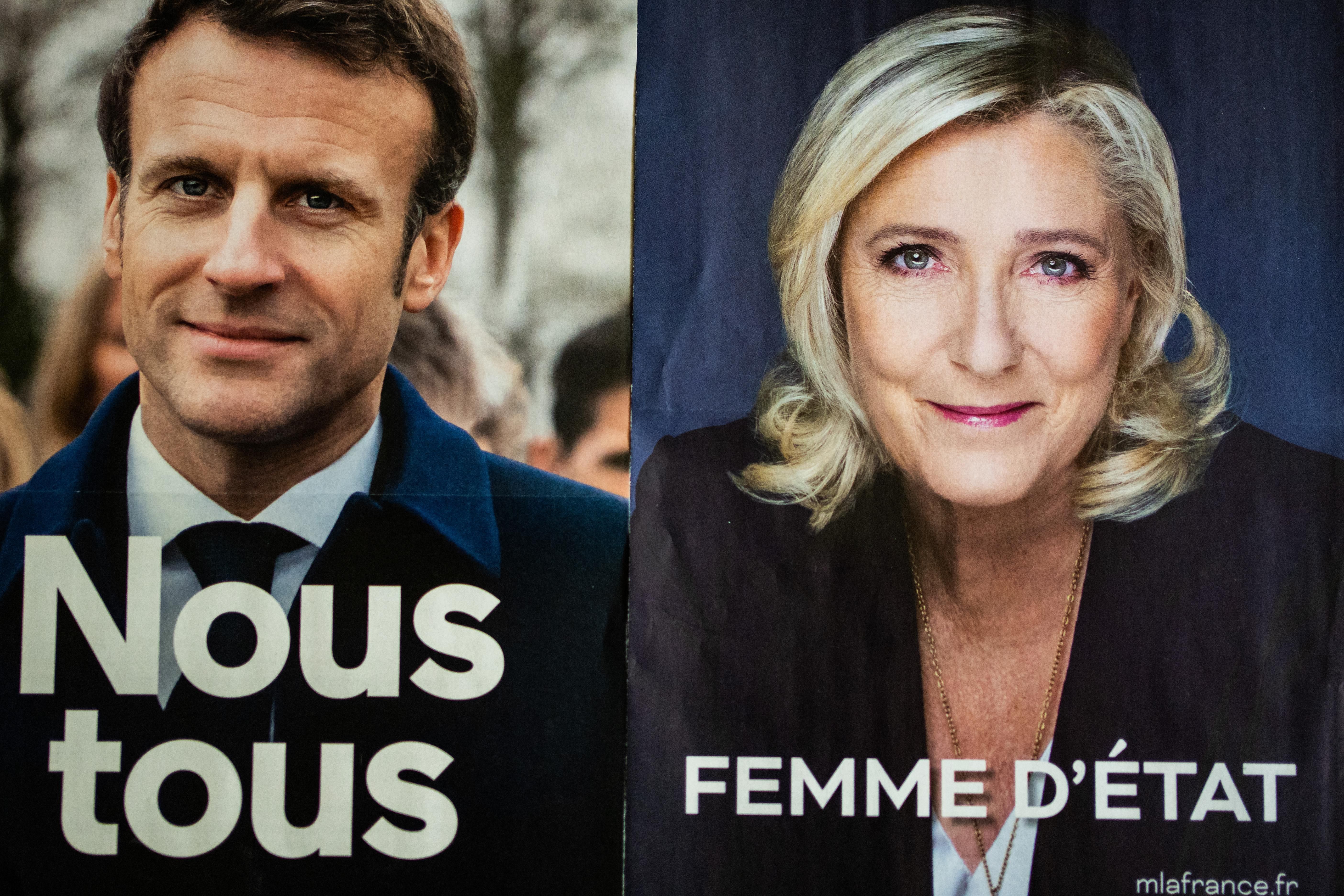

The results are in from the first round of France’s nail-biter of a presidential election. Marine Le Pen, head of the far-right National Rally, has come in four points behind the incumbent, President Emmanuel Macron, reaping 23.3% percent of the vote, according to Ifop, a pollster.

