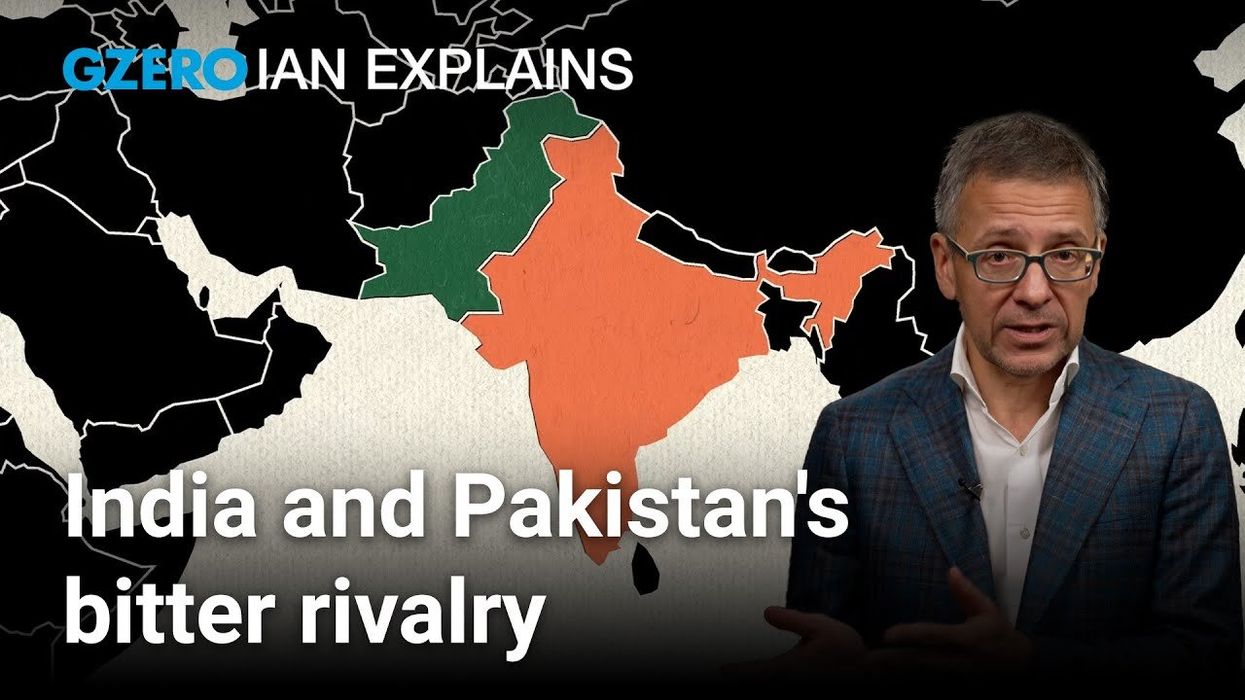

GZERO World with Ian Bremmer

India vs. Pakistan: Rising tensions in South Asia

Following a terrorist attack in Kashmir last spring, India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers, exchanged military strikes in an alarming escalation. Former Pakistani Foreign Minister Hina Khar joins Ian Bremmer on GZERO World to discuss Pakistan’s perspective in the simmering conflict.

Aug 16, 2025