Asia

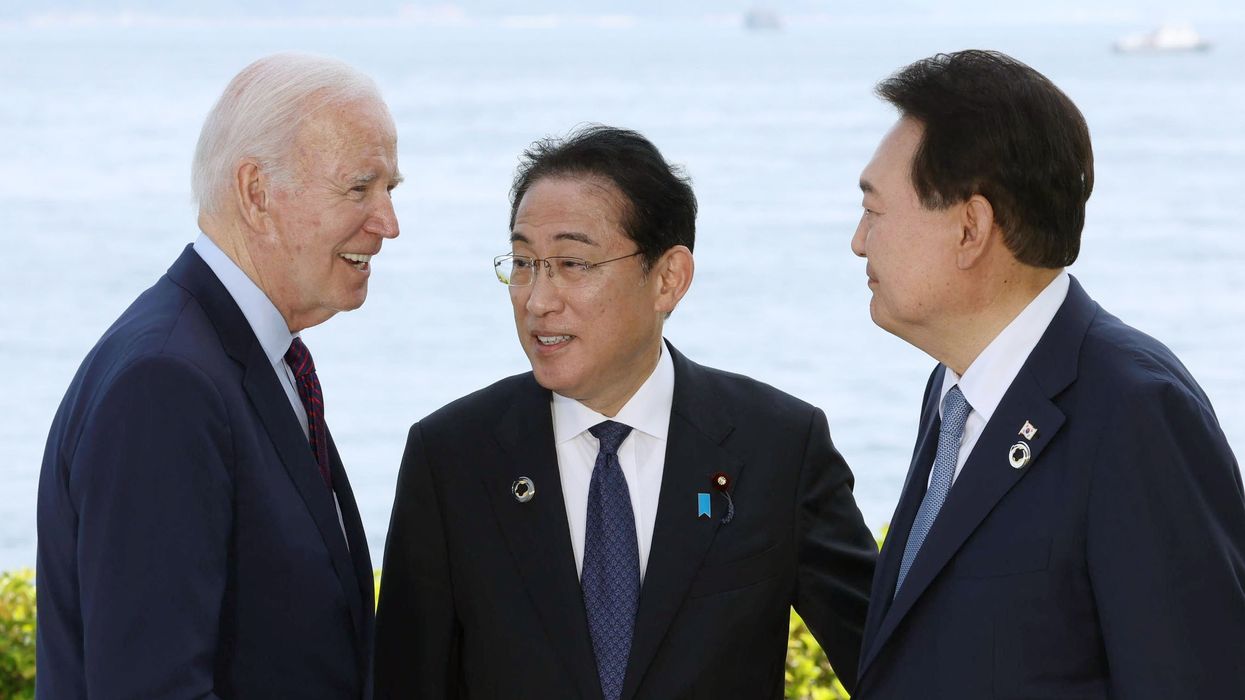

Biden brings South Korea and Japan together

On Friday, President Joe Biden will host South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida for a summit at the famous Camp David. While it might not seem like a big deal for Washington to facilitate a summit with America’s two closest Asian partners, it is monumental that South Korea, in particular, appears ready and willing to enlist in a new US-led trilateral alliance with Japan.

Aug 17, 2023