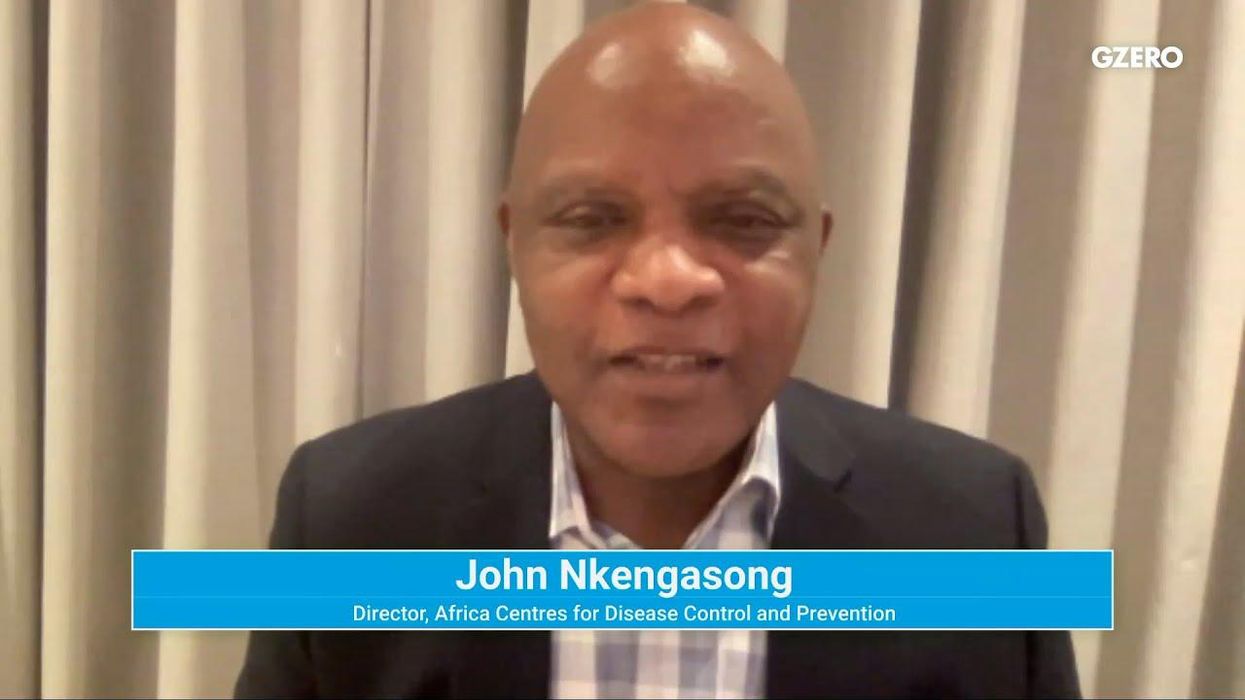

Africa still sees COVID glass half empty — African CDC chief

Is the pandemic over? Depends on where you are, according to Dr. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "If you are sitting in Africa, they have the glasses half empty. And if you are sitting in the global note, the glass might be half full," he said during a livestream discussion on equitable vaccine distribution hosted by GZERO Media in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Nkengasong explained that the optimism seen now in countries like the US or the UK, where so many people have been vaccinated, is "not exactly what we are seeing in the part of the world that I'm serving." Africans are still very worried about COVID, he said. Across the continent, the pandemic is still seen as unpredictable, and its trajectory remains uncertain.