ask ian

Trump, Xi, and the new US–China standoff

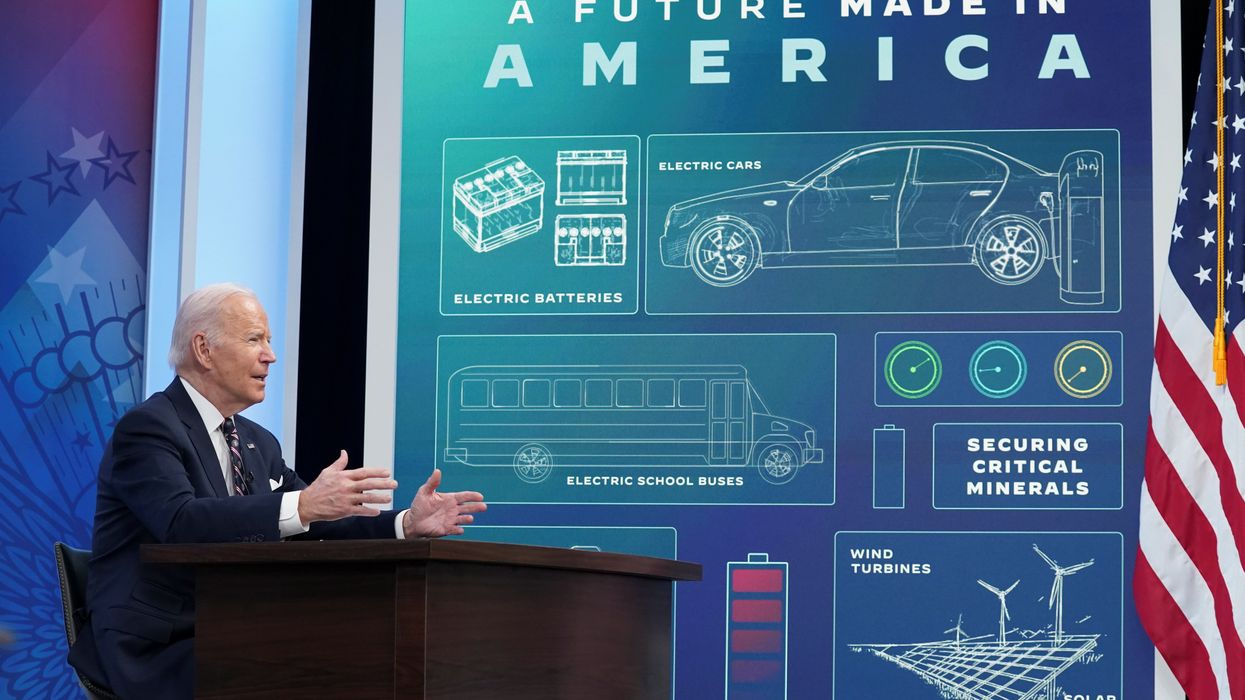

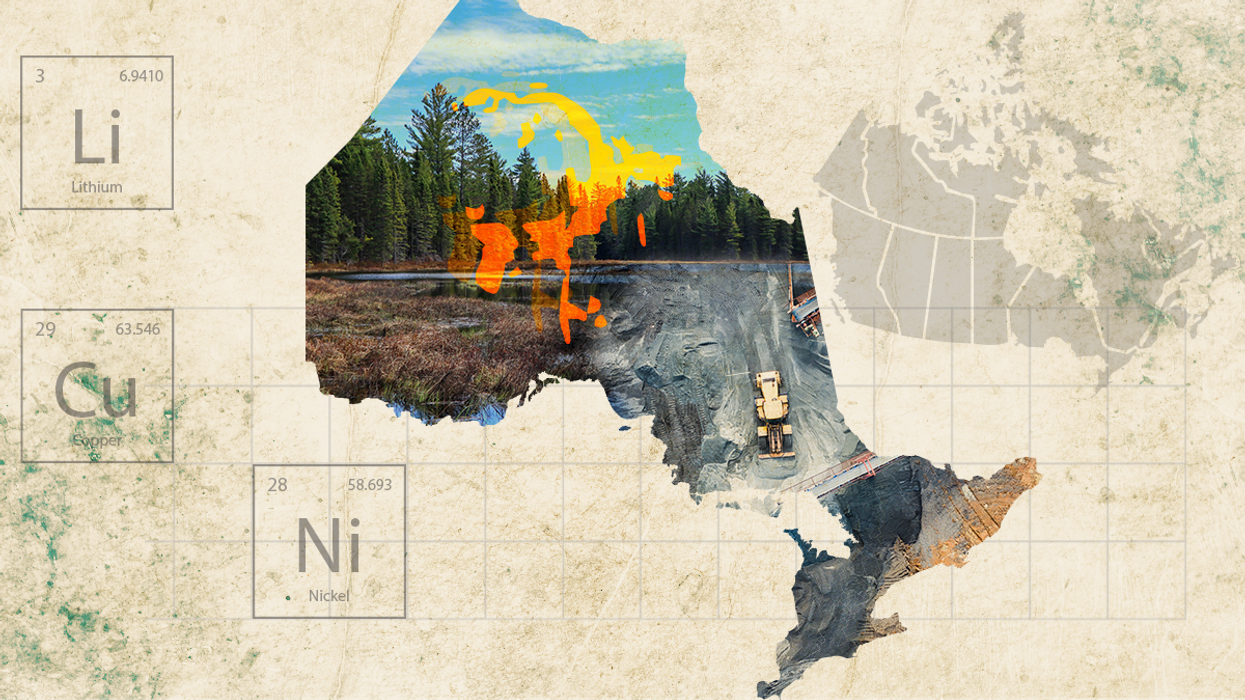

In Ask Ian, Ian Bremmer notes that US–China relations are once again on edge. After Washington expanded export controls on Chinese tech firms, Beijing struck back with new limits on critical minerals. President Trump responded by threatening 100% tariffs, then quickly walked them back.

Oct 14, 2025