What We're Watching

Noboa wins, but Correa remains at heart of Ecuador’s political crisis

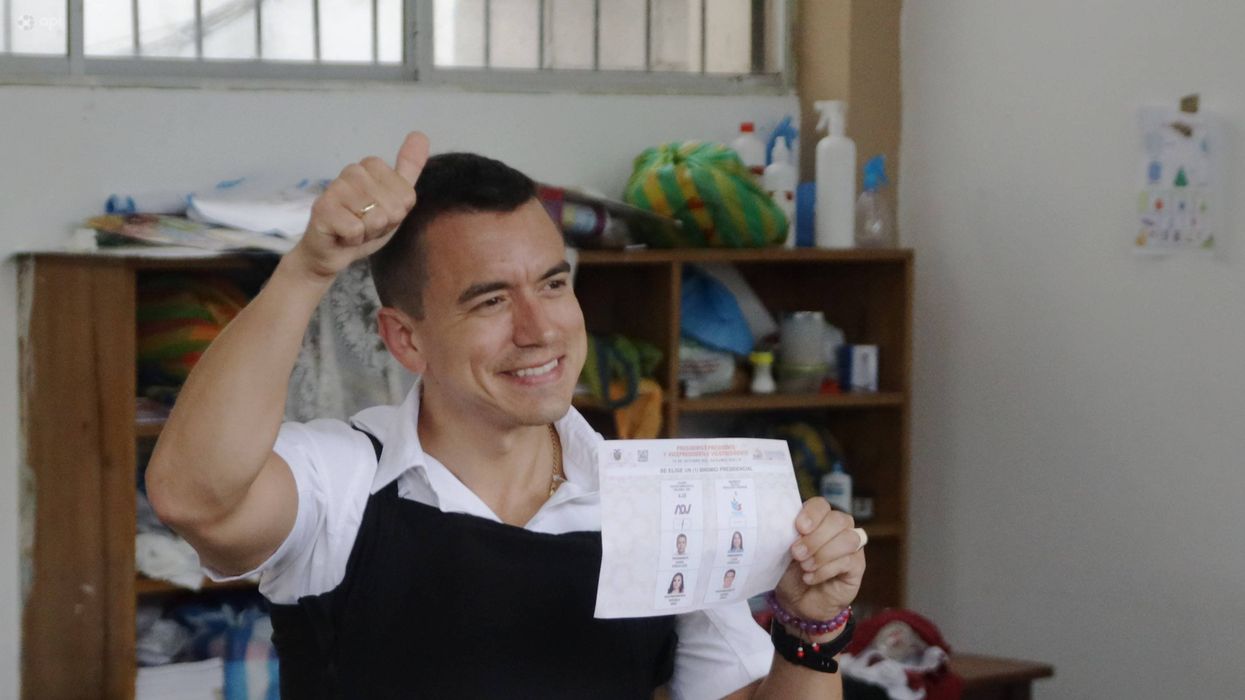

On Sunday, Ecuadorians elected their youngest-ever president, businessman Daniel Noboa, amid deep political rifts that exacerbate a growing security crisis in the small Andean nation.

Oct 16, 2023