Meanwhile, France’s far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon came in third with 20% of the vote, while center-right candidate Valerie Pécresse, the first woman to head the party of Charles de Gaulle, flailed.

The world is now anxiously waiting to see what happens in two weeks’ time, when the French return to the polls for the second and final round of voting to decide whether Macron or Le Pen should be sent to the Élysée.

Le Pen, a veteran politician, has run for the presidency twice before, but her political career, it seems, has all been leading up to this moment. Indeed, she trails Macron by a few points, but the momentum is very much on the side of the 53-year old, whose “France first” message has resonated not only with tear-it-down populists, but with ordinary families angry about the soaring cost of living.

What would a Le Pen victory actually mean for France, Europe – and the world?

Le Pen: not great for French unity. Le Pen has worked hard to moderate her far-right sensibilities. She’s talked less about Muslims and banning headscarves in recent months, focusing more on the increasing price of milk and eggs.

Still, her domestic political priorities remain unchanged. Mujtaba Rahman, head of Eurasia Group’s Europe desk, says Le Pen "is no more moderate or reasonable today than she has been historically. She remains an extreme right force in French politics.”

The immediate stakes are extremely high for the European Union, which has experienced a renewed sense of purpose since the UK left the bloc in 2020 and especially in response to Russia’s bombardment of Ukraine.

Le Pen, a long-time euroskeptic, has tried to moderate her views to appeal to a Russian-weary French electorate that overwhelmingly supports EU efforts to aid Ukraine. Still, Le Pen is no fan of Brussels and maintains that the bloc’s central power should be diluted.

While she seems to have abandoned her previous call for France to leave the EU – dubbed Frexit – some believe Le Pen may be gunning for a more digestible overhaul of the relationship. Ben Judah, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, says Le Pen may pursue something similar to what the Poles have been doing. “What Poland is doing is attempting to renegotiate its relationship with the EU by insisting that national law is supreme over EU law,” he says.

What’s more, the stakes for the European single market are mammoth. The prospect of a Le Pen victory is a big blow for EU champions who have been buoyed by the EU’s renewed financial cohesion amid the pandemic, having overcome longtime sticking points to approve a robust economic recovery fund.

However, European heavyweights, like Germany, might reject sharing meaningful common debt with a France run by Le Pen, whose economic policy Judah describes as “gibberish.” If Le Pen gets in and implements her economic plan – which includes renegotiating a slate of free trade deals – this would mean that “making the euro a really strong, efficient currency is just going to be off the table” he says.

More broadly, a Le Pen victory in France, the world’s sixth-largest economy, would send a worrying message to the world about the country’s commitment to liberal values.

Le Pen comes from a xenophobic tradition established by her father Jean-Marie, a prominent racist and antisemite. Many members of her party are racist, and she has been accused of harboring anti-Muslim sentiments. Even though Le Pen has tried to detoxify her image, many older voters – and global observers – aren’t buying the rebrand.

A Le Pen presidency would have a big impact on how France “is seen by American liberals, by Arab and non-white countries, and across the Muslim world,” Judah says. This, he adds, could destroy the credibility built up by Macron, who has tried to position himself as Angela Merkel’s successor as the leader of Europe in recent months.

The Ukraine factor. Macron has long been a proponent of greater European strategic autonomy and in recent months has called for a united Europe to engage with Russia separately from the broader US-NATO dialogue. His shuttle diplomacy with Vladimir Putin has boosted his image as an international statesman.

Le Pen, on the other hand, is avowedly anti-NATO and says she wants to pull French troops and planning personnel away from the alliance.

This potential shakeup in the EU’s second-wealthiest country also comes as Washington and Brussels are trying to intensify the sanction campaign against Russia. Macron, for his part, has called for fresh sanctions targeting Russian oil and gas imports. But would a President Le Pen, a long-time Putin sycophant, refuse to implement these sanctions? Would she try to undo existing sanctions? Will she cease France's military aid to Ukraine?

Given Le Pen’s insistence that France must resume its alliance with Moscow, it’s fair to assume that the answer to at least some of these questions is “yes.”