News

In 1989, China Chose a Future That We Are Now Living In

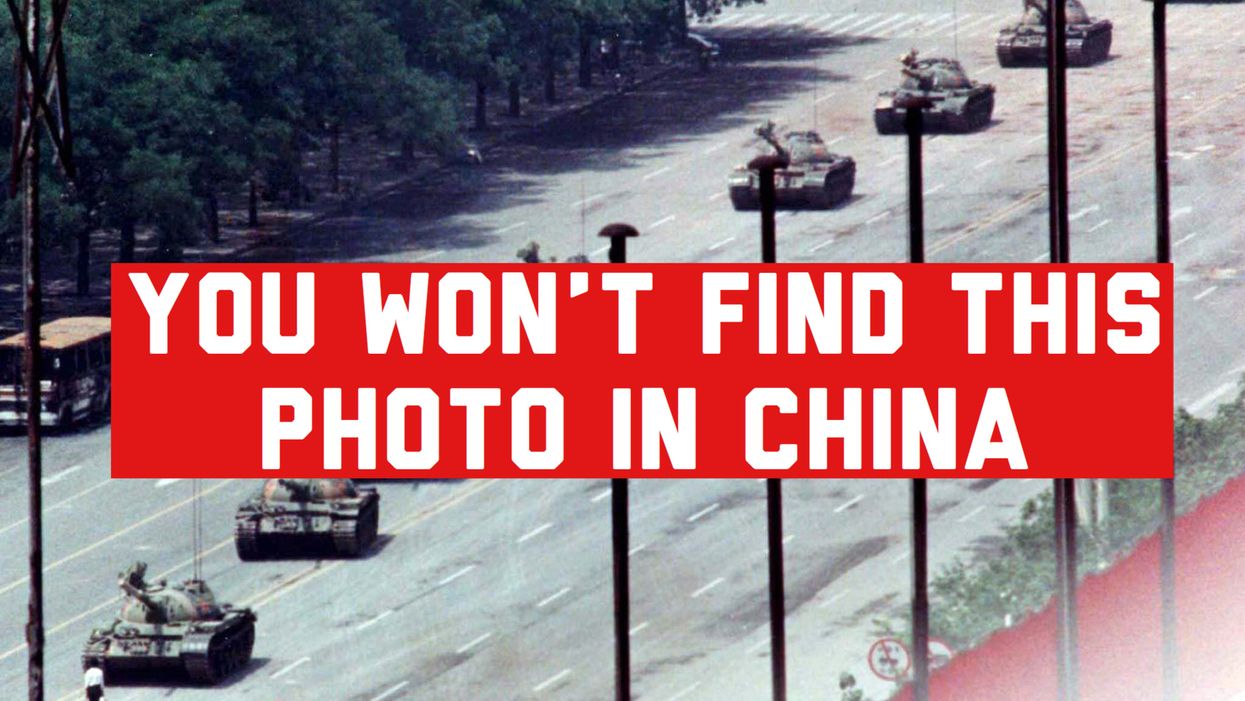

Thirty years ago today, the Chinese government ordered soldiers to open fire on students and blue-collar workers who had taken over Tiananmen square in central Beijing to demand more political freedom and less corruption. Nobody knows how many people were killed, but estimates run into the thousands.

Jun 03, 2019