July 24, 2024

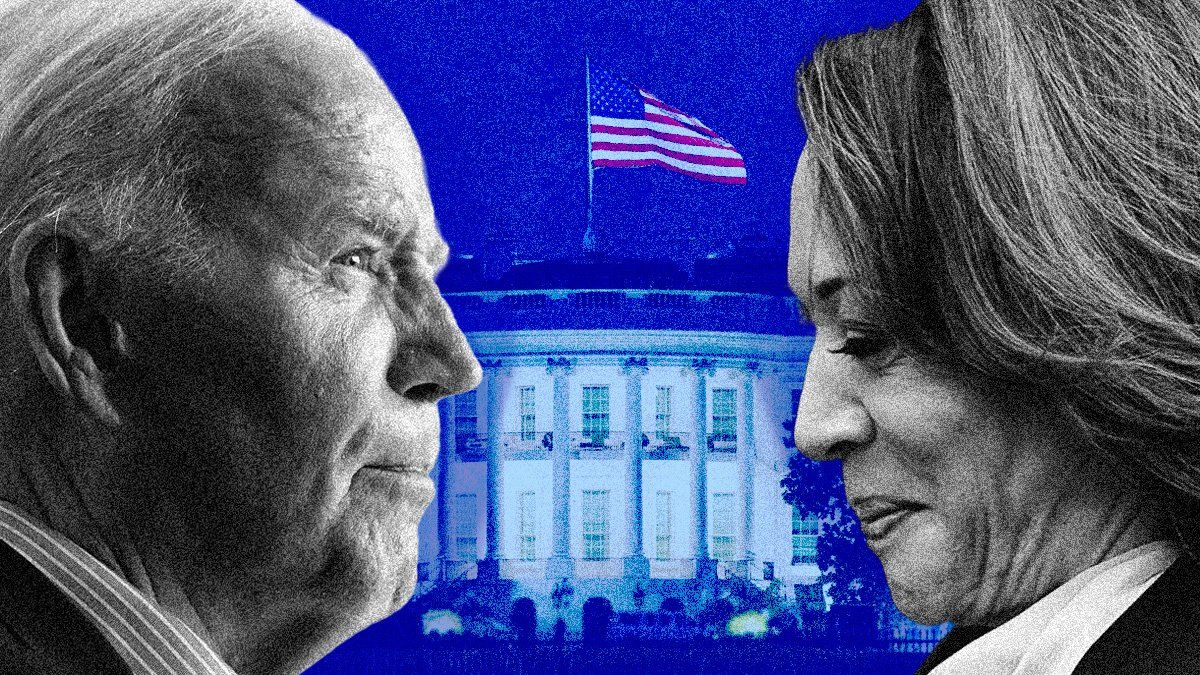

I have little doubt that President Joe Biden’s belated but essential decision to bow out of the 2024 presidential election on Sunday will go down in history as a patriotic act.

Following his infamous debate performance on June 27, an overwhelming majority of Americans – including two-thirds of Democrats – came to the conclusion that the president was no longer physically and mentally fit to serve another four-year term in office. As things stood last Saturday, Donald Trump – fresh off a failed assassination attempt and a triumphant Republican convention – looked set to retake the White House and likely control both houses of Congress, with little an ailing Biden could do to turn things around.

By finally agreeing to step down when his term ends in January, Biden jolted the race 100 days out and gave his party a fighting chance to protect the country – and the world – from what he sees as the existential threat of an unrestrained Trump. Only he had the power to do that, and when push came to shove (and there was plenty of shoving), he met the moment. It was a fitting capstone to a lifetime of public service.

This is what leadership looks like. Contrary to what many are claiming, there was nothing inevitable about Biden’s decision to withdraw. Yes, he was under immense pressure from his party and the media to step down. Yes, all evidence pointed toward near-certain disaster in November if he stayed on. Yes, his legacy was on the line. And yet … he still had a choice. His exit was not preordained. No one forced his hand – in fact, no one could force his hand. It was entirely up to Joe Biden, and Joe Biden alone, to do the right thing. This couldn’t have been easy – if it was, everyone would do it. And we know for a fact that not everyone would’ve made the same choice – least of all Trump, a man who is constitutionally incapable of putting party and country above himself.

Did Biden come to his decision reluctantly, and only after weeks spent in anger and denial? No doubt. It’s hard enough for anyone to voluntarily give up power, but it’s even harder for a person with Biden’s life history who’s also coming to terms with his own mortality. Should he have withdrawn much sooner? Absolutely – I never thought he should have run for reelection in the first place, and I said so publicly many times. Will this delay end up costing Democrats the election? It’s possible, though we may never know.

But we shouldn’t forget the “better” in “better late than never.” What matters most is that he finally got there. Biden could’ve held on until the bitter end, consequences be damned. Instead, he chose to put America first. It was a decision worthy of a leader. Not a winner, but a leader. He deserves credit for it – as does the Democratic Party, which has shown itself to be a much healthier and more functional institution than anyone thought. Can anyone seriously imagine today’s GOP launching a coordinated pressure campaign to depose Trump, even though so many Republicans privately criticize him as unfit and believe him to be an electoral drag?

It gives me a little hope in a country where politicians don’t often do the right thing, and where political parties all too easily bend to the will of their leaders even when it becomes clear they serve only themselves.

Harris or bust. Shortly after announcing his withdrawal, Biden endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris for the nomination. The entire Democratic establishment – with the notable exception of Barack Obama – quickly followed suit and rallied behind her. Within 24 hours, Harris had been endorsed by every viable potential challenger as well as an overwhelming majority of Democratic governors, members of Congress, and state party chairs. By Monday evening, her campaign had raised $150 million from major donors and $81 million from small donors, and she had secured more than enough pledged delegates to become the party’s presumptive nominee.

Although an ostensibly competitive and democratically legitimate nomination process would have ultimately benefitted Democrats by ensuring the winner had what it takes to take on Trump and appeal to a broad swath of voters, the speed with which the party coalesced around Harris ensures next month’s convention in Chicago will be little more than a coronation ceremony. With only 54 delegates currently undecided and a minimum of 300 needed for any would-be nominee to compete, it’s impossible to imagine a challenger not named Marianne Williamson or Dean Phillips emerging.

And that’s … not a disaster for the Democrats. Harris may not have been the best possible candidate Democrats could’ve put forward a year (or four) ago, but she was the most viable candidate to replace Biden, unite the party, and avoid a down-ballot bloodbath at this late stage.

What can be, unburdened by what has been? The question now is not whether there was a better Democratic candidate than Harris, but whether Harris can beat Trump. And on that front, the jury is still out. We simply don’t have enough recent polling data on this matchup yet to get a decent idea of where things stand today.

Here’s what we do know: This is an incredibly tough environment for an incumbent’s successor, with a majority of voters telling pollsters they are unhappy with the state of the country. And Harris is no Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, or Ronald Reagan – a generational talent with the charisma and vision to work political miracles. So she starts as the underdog accordingly. But off the bat, she has dramatically better odds than Biden because she solves the president’s biggest electability challenge: his age. And she has more upside than Trump, who remains a historically unpopular candidate with a hard ceiling of 45% of national support. By contrast, nearly 10% of Americans don’t even have an opinion of her yet, so she has room to define herself.

Can Harris break above Trump’s ceiling? She’s neither a proven national candidate nor a distinguished campaigner, having fizzled out before reaching the Iowa caucus during the 2020 presidential primaries. She has plenty of weaknesses for Republicans to exploit, including unpopular Biden administration policies (notably on the border) for which voters may blame her. And there’s a chance she could lose more older, white, and moderate working-class voters relative to Biden than she picks up young, nonwhite, and progressive ones.

But at 59, Harris is able to string together full sentences, give cogent stump speeches, campaign vigorously, and effectively deliver the abortion and democracy messages that worked well for Democrats in 2022. She can also play offense on Trump’s age – he’s 78 – and mental fitness, now an exclusively Republican liability that 50% of all voters found disqualifying in the former president nary a week ago.

How this will all net out in November, no one knows yet. Think about all that’s happened in the last two weeks, and imagine all that could change in the next 100 days. That’s an eternity in US politics – certainly longer than entire general election campaigns normally take in most other democracies.

All we can say for sure is Biden has given the Democrats a fighting chance and made the election both more competitive and more uncertain than it was a week ago.

More For You

How is the US is reshaping global power dynamics, using tariffs and unilateral action to challenge the international order it once led? Michael Froman joins Ian Bremmer on GZERO World to discuss.

Most Popular

- YouTube

In this Quick Take from Munich, Ian Bremmer examines the state of the transatlantic alliance as the 62nd Munich Security Conference concludes.

- YouTube

At the 2026 Munich Security Conference, Brad Smith announces the launch of the Trusted Tech Alliance, a coalition of global technology leaders, including Microsoft, committing to secure cross-border tech flows, ethical governance, and stronger data protections.

When the US shift from defending the postwar rules-based order to challenging it, what kind of global system emerges? CFR President Michael Froman joins Ian Bremmer on the GZERO World Podcast to discuss the global order under Trump's second term.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.