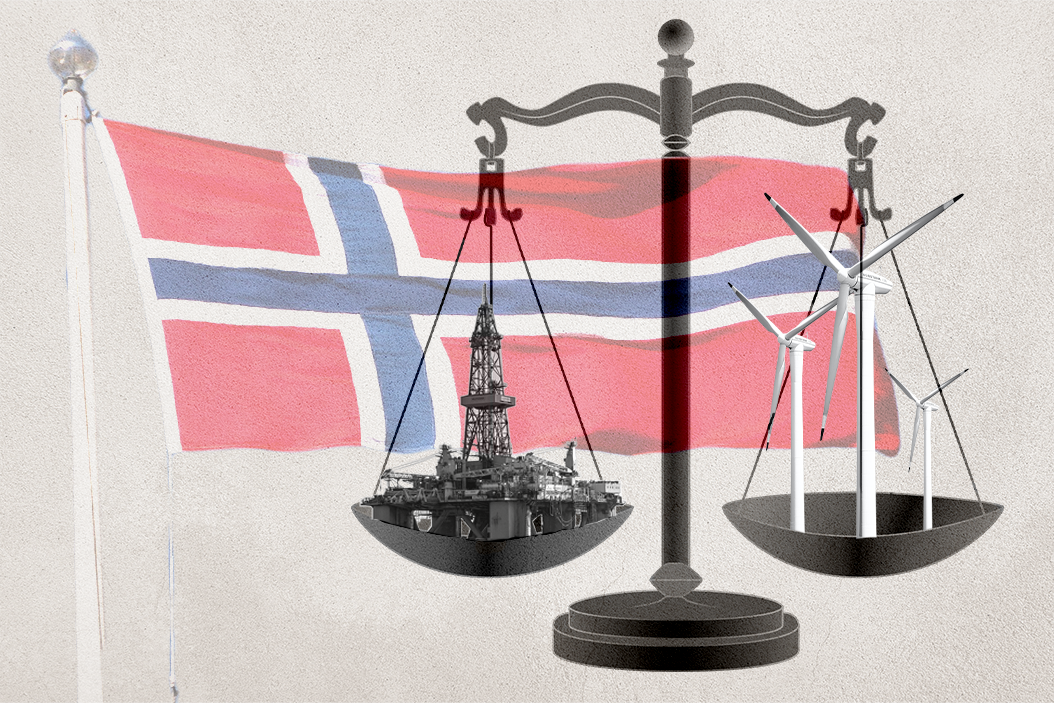

What do you do when the thing that has helped to make you a rich, prosperous, and healthy democracy is also destroying the planet that you want to save? That's the choice before the roughly five million people of Norway as they head into a pivotal election on September 13.

No industrialized, competitive democracy is quite as dependent on fossil fuel exports as Norway. The discovery of oil and gas reserves in the North Sea half a century ago catapulted the country from a tidy but small fishing and timber economy to one of the most advanced and prosperous social welfare states on Earth.

Oil accounts for more than 40 percent of Norway's exports. The industry employs some 200,000 people directly, or about 7 percent of the workforce. And of course, Norway's famed, oil-fueled sovereign wealth fund is the world's largest, clocking in at more than a trillion-dollars. While it funds pensions -- rather than the budget, which is financed through typically high Nordic taxes -- the sovereign wealth fund is a nest egg (and crisis cushion) that most countries can only dream of.

At the same time, Norway is a green country that wants to be a leader in global efforts to combat climate change. How is this possible? For all the oil and gas that it ships abroad, Norway uses barely any of the stuff at home. The vast majority of Norway's electricity generation comes from hydropower, not hydrocarbons. Seven in ten new vehicles sold there last month were fully electric. Most of the capital, Oslo, is entirely and pleasantly car-free now.

But activists and upstart political parties are now drawing a closer connection between Norway's economic model and its environmental goals. And this contradiction — fossil-fuel dependency and green ambition — is now on the ballot.

The two establishment parties, the flagging center-right Conservatives who currently hold power, as well as the frontrunner center-left Labour opposition, stand behind the industry. They say that while they favor a gradual transition away from fossil-fuel production, the economic consequences of pulling the plug too quickly would be devastating.

They also point out that even if Norway stopped selling oil, it would have little impact on the climate unless global demand for the stuff goes down more broadly; that is, if we don't sell it to an oil-thirsty world, someone else will simply take our place.

But here's the thing: Labour is currently leading polls, but at just 23 percent it would have to form a coalition to govern. And two of its most natural possible partners, the leftwing Socialist Left Party (10 percent) or potentially the center-left Greens (5 percent), want to halt new exploration licenses. The Greens want to stop production altogether by 2035, and say they won't form a coalition with any party that opposes banning exploration immediately. "Our demand is absolute," party energy spokesman Ask Ibsen Lindal told GZERO Media.

In fact, the traditional parties in Norway are on their back foot generally these days. In midterm municipal elections in 2019, voters "gave the finger" to the establishment, ringing up big boosts not only for the Greens and parties on the hard left, but also to the agrarian Center Party and a pro-motorist group called PNB, which opposes environmental and road taxes.

All of this means that there could be a fragmented and potentially inconclusive election outcome. And the stakes couldn't be higher. Half a century ago Norway pulled off one of the most radical, rapid, and successful economic transformations in modern history. But today climate change is forcing the country to reckon with the idea of giving a lot of that up. Can Norway's fractious politics meet the urgency of the moment?- Norway's school phone ban aims to reclaim "stolen focus", says PM Jonas Støre - GZERO Media ›

- Solving Europe's energy crisis with Norway's power - GZERO Media ›

- Norway's PM Jonas Støre says his country can power Europe - GZERO Media ›

- Europe's energy future: Perspective from Norway's PM Jonas Støre - GZERO Media ›

More For You

100 million: The number of people expected to watch the Super Bowl halftime performance with Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican superstar and newly minted Album of the Year winner at the Grammys.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

An imminent US airstrike on iran is not only possible, it's probable.

Americans are moving less — and renting more. Cooling migration and rising vacancy rates, especially across the Sunbelt, have flattened rent growth and given renters new leverage. For many lower-income households, that relief is beginning to show up in discretionary spending. Explore what's changing in US housing by subscribing to Bank of America Institute